9 Multiobjective Optimization

Up to this point in the book, all of our optimization problem formulations have had a single objective function. In this chapter, we consider multiobjective optimization problems, that is, problems whose formulations have more than one objective function. Some common examples of multiobjective optimization include risk versus reward, profit versus environmental impact, acquisition cost versus operating cost, and drag versus noise.

9.1 Multiple Objectives¶

Before discussing how to solve multiobjective problems, we must first explore what it means to have more than one objective. In some sense, there is no such thing as a multiobjective optimization problem. Although many metrics are important to the engineer, only one thing can be made best at a time. A common technique when presented with multiple objectives is to assign weights to the various objectives and combine them into a single objective.

More generally, multiobjective optimization helps explore the trade-offs between different metrics. Still, if we select one design from the presented options, we have indirectly chosen a single objective. However, the corresponding objective function may be difficult to formulate beforehand.

Despite these considerations, there are still good reasons to pursue a multiobjective problem. A few of the most common reasons are as follows:

Multiobjective optimization can quantify the trade-off between different objectives. The benefits of this approach will become apparent when we discuss Pareto surfaces and can lead to important design insights.

Multiobjective optimization provides a “family” of designs rather than a single design. A family of options is desirable when decision-making needs to be deferred to a later stage as more information is gathered. For example, an executive team or higher-fidelity numerical simulations may be used to make later design decisions.

For some problems, the underlying objective is either unknown or too difficult to compute. For example, cost and environmental impact may be two important metrics for a new design. Although the latter could arguably be turned into a cost, doing so may be too difficult to quantify and add an unacceptable amount of uncertainty (see Chapter 12).

Mathematically, the only change to our optimization problem formulation is that the objective statement,

becomes

The constraints are unchanged unless some of them have been reformulated as objectives. This multiobjective formulation might require trade-offs when trying to minimize all functions simultaneously because, beyond some point, further reduction in one objective can only be achieved by increasing one or more of the other objectives.

One exception occurs if the objectives are independent because they depend on different sets of design variables. Then, the objectives are said to be separable, and they can be minimized independently. If there are constraints, these need to be separable as well. However, separable objectives and constraints are rare because functions tend to be linked in engineering systems.

Given that multiobjective optimization requires trade-offs, we need a new definition of optimality. In the next section, we explain how there is an infinite number of optimal points, forming a surface in the space of objective functions. After defining optimality for multiple objectives, we present several possible methods for solving multiobjective optimization problems.

9.2 Pareto Optimality¶

With multiple objectives, we have to reconsider what it means for a point to be optimal. In multiobjective optimization, we use the concept of Pareto optimality.

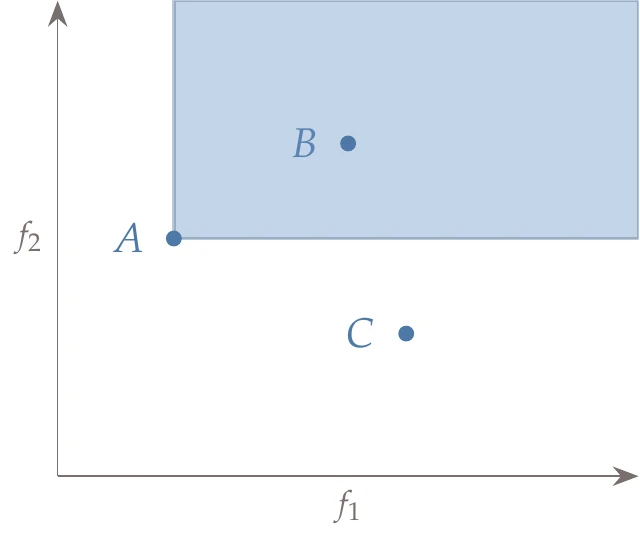

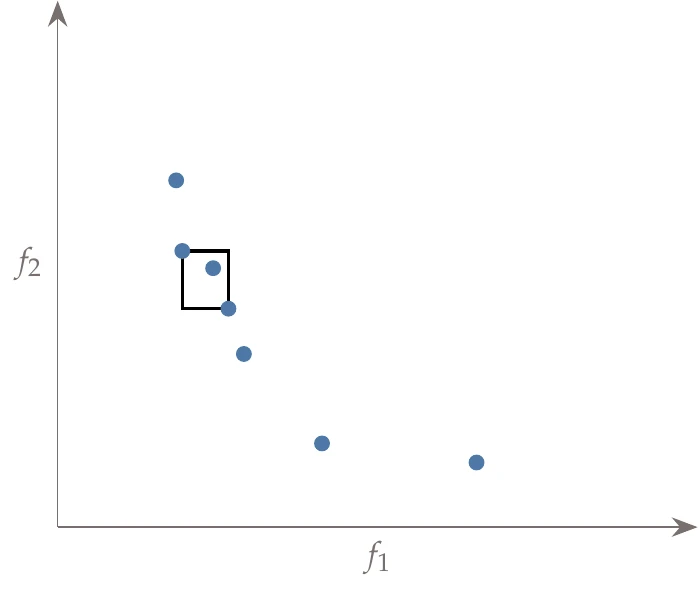

Figure 9.1:Three designs, , , and , are plotted against two objectives, and . The region in the shaded rectangle highlights points that are dominated by design .

