6 Computing Derivatives

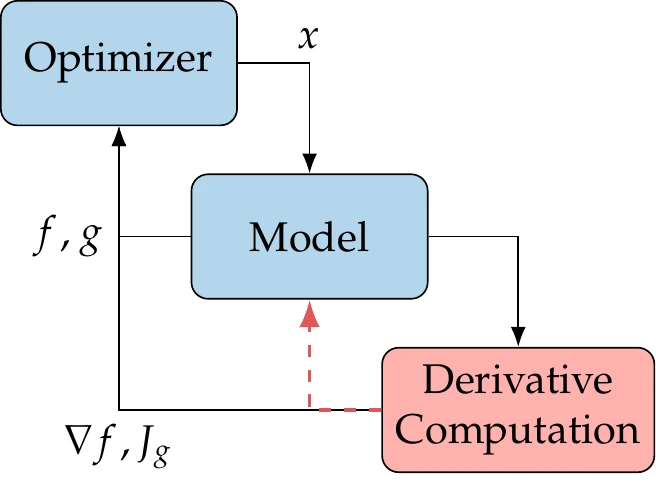

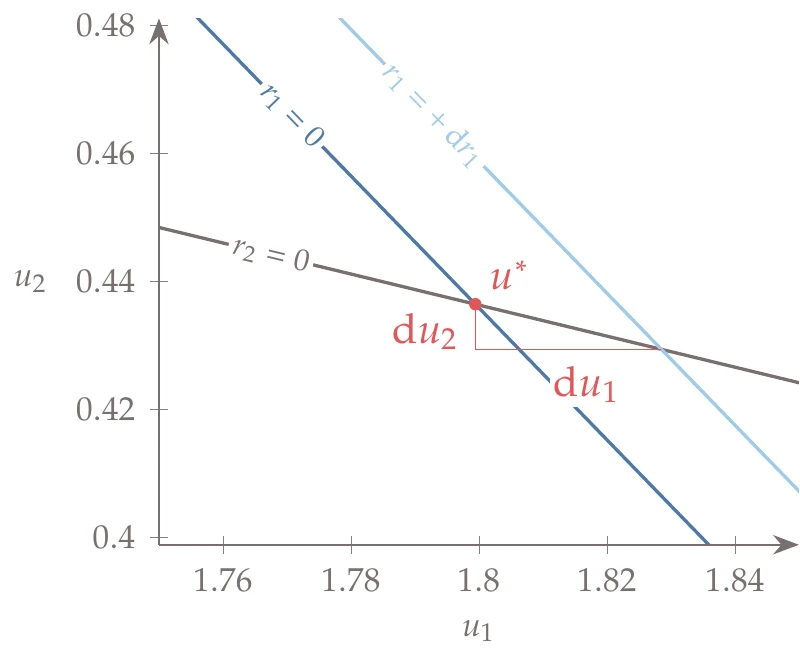

The gradient-based optimization methods introduced in Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 require the derivatives of the objective and constraints with respect to the design variables, as illustrated in Figure 6.1. Derivatives also play a central role in other numerical algorithms. For example, the Newton-based methods introduced in Section 3.8 require the derivatives of the residuals.

Figure 6.1:Efficient derivative computation is crucial for the overall efficiency of gradient-based optimization.

The accuracy and computational cost of the derivatives are critical for the success of these methods. Gradient-based methods are only efficient when the derivative computation is also efficient. The computation of derivatives can be the bottleneck in the overall optimization procedure, especially when the model solver needs to be called repeatedly. This chapter introduces the various methods for computing derivatives and discusses the relative advantages of each method.

6.1 Derivatives, Gradients, and Jacobians¶

The derivatives we focus on are first-order derivatives of one or more functions of interest () with respect to a vector of variables (). In the engineering optimization literature, the term sensitivity analysis is often used to refer to the computation of derivatives, and derivatives are sometimes referred to as sensitivity derivatives or design sensitivities. Although these terms are not incorrect, we prefer to use the more specific and concise term derivative.

For the sake of generality, we do not specify which functions we want to differentiate in this chapter (which could be an objective, constraints, residuals, or any other function). Instead, we refer to the functions being differentiated as the functions of interest and represent them as a vector-valued function, . Neither do we specify the variables with respect to which we differentiate (which could be design variables, state variables, or any other independent variable).

The derivatives of all the functions of interest with respect to all the variables form a Jacobian matrix,

which is an rectangular matrix where each row corresponds to the gradient of each function with respect to all the variables.

Row of the Jacobian is the gradient of function . Each column in the Jacobian is called the tangent with respect to a given variable . The Jacobian can be related to the operator as follows:

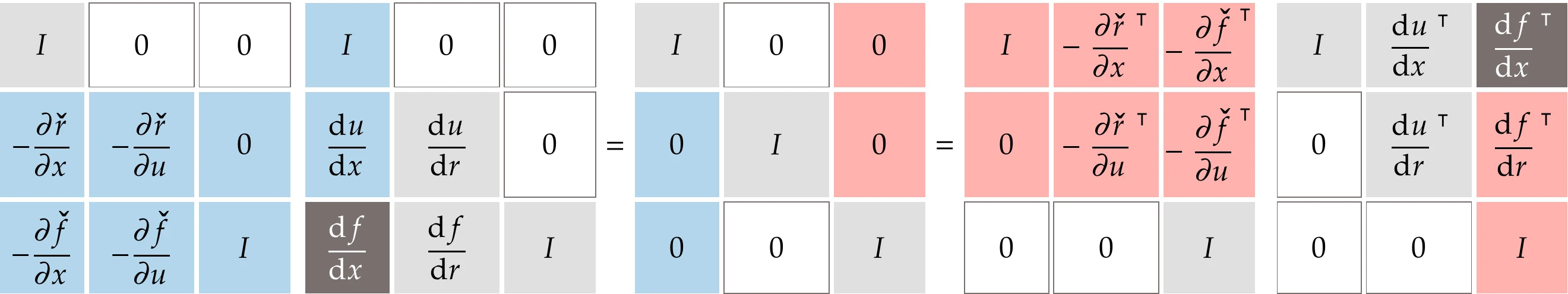

6.2 Overview of Methods for Computing Derivatives¶

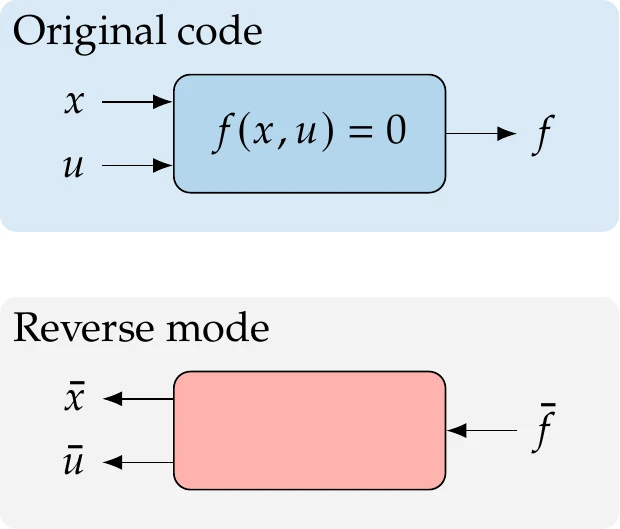

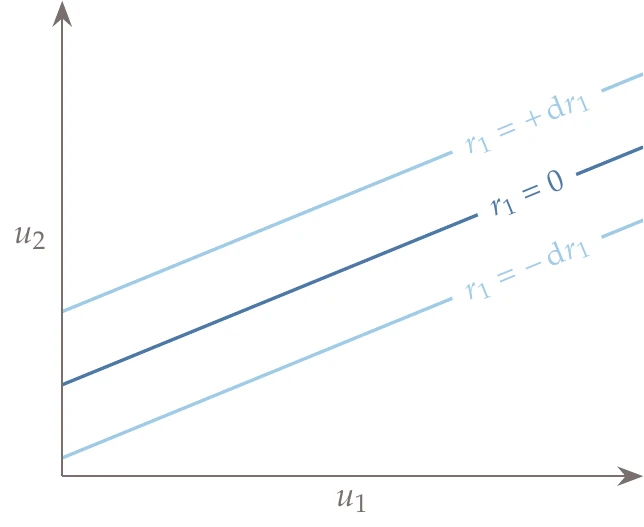

We can classify the methods for computing derivatives according to the representation used for the numerical model. There are three possible representations, as shown in Figure 6.2. In one extreme, we know nothing about the model and consider it a black box where we can only control the inputs and observe the outputs (Figure 6.2, left). In this chapter, we often refer to as the input variables and as the output variables. When this is the case, we can only compute derivatives using finite differences (Section 6.4).

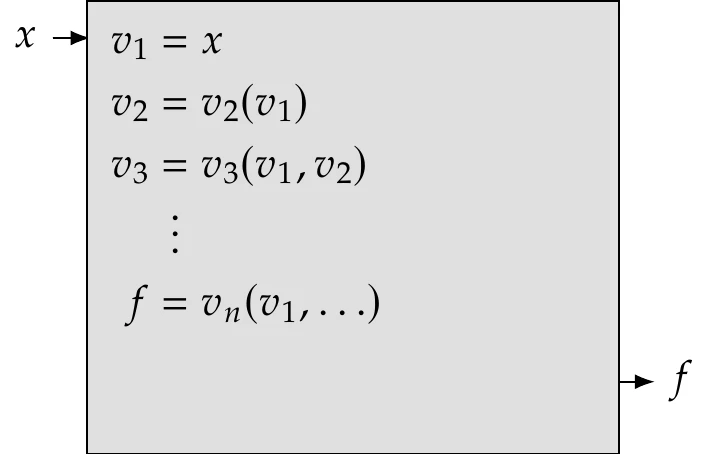

In the other extreme, we have access to the source code used to compute the functions of interest and perform the differentiation line by line (Figure 6.2, right). This is the essence of the algorithmic differentiation approach (Section 6.6). The complex-step method (Section 6.5) is related to algorithmic differentiation, as explained in Section 6.6.5.