Figure 9.1 shows three designs measured against two objectives that we want to minimize: and . Let us first compare design A with design B. From the figure, we see that design A is better than design B in both objectives. In the language of multiobjective optimization, we say that design A dominates design B. One design is said to dominate another design if it is superior in all objectives (design A dominates any design in the shaded rectangle). Comparing design A with design C, we note that design A is better in one objective () but worse in the other objective (). Neither design dominates the other.

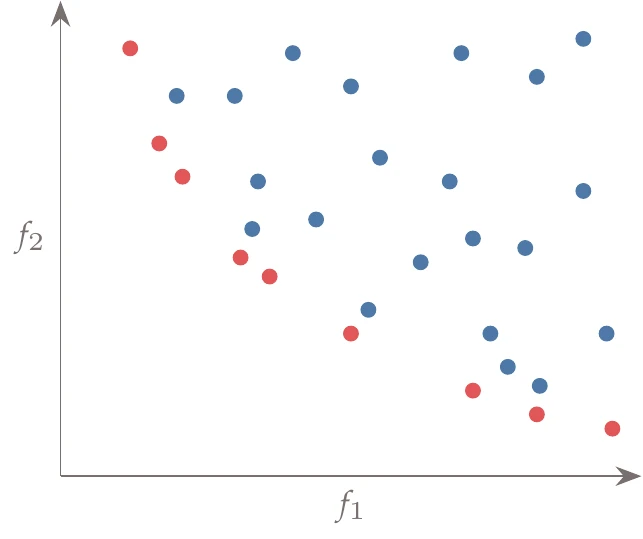

Figure 9.2:A plot of all the evaluated points in the design space plotted against two objectives, and . The set of red points is not dominated by any other and is thus the current approximation of the Pareto set.

A point is said to be nondominated if none of the other evaluated points dominate it (Figure 9.2). If a point is nondominated by any point in the entire domain, then that point is called Pareto optimal. This does not imply that this point dominates all other points; it simply means no other point dominates it. The set of all Pareto optimal points is called the Pareto set. The Pareto set refers to the vector of points , whereas the Pareto front refers to the vector of functions .

9.3 Solution Methods¶

Various solution methods exist for solving multiobjective problems. This chapter does not cover all methods but highlights some of the more commonly used approaches. These include the weighted-sum method, the epsilon-constraint method, the normal boundary intersection (NBI) method, and evolutionary algorithms.

9.3.1 Weighted Sum¶

The weighted-sum method is easy to use, but it is not particularly efficient. Other methods exist that are just as simple but have better performance. It is only introduced because it is well known and is frequently used. The idea is to combine all of the objectives into one objective using a weighted sum, which can be written as

where is the number of objectives, and the weights are usually normalized such that

If we have two objectives, the objective reduces to

where is a weight in .

Consider a two-objective case. Points on the Pareto set are determined by choosing a weight , completing the optimization for the composite objective, and then repeating the process for a new value of . It is straightforward to see that at the extremes and , the optimization returns the designs that optimize one objective while ignoring the other. The weighted-sum objective forms an equation for a line with the objectives as the ordinates.

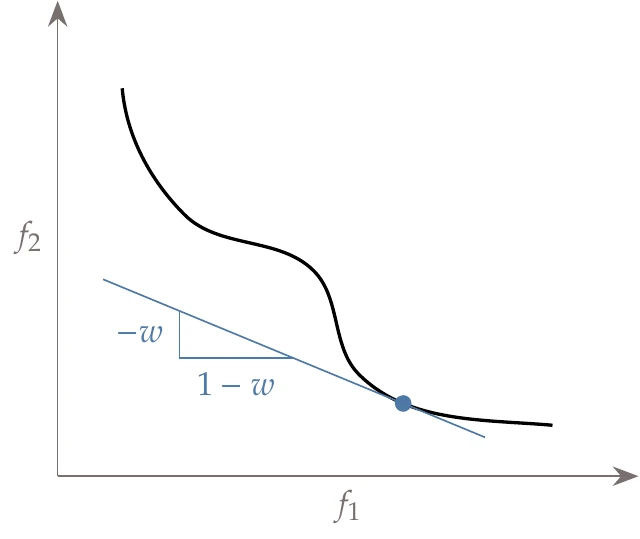

Figure 9.4:The weighted-sum method defines a line for each value of and finds the point tangent to the Pareto front.