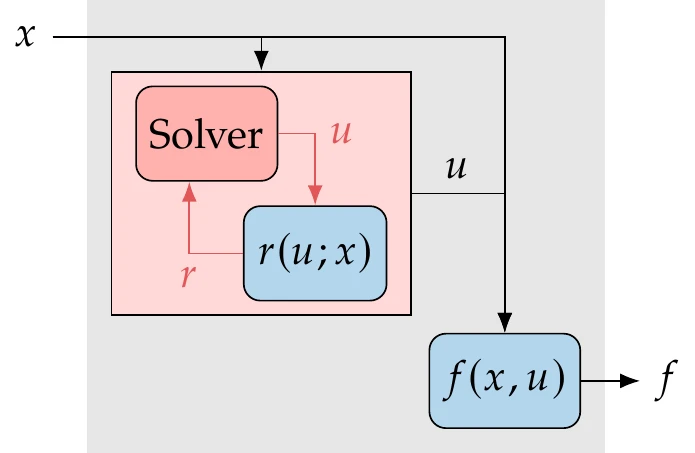

In the intermediate case, we consider the model residuals and states (Figure 6.2, middle), which are the quantities required to derive and implement implicit analytic methods (Section 6.7). When the model can be represented with multiple components, we can use a coupled derivative approach (Section 13.3) where any of these derivative computation methods can be used for each component.

Figure 6.2:Derivative computation methods can consider three different levels of information: function values (a), model states (b), and lines of code (c).

6.3 Symbolic Differentiation¶

Symbolic differentiation is well known and widely used in calculus, but it is of limited use in the numerical optimization of most engineering models. Except for the most straightforward cases (e.g., Example 6.1), many engineering models involve a large number of operations, utilize loops and various conditional logic, are implicitly defined, or involve iterative solvers (see Chapter 3). Although the mathematical expressions within these iterative procedures is explicit, it is challenging, or even impossible, to use symbolic differentiation to obtain closed-form mathematical expressions for the derivatives of the procedure. Even when it is possible, these expressions are almost always computationally inefficient.

Symbolic differentiation is still valuable for obtaining derivatives of simple explicit components within a larger model. Furthermore, algorithm differentiation (discussed in a later section) relies on symbolic differentiation to differentiate each line of code in the model.

6.4 Finite Differences¶

Because of their simplicity, finite-difference methods are a popular approach to computing derivatives. They are versatile, requiring nothing more than function values. Finite differences are the only viable option when we are dealing with black-box functions because they do not require any knowledge about how the function is evaluated. Most gradient-based optimization algorithms perform finite differences by default when the user does not provide the required gradients. However, finite differences are neither accurate nor efficient.

6.4.1 Finite-Difference Formulas¶

Finite-difference approximations are derived by combining Taylor series expansions. It is possible to obtain finite-difference formulas that estimate an arbitrary order derivative with any order of truncation error by using the right combinations of these expansions. The simplest finite-difference formula can be derived directly from a Taylor series expansion in the direction,

where is the unit vector in the direction. Solving this for the first derivative, we obtain the finite-difference formula,

where is a small scalar called the finite-difference step size.

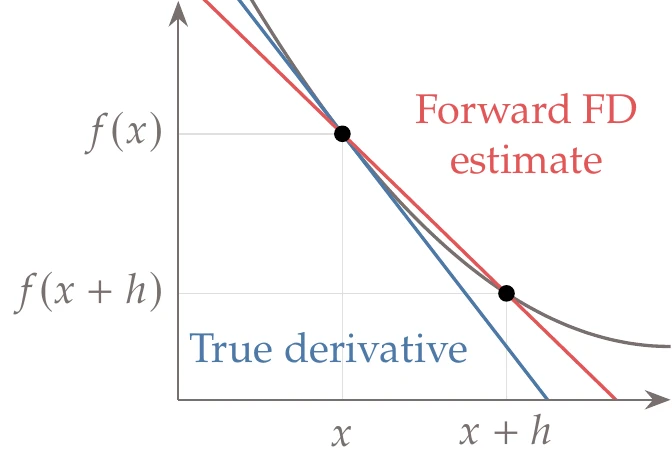

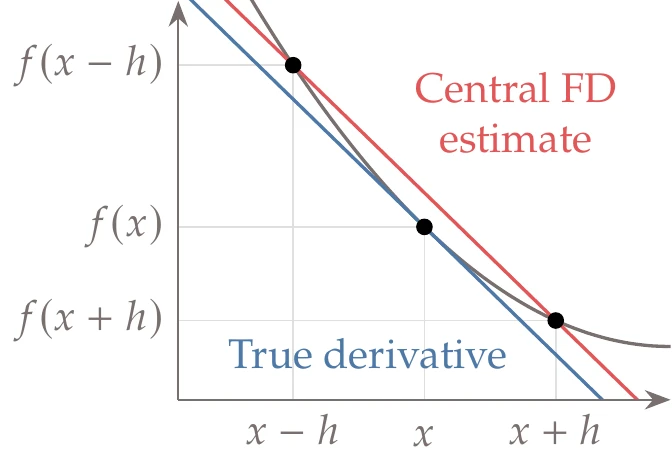

Figure 6.3:Exact derivative compared with a forward finite-difference approximation (Equation 6.4).