Conceptually, we can think of this method as choosing a slope for the line (by selecting ), then pushing that line down and to the left as far as possible until it is just tangent to the Pareto front (Figure 9.4). With this form of the objective, the slope of the line would be

This procedure identifies one point in the Pareto set, and the procedure must then be repeated with a new slope.

The main benefit of this method is that it is easy to use.

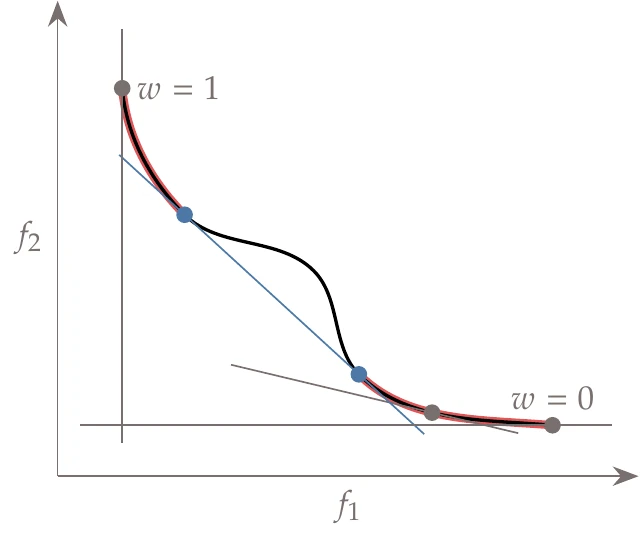

Figure 9.5:The convex portions of this Pareto front are the portions highlighted.

However, the drawbacks are that (1) uniform spacing in leads to nonuniform spacing along with the Pareto set, (2) it is not apparent which values of should be used to sweep out the Pareto set evenly, and (3) this method can only return points on the convex portion of the Pareto front.

In Figure 9.5, we highlight the convex portions of the Pareto front from Figure 9.4. If we utilize the concept of pushing a line down and to the left, we see that these are the only portions of the Pareto front that can be found using a weighted-sum method.

9.3.2 Epsilon-Constraint Method¶

The epsilon-constraint method works by minimizing one objective while setting all other objectives as additional constraints:1

Then, we must repeat this procedure for different values of .

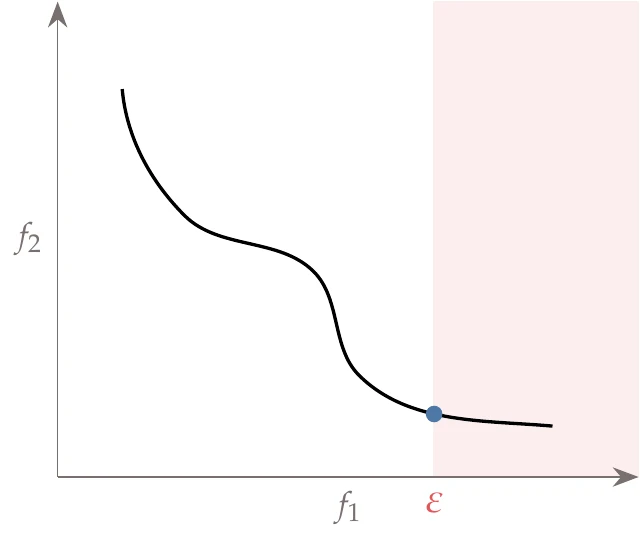

This method is visualized in Figure 9.6. In this example, we constrain to be less than or equal to a certain value and minimize to find the corresponding point on the Pareto front. We then repeat this procedure for different values of .

Figure 9.6:The vertical line represents an upper bound constraint on . The other objective, , is minimized to reveal one point in the Pareto set. This procedure is then repeated for different constraints on to sweep out the Pareto set.

One advantage of this method is that the values of correspond directly to the magnitude of one of the objectives, so determining appropriate values for is more intuitive than selecting the weights in the previous method. However, we must be careful to choose values that result in a feasible problem. Another advantage is that this method reveals the nonconvex portions of the Pareto front. Both of these reasons strongly favor using the epsilon-constraint method over the weighted-sum method, especially because this method is not much harder to use. Its main limitation is that, like the weighted-sum method, a uniform spacing in does not generally yield a uniform spacing of the Pareto front (though it is usually much better spaced than weighted-sum), and therefore it might still be inefficient, particularly with more than two objectives.

9.3.3 Normal Boundary Intersection¶

The NBI method is designed to address the issue of nonuniform spacing along the Pareto front.2 We first find the extremes of the Pareto set; in other words, we minimize the objectives one at a time. These extreme points are referred to as anchor points. Next, we construct a plane that passes through the anchor points. We space points along this plane (usually evenly) and, starting from those points, solve optimization problems that search along directions normal to this plane.

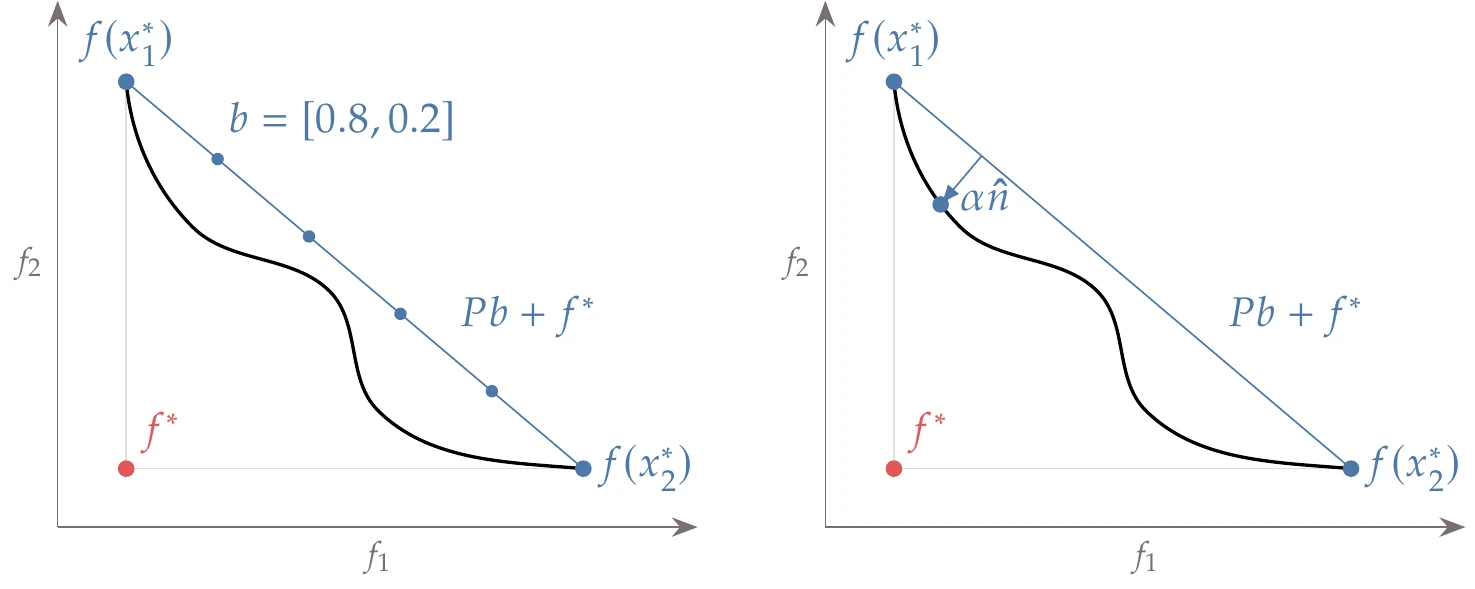

This procedure is shown in Figure 9.7 for a two-objective case. In this case, the plane that passes through the anchor points is a line. We now space points along this line by choosing a vector of weights , as illustrated on the left-hand of Figure 9.7. The weights are constrained such that , and . If we make and all other entries zero, then this equation returns one of the anchor points, . For two objectives, we would set and vary in equal steps between 0 and 1.

Figure 9.7:A notional example of the NBI method. A plane is created that passes through the single-objective optima (the anchor points), and solutions are sought normal to that plane for a more evenly spaced Pareto front.

Starting with a specific value of , we search along a direction perpendicular to the line defined by the anchor points, represented by in Figure 9.7 (right). We seek to find the point along this direction that is the farthest away from the anchor points line (a maximization problem), with the constraint that the point is consistent with the objective functions. The resulting optimal point found along this direction is a point on the Pareto front. We then repeat this process for another set of weighting parameters in .

We can see how this method is similar to the epsilon-constraint method, but instead of searching along lines parallel to one of the axes, we search along lines perpendicular to the plane defined by the anchor points. The idea is that even spacing along this plane is more likely to lead to even spacing along the Pareto front.