This approximation is called the forward difference and is directly related to the definition of a derivative because

The truncation error is , and therefore this is a first-order approximation. The difference between this approximation and the exact derivative is illustrated in Figure 6.3.

The backward-difference approximation can be obtained by replacing with to yield

which is also a first-order approximation.

Assuming each function evaluation yields the full vector , the previous formulas compute the column of the Jacobian in Equation 6.1. To compute the full Jacobian, we need to loop through each direction , add a step, recompute , and compute a finite difference. Hence, the cost of computing the complete Jacobian is proportional to the number of input variables of interest, .

For a second-order estimate of the first derivative, we can use the expansion of to obtain

Figure 6.4:Exact derivative compared with a central finite-difference approximation (Equation 6.8).

Then, if we subtract this from the expansion in Equation 6.3 and solve the resulting equation for the derivative of , we get the central-difference formula,

The stencil of points for this formula is shown in Figure 6.4, where we can see that this estimate is closer to the actual derivative than the forward difference.

Even more accurate estimates can be derived by combining different Taylor series expansions to obtain higher-order truncation error terms. This technique is widely used in finite-difference methods for solving differential equations, where higher-order estimates are desirable.

However, finite-precision arithmetic eventually limits the achievable accuracy for our purposes (as discussed in the next section). With double-precision arithmetic, there are not enough significant digits to realize a significant advantage beyond central difference.

We can also estimate second derivatives (or higher) by combining Taylor series expansions. For example, adding the expansions for and cancels out the first derivative and third derivative terms, yielding the second-order approximation to the second-order derivative,

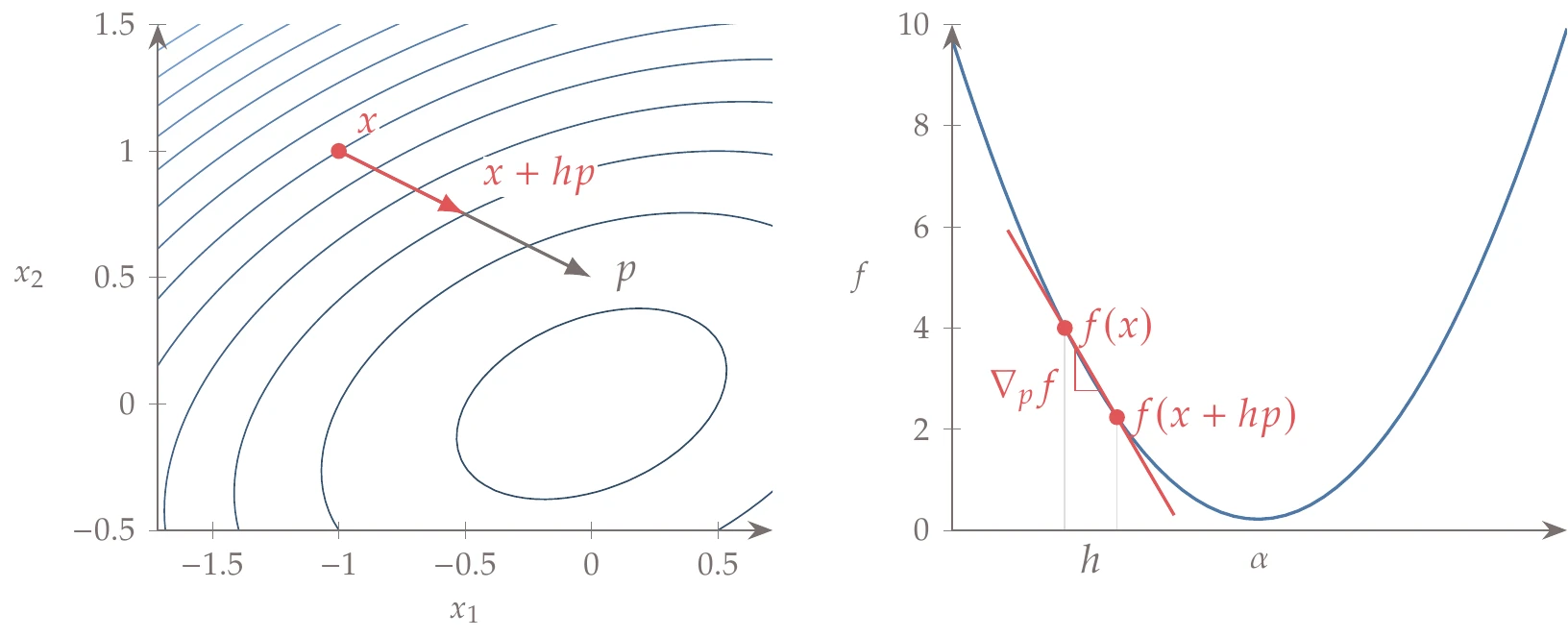

The finite-difference method can also be used to compute directional derivatives, which are the scalar projection of the gradient into a given direction. To do this, instead of stepping in orthogonal directions to get the gradient, we need to step in the direction of interest, , as shown in Figure 6.5. Using the forward difference, for example,

One application of directional derivatives is to compute the slope in line searches (Section 4.3).