Mathematically, we start by determining the anchor points, which are just single-objective optimization problems. From the anchor points, we define what is called the utopia point. The utopia point is an ideal point that cannot be obtained, where every objective reaches its minimum simultaneously (shown in the lower-left corner of Figure 9.7):

where denotes the design variables that minimize objective . The utopia point defines the equation of a plane that passes through all anchor points,

where the column of is . A single vector , whose length is given by the number of objectives, defines a point on the plane.

We now define a vector () that is normal to this plane, in the direction toward the origin. We search along this vector using a step length , while maintaining consistency with our objective functions yielding

Computing the exact normal () is involved, and the vector does not need to be exactly normal. As long as the vector points toward the Pareto front, then it will still yield well-spaced points. In practice, a quasi-normal vector is often used, such as,

where is a vector of 1s.

We now solve the following optimization problem, for a given vector , to yield a point on the Pareto front:

This means that we find the point farthest away from the anchor-point plane, starting from a given value for , while satisfying the original problem constraints. The process is then repeated for additional values of to sweep out the Pareto front.

In contrast to the previously mentioned methods, this method yields a more uniformly spaced Pareto front, which is desirable for computational efficiency, albeit at the cost of a more complex methodology.

For most multiobjective design problems, additional complexity beyond the NBI method is unnecessary. However, even this method can still have deficiencies for problems with unusual Pareto fronts, and new methods continue to be developed. For example, the normal constraint method uses a very similar approach,3 but with inequality constraints to address a deficiency in the NBI method that occurs when the normal line does not cross the Pareto front. This methodology has undergone various improvements, including better scaling through normalization.4 A more recent improvement performs an even more efficient generation of the Pareto frontier by avoiding regions of the Pareto front where minimal trade-offs occur.5

9.3.4 Evolutionary Algorithms¶

Gradient-free methods can, and occasionally do, use all of the previously described methods. However, evolutionary algorithms also enable a fundamentally different approach. Genetic algorithms (GAs), a specific type of evolutionary algorithm, were introduced in Section 7.6.[1]

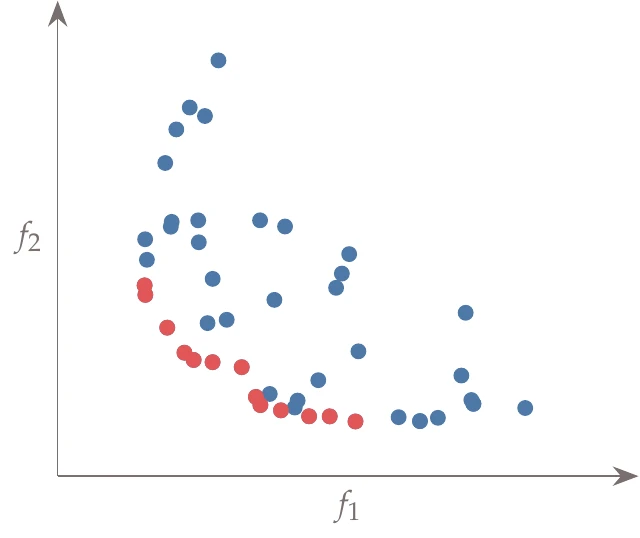

A GA is amenable to an extension that can handle multiple objectives because it keeps track of a large population of designs at each iteration. If we plot two objective functions for a given population of a GA iteration, we get something like that shown in Figure 9.9. The points represent the current population, and the highlighted points in the lower left are the current nondominated set.

Figure 9.9:Population for a multiobjective GA iteration plotted against two objectives. The nondominated set is highlighted at the bottom left and eventually converges toward the Pareto front.

As the optimization progresses, the nondominated set moves further down and to the left and eventually converges toward the actual Pareto front.

In the multiobjective version of the GA, the reproduction and mutation phases are unchanged from the single-objective version. The primary difference is in determining the fitness and the selection procedure. Here, we provide an overview of one popular approach, the elitist nondominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II).[2]

A step in the algorithm is to find a nondominated set (i.e., the current approximation of the Pareto set), and several algorithms exist to accomplish this. In the following, we use the algorithm by Kung et al.,9 which is one of the fastest. This procedure is described in Algorithm 9.1, where “front” is a shorthand for the nondominated set (which is just the current approximation of the Pareto front). The algorithm recursively divides the population in half and finds the nondominated set for each half separately.

Before calling the algorithm, the population should be sorted by the first objective. First, we split the population into two halves, where the top half is superior to the bottom half in the first objective. Both populations are recursively fed back through the algorithm to find their nondominated sets. We then initialize a merged population with the members of the top half. All members in the bottom half are checked, and any that are nondominated by any member of the top half are added to the merged population. Finally, we return the merged population as the nondominated set.

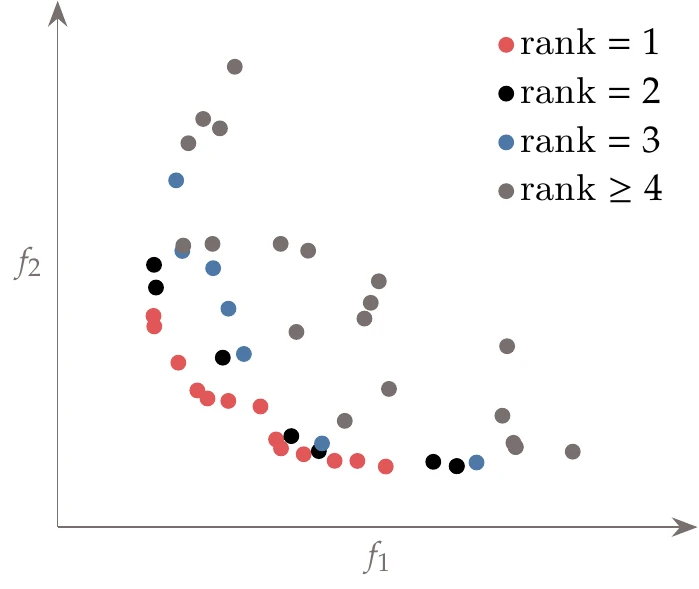

With NSGA-II, in addition to determining the nondominated set, we want to rank all members by their dominance depth, which is also called nondominated sorting. In this approach, all nondominated points in the population (i.e., the current approximation of the Pareto set) are given a rank of 1. Those points are then removed from the set, and the next set of nondominated points is given a rank of 2, and so on.

Figure 9.10:Points in the population highlighted by rank.

Figure 9.10 shows a sample population and illustrates the positions of the points with various rank values. There are alternative procedures that perform nondominated sorting directly, but we do not detail them here. This algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 9.2.

The new population in the GA is filled by placing all rank 1 points in the new population, then all rank 2 points, and so on. At some point, an entire group of constant rank will not fit within the new population. Points with the same rank are all equivalent as far as Pareto optimality is concerned, so an additional sorting mechanism is needed to determine which members of this group to include.

Inputs:

: A population

Outputs:

rank: The rank for each member in the population

Initialize current rank

Set subpopulation as entire population

while length() > 0 do

= front(sort()) Identify the current front

Set rank for every member of to

Remove all members of from

Increment rank

end while

We perform selection within a group that can only partially fit to preserve diversity. Points in this last group are ordered by their crowding distance, which is a measure of how spread apart the points are. The algorithm seeks to preserve points that are well spread. For each point, a hypercube in objective space is formed around it, which, in NSGA-II, is referred to as a cuboid.

Figure 9.11:A cuboid around one point, demonstrating the definition of crowding distance (except that the distances are normalized).

Figure 9.11 shows an example cuboid considering the rank 3 points from Figure 9.10. The hypercube extends to the function values of its nearest neighbors in the function space. That does not mean that it necessarily touches its neighbors because the two closest neighbors can differ for each objective. The sum of the dimensions of this hypercube is the crowding distance.

When summing the dimensions, each dimension is normalized by the maximum range of that objective value. For example, considering only for the moment, if the objectives were in ascending order, then the contribution of point to the crowding distance would be

where is the size of the population. Sometimes, instead of using the first and last points in the current objective set, user-supplied values are used for the min and max values of that appear in that denominator. The anchor points (the single-objective optima) are assigned a crowding distance of infinity because we want to preference their inclusion. The algorithm for crowding distance is shown in Algorithm 9.3.

Inputs:

: A population

Outputs:

: Crowding distances

Initialize with zeros

for to number of objectives do

Set as a vector containing the objective for each member in

and let contain the corresponding indices ()

Anchor points receive an infinite crowding distance

for to do

Add distance for interior pointsend for

end for

We can now put together the overall multiobjective GA, as shown in Algorithm 9.4, where we use the components previously described (nondominated set, nondominated sorting, and crowding distance).

Inputs:

: Variable upper bounds

: Variable lower bounds

Outputs:

: Best point

Generate initial population

while Stopping criterion is not satisfied do

Using a parent population , proceed as a standard GA for selection, crossover, and mutation, but use a crowded tournament selection to produced an offspring population

Combine populations

Compute for of using Algorithm 9.2

Fill new parent population with as many whole ranks as possible

while true do

set as all with

if length() + length() > then

break

end if

add to

end while

For last rank that does not fit, add by crowding distance

if length() then

Population is not fulld = crowding() Algorithm 9.3, using last from terminated previous loop

Determine how many members to add

Sort by the crowding distance in descending order

Add the first entries from to

end if

end while

The crossover and mutation operations remain the same. Tournament selection (Figure 7.25) is modified slightly to use this algorithm’s ranking and crowding metrics. In the tournament, a member with a lower rank is superior. If two members have the same rank, then the one with the larger crowding distance is selected. This procedure is called crowded tournament selection.