Figure 6.5:Computing a directional derivative using a forward finite difference.

6.4.2 The Step-Size Dilemma¶

When estimating derivatives using finite-difference formulas, we are faced with the step-size dilemma. Because each estimate has a truncation error of (or when second order), we would like to choose as small of a step size as possible to reduce this error. However, as the step size reduces, subtractive cancellation (a roundoff error introduced in Section 3.5.1) becomes dominant. Given the opposing trends of these errors, there is an optimal step size for which the sum of the two errors is at a minimum.

Theoretically, the optimal step size for the forward finite difference is approximately , where is the precision of . The error bound is also about . For the central difference, the optimal step size scales approximately with , with an error bound of . These step and error bound estimates are just approximate and assume well-scaled problems.

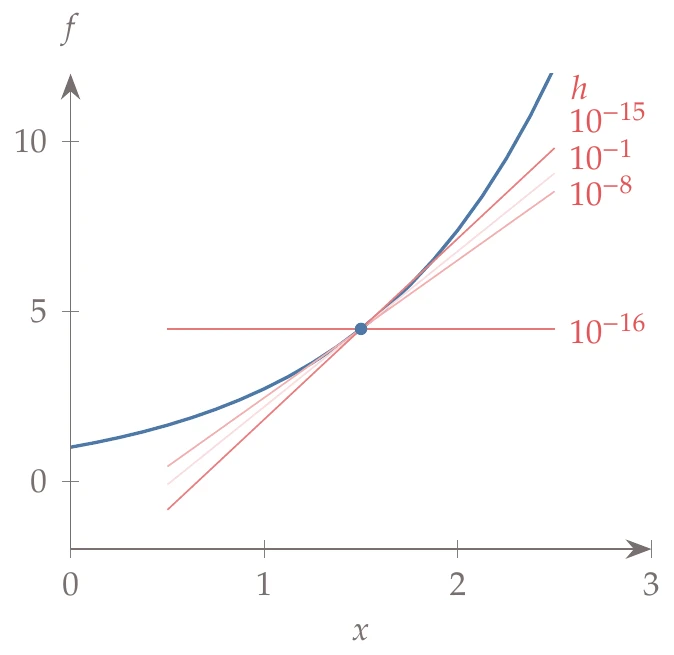

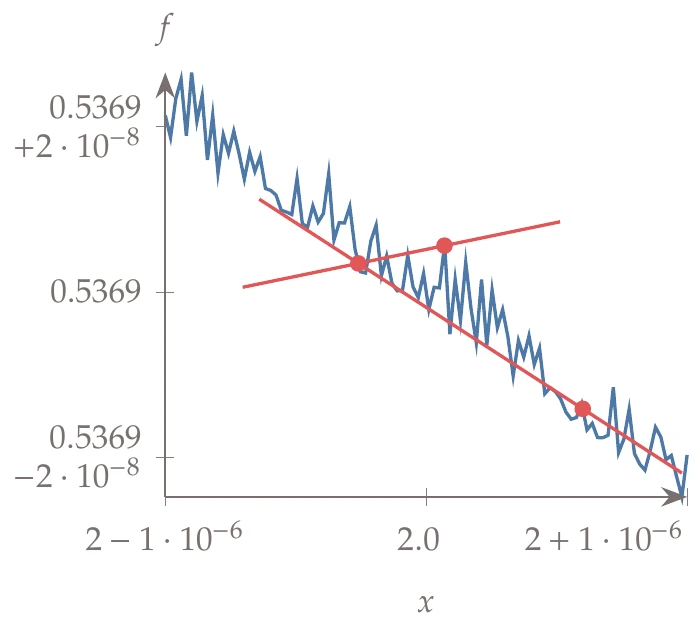

Figure 6.6:The forward-difference derivative initially improves as the step decreases but eventually gives a zero derivative for a small enough step size.

To demonstrate the step-size dilemma, consider the following function:

The exact derivative at is computed to 16 digits based on symbolic differentiation as a reference value.