After reproduction and mutation, instead of replacing the parent generation with the offspring generation, both the parent generation and the offspring generation are saved as candidates for the next generation. This strategy is called elitism, which means that the best member in the population is guaranteed to survive.

The population size is now twice its original size (), and the selection process must reduce the population back down to size . This is done using the procedure explained previously. The new population is filled by including all rank 1 members, rank 2 members, and so on until an entire rank can no longer fit. Inclusion for members of that last rank is done in the order of the largest crowding distance until the population is filled.

Many variations are possible, so although the algorithm is based on the concepts of NSGA-II, the details may differ somewhat.

The main advantage of this multiobjective approach is that if an evolutionary algorithm is appropriate for solving a given single-objective problem, then the extra information needed for a multiobjective problem is already there, and solving the multiobjective problem does not incur much additional computational cost. The pros and cons of this approach compared to the previous approaches are the same as those of gradient-based versus gradient-free methods, except that the multiobjective gradient-based approaches require solving multiple problems to generate the Pareto front. Still, solving multiple gradient-based problems may be more efficient than solving one gradient-free problem, especially for problems with a large number of design variables.

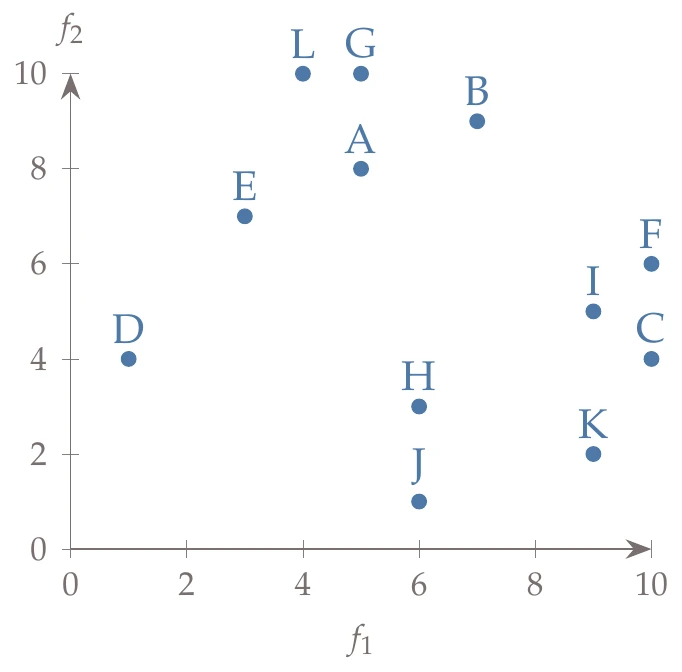

After reproduction and mutation, we are left with a combined population of parents and offspring. In this small example, the combined population is of size 12, so we must reduce it back to 6. This example has two objectives, and the values for each member in the population are shown in the following table, where we assign a letter to each member. The population is plotted in Figure 9.12.

Figure 9.12:Population for this example.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | |

| 5 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 4 | |

| 8 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

First, we compute the ranks using Algorithm 9.2, resulting in the following output:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

We see that the current nondominated set consists of points D and J and that there are four different ranks.

Next, we start filling the new population in the order of rank. Our maximum capacity is 6, so all rank 1 {D, J} and rank 2 {E, H, K} fit. We cannot add rank 3 {A, C, I, L} because the population size would be 9. So far, our new population consists of {D, J, E, H, K}. To choose which items from rank 3 continue forward, we compute the crowding distance for the members of rank 3:

| A | C | I | L |

| 1.67 | 1.5 |

We would then add, in order {C, L, A, I}, but we only have room for one, so we add C and complete this iteration with a new population of {D, J, E, H, K, C}.

9.4 Summary¶

Multiobjective optimization is particularly useful in quantifying trade-off sensitivities between critical metrics. It is also useful when we seek a family of potential solutions rather than a single solution. Some scenarios where a family of solutions might be preferred include when the models used in optimization are low fidelity and higher-fidelity design tools will be applied or when more investigation is needed. A multiobjective approach can produce candidate solutions for later refinement.

The presence of multiple objectives changes what it means for a design to be optimal. A design is Pareto optimal when it is nondominated by any other design. The weighted-sum method is perhaps the most well-known approach, but it is not recommended because other methods are just as easy and much more efficient. The epsilon-constraint method is still simple yet almost always preferable to the weighted-sum method. It typically provides a better spaced Pareto front and can resolve any nonconvex portions of the front. If we are willing to use a more complex approach, the normal boundary intersection method is even more efficient at capturing a well-spaced Pareto front.

Some gradient-free methods, such as a multiobjective GA, can also generate Pareto fronts. If a gradient-free approach is a good fit in the single objective version of the problem, adding multiple objectives can be done with little extra cost. Although gradient-free methods are sometimes associated with multiobjective problems, gradient-based algorithms may be more effective for many multiobjective problems.

Problems¶

Answer true or false and justify your answer.

The solution of multiobjective optimization problems is usually an infinite number of points.

It is advisable to include as many objectives as you can in your problem formulation to make sure you get the best possible design.

Multiobjective optimization can quantify trade-offs between objectives and constraints.

If the objectives are separable, that means that they can be minimized independently and that there is no Pareto front.

A point dominates point if it is better than in at least one objective.

The Pareto set is the set of points that dominate all other points in the objective space.

When a point is Pareto optimal, you cannot make either of the objectives better.

The weighted-sum method obtains the Pareto front by solving optimization problems with different objective functions.

The epsilon-constraint method obtains the Pareto front by constraining one objective and minimizing all the others.

The utopia point is the point where every objective has a minimum value.

It is not possible to compute a Pareto front with a single-objective optimizer.

Because GAs optimize by evolving a population of diverse designs, they can be used for multiobjective optimization without modification.

Which of the following function value pairs would be Pareto optimal in a multiobjective minimization problem (there may be more than one)?

(20, 4)

(18, 5)

(34, 2)

(19, 6)

You seek to minimize the following two objectives:

Identify the Pareto front using the weighted-sum method with 11 evenly spaced weights: . If some parts of the front are underresolved, discuss how you might select weights for additional points.

Repeat Exercise 3 with the epsilon-constraint method. Constrain with 11 evenly spaced points between the anchor points. Contrast the Pareto front with that of the previous problem, and discuss whether improving the front with additional points will be easier with the previous method or with this method.

Repeat Exercise 3 with the normal boundary intersection method using the following 11 evenly spaced points:

Consider a two-objective population with the following combined parent/offspring population (objective values shown for all 16 members):

| 6.0 | 8.0 |

| 6.0 | 4.0 |

| 5.0 | 6.0 |

| 2.0 | 8.0 |

| 10.0 | 5.0 |

| 6.0 | 0.5 |

| 8.0 | 3.0 |

| 4.0 | 9.0 |

| 9.0 | 7.0 |

| 8.0 | 6.0 |

| 3.0 | 1.0 |

| 7.0 | 9.0 |

| 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 3.0 | 7.0 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 4.0 | 6.5 |

Develop code based on the NSGA-II procedure and determine the new population at the end of this iteration. Detail the results of each step during the process.

- Haimes, Y. Y., Lasdon, L. S., & Wismer, D. A. (1971). On a bicriterion formulation of the problems of integrated system identification and system optimization. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, SMC-1(3), 296–297. 10.1109/tsmc.1971.4308298

- Das, I., & Dennis, J. E. (1998). Normal-boundary intersection: A new method for generating the Pareto surface in nonlinear multicriteria optimization problems. SIAM Journal on Optimization, 8(3), 631–657. 10.1137/s1052623496307510

- Ismail-Yahaya, A., & Messac, A. (2002). Effective generation of the Pareto frontier using the normal constraint method. In Proceedings of the 40th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting & Exhibit. American Institute of Aeronautics. 10.2514/6.2002-178

- Messac, A., & Mattson, C. A. (2004). Normal constraint method with guarantee of even representation of complete Pareto frontier. AIAA Journal, 42(10), 2101–2111. 10.2514/1.8977

- Hancock, B. J., & Mattson, C. A. (2013). The smart normal constraint method for directly generating a smart Pareto set. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization, 48(4), 763–775. 10.1007/s00158-013-0925-6

- Schaffer, J. D. (1984). Some experiments in machine learning using vector evaluated genetic algorithms. [Phdthesis]. Vanderbilt University.

- Deb, K., Pratap, A., Agarwal, S., & Meyarivan, T. (2002). A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 6(2), 182–197. 10.1109/4235.996017

- Deb, K. (2008). Introduction to evolutionary multiobjective optimization. In Multiobjective Optimization (pp. 59–96). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-540-88908-3_3

- Kung, H. T., Luccio, F., & Preparata, F. P. (1975). On finding the maxima of a set of vectors. Journal of the ACM, 22(4), 469–476. 10.1145/321906.321910