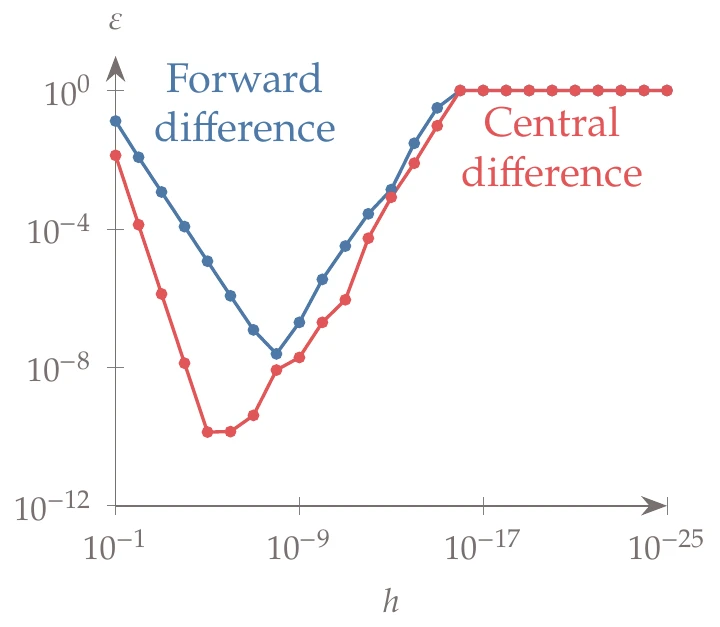

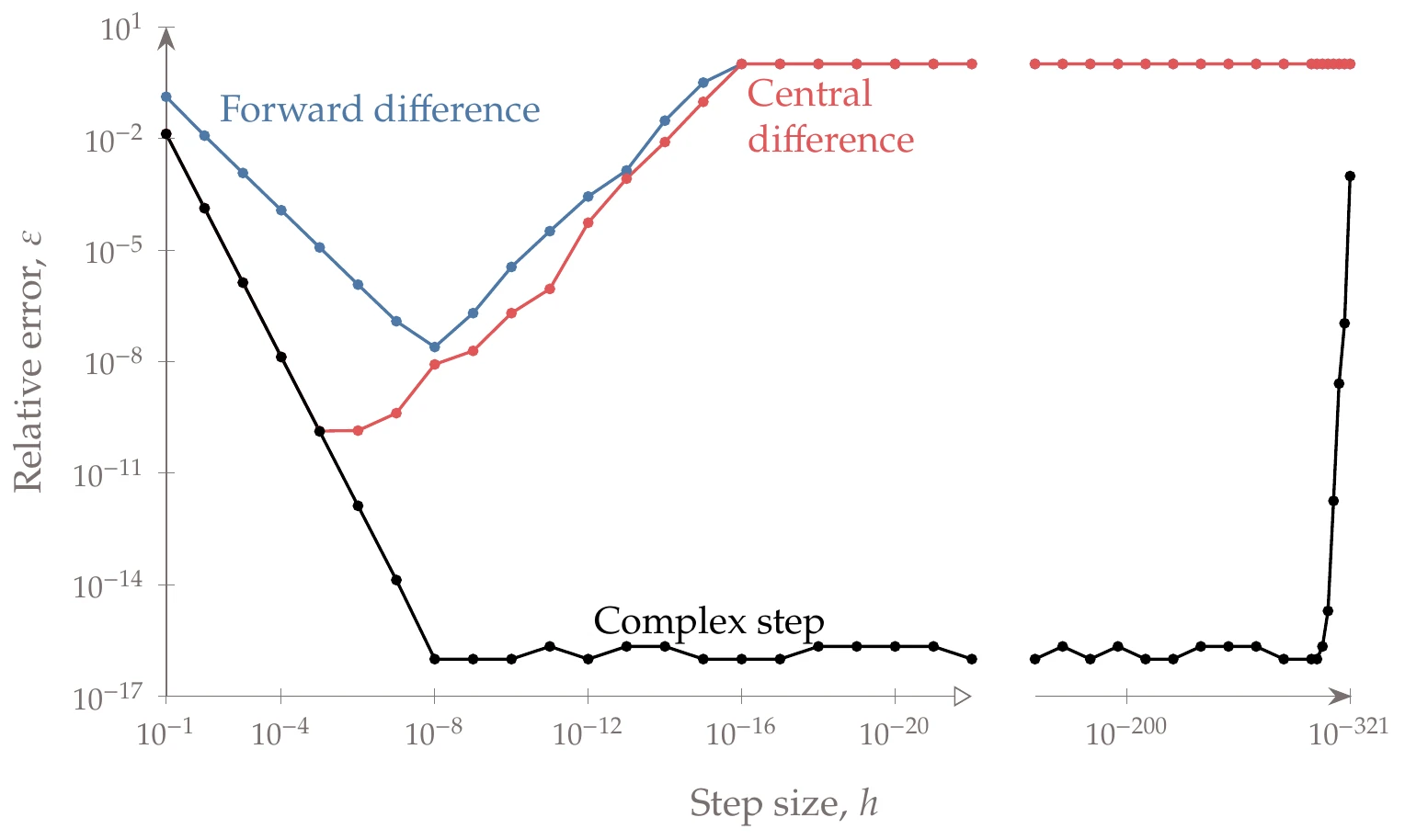

Figure 6.7:As the step size decreases, the total error in the finite-difference estimates initially decreases because of a reduced truncation error. However, subtractive cancellation takes over when the step is small enough and eventually yields an entirely wrong derivative.

In Figure 6.6, we show the derivatives given by the forward difference, where we can see that as we decrease the step size, the derivative approaches the exact value, but then it worsens and becomes zero for a small enough step size.

We plot the relative error of the forward- and central-difference formulas for a decreasing step size in Figure 6.7. As the step decreases, the forward-difference estimate initially converges at a linear rate because its truncation error is , whereas the central difference converges quadratically. However, as the step reduces below a particular value (about 10-8 for the forward difference and 10-5 for the central difference), subtractive cancellation errors become increasingly significant. These values match the theoretical predictions for the optimal step and error bounds when we set . When is so small that no difference exists in the output (for steps smaller than 10-16), the finite-difference estimates yield zero (and ), which corresponds to 100 percent error.

Table 1 lists the data for the forward difference, where we can see the number of digits in the difference decreasing with decreasing step size until the difference is zero (for ).

Table 1:Subtractive cancellation leads to a loss of precision and, ultimately, inaccurate finite-difference estimates.

| 4.9562638252880662 | 0.4584837713419043 | 4.58483771 | |

| 4.5387928890592475 | 0.0410128351130856 | 4.10128351 | |

| 4.4981854440562818 | 0.0004053901101200 | 4.05390110 | |

| 4.4977841073787870 | 0.0000040534326251 | 4.05343263 | |

| 4.4977800944804409 | 0.0000000405342790 | 4.05342799 | |

| 10-10 | 4.4977800543515052 | 0.0000000004053433 | 4.05344203 |

| 10-12 | 4.4977800539502155 | 0.0000000000040536 | 4.05453449 |

| 10-14 | 4.4977800539462027 | 0.0000000000000409 | 4.17443857 |

| 10-16 | 4.4977800539461619 | 0.0000000000000000 | 0.00000000 |

| 10-18 | 4.4977800539461619 | 0.0000000000000000 | 0.00000000 |

| Exact | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.05342789 |

In practice, most gradient-based optimizers use finite differences by default to compute the gradients. Given the potential for inaccuracies, finite differences are often the culprit in cases where gradient-based optimizers fail to converge. Although some of these optimizers try to estimate a good step size, there is no substitute for a step-size study by the user. The step-size study must be performed for all variables and does not necessarily apply to the whole design space. Therefore, repeating this study for other values of might be required.

Because we do not usually know the exact derivative, we cannot plot the error as we did in Figure 6.7. However, we can always tabulate the derivative estimates as we did in Table 1. In the last column, we can see from the pattern of digits that match the previous step size that is the best step size in this case.

Figure 6.8:Finite-differencing noisy functions can either smooth the derivative estimates or result in estimates with the wrong trends.

Finite-difference approximations are sometimes used with larger steps than would be desirable from an accuracy standpoint to help smooth out numerical noise or discontinuities in the model. This approach sometimes works, but it is better to address these problems within the model whenever possible. Figure 6.8 shows an example of this effect. For this noisy function, the larger step ignores the noise and gives the correct trend, whereas the smaller step results in an estimate with the wrong sign.

6.4.3 Practical Implementation¶

Algorithm 6.1 details a procedure for computing a Jacobian using forward finite differences. It is usually helpful to scale the step size based on the value of , unless is too small. Therefore, we combine the relative and absolute quantities to obtain the following step size:

This is similar to the expression for the convergence criterion in Equation 4.24. Although the absolute step size usually differs for each , the relative step size is often the same and is user-specified.

Inputs:

: Point about which to compute the gradient

: Vector of functions of interest

Outputs:

: Jacobian of with respect to

Evaluate reference values

Relative step size (value should be tuned)

for to do

Step size should be scaled but not smaller than

Modify in place for efficiency, but copying vector is also an option

Evaluate function at perturbed point

Finite difference yields one column of Jacobian at a time

Do not forget to reset!

end for

6.5 Complex Step¶

The complex-step derivative approximation, strangely enough, computes derivatives of real functions using complex variables. Unlike finite differences, the complex-step method requires access to the source code and cannot be applied to black-box components. The complex-step method is accurate but no more efficient than finite differences because the computational cost still scales linearly with the number of variables.

6.5.1 Theory¶

The complex-step method can also be derived using a Taylor series expansion. Rather than using a real step , as we did to derive the finite-difference formulas, we use a pure imaginary step, .[2] If is a real function in real variables and is also analytic (differentiable in the complex domain), we can expand it in a Taylor series about a real point as follows:

Taking the imaginary parts of both sides of this equation, we have

Dividing this by and solving for yields the complex-step derivative approximation,[3]

which is a second-order approximation. To use this approximation, we must provide a complex number with a perturbation in the imaginary part, compute the original function using complex arithmetic, and take the imaginary part of the output to obtain the derivative.

In practical terms, this means that we must convert the function evaluation to take complex numbers as inputs and compute complex outputs. Because we have assumed that is a real function of a real variable in the derivation of Equation 6.14, the procedure described here does not work for models that already involve complex arithmetic.

In Section 6.5.2, we explain how to convert programs to handle the required complex arithmetic for the complex-step method to work in general. The complex-step method has been extended to compute exact second derivatives as well.45

Unlike finite differences, this formula has no subtraction operation and thus no subtractive cancellation error. The only source of numerical error is the truncation error. However, the truncation error can be eliminated if is decreased to a small enough value (say, 10-200). Then, the precision of the complex-step derivative approximation (Equation 6.14) matches the precision of . This is a tremendous advantage over the finite-difference approximations (Equation 6.4 and Equation 6.8).

Like the finite-difference approach, each evaluation yields a column of the Jacobian (), and the cost of computing all the derivatives is proportional to the number of design variables. The cost of the complex-step method is comparable to that of a central difference because we compute a real and an imaginary part for every number in our code.

If we take the real part of the Taylor series expansion (Equation 6.12), we obtain the value of the function on the real axis,

Similar to the derivative approximation, we can make the truncation error disappear by using a small enough . This means that no separate evaluation of is required to get the original real value of the function; we can simply take the real part of the complex evaluation.

What is a “small enough ”? When working with finite-precision arithmetic, the error can be eliminated entirely by choosing an so small that all terms become zero because of underflow (i.e., is smaller than the smallest representable number, which is approximately 10-324 when using double precision; see Section 3.5.1). Eliminating these squared terms does not affect the accuracy of the derivative carried in the imaginary part because the squared terms only appear in the error terms of the complex-step approximation.

At the same time, must be large enough that the imaginary part () does not underflow.

Suppose that is the smallest representable number. Then, the two requirements result in the following bounds:

A step size of 10-200 works well for double-precision functions.

To show how the complex-step method works, consider the function in Example 6.3. In addition to the finite-difference relative errors from Figure 6.7, we plot the complex-step error in Figure 6.9.

Figure 6.9:Unlike finite differences, the complex-step method is not subject to subtractive cancellation. Therefore, the error is the same as that of the function evaluation (machine zero in this case).

The complex-step estimate converges quadratically with decreasing step size, as predicted by the truncation error term. The relative error reduces to machine precision at around and stays at that level. The error eventually increases when is so small that the imaginary parts get affected by underflow (around in this case).

The real parts and the derivatives of the complex evaluations are listed in Table 2. For a small enough step, the real part is identical to the original real function evaluation, and the complex-step method yields derivatives that match to machine precision.

Table 2:For a small enough step, the real part of the complex evaluation is identical to the real evaluation, and the derivative matches to machine precision.

| 4.4508662116993065 | 4.0003330384671729 | |

| 4.4973069409015318 | 4.0528918144659292 | |

| 4.4977800066307951 | 4.0534278402854467 | |

| 4.4977800539414297 | 4.0534278938932582 | |

| 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986201 | |

| 10-10 | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986201 |

| 10-12 | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986201 |

| 10-14 | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986210 |

| 10-16 | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986201 |

| 10-18 | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986210 |

| 10-200 | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986201 |

| Exact | 4.4977800539461619 | 4.0534278938986201 |

Comparing the best accuracy of each of these approaches, we can see that by using finite differences, we only achieve a fraction of the accuracy that is obtained by using the complex-step approximation.

6.5.2 Complex-Step Implementation¶

We can use the complex-step method even when the evaluation of involves the solution of numerical models through computer programs.3 The outer loop for computing the derivatives of multiple functions with respect to all variables (Algorithm 6.2) is similar to the one for finite differences. A reference function evaluation is not required, but now the function must handle complex numbers correctly.

Inputs:

: Point about which to compute the gradient

: Function of interest

Outputs:

: Jacobian of about point

Typical “small enough” step size

for to do

Add complex step to variable

Evaluate function with complex perturbation

Extract derivatives from imaginary part

Reset perturbed variable

end for

The complex-step method can be applied to any model, but modifications might be required. We need the source code for the model to make sure that the program can handle complex numbers and the associated arithmetic, that it handles logical operators consistently, and that certain functions yield the correct derivatives.

First, the program may need to be modified to use complex numbers. In programming languages like Fortran or C, this involves changing real-valued type declarations (e.g., double) to complex type declarations (e.g., double complex). In some languages, such as MATLAB, Python, and Julia, this is unnecessary because functions are overloaded to automatically accept either type.

Second, some changes may be required to preserve the correct logical flow through the program. Relational logic operators (e.g., “greater than”, “less than”, “if”, and “else”) are usually not defined for complex numbers. These operators are often used in programs, together with conditional statements, to redirect the execution thread. The original algorithm and its “complexified” version should follow the same execution thread. Therefore, defining these operators to compare only the real parts of the arguments is the correct approach. Functions that choose one argument, such as the maximum or the minimum values, are based on relational operators. Following the previous argument, we should determine the maximum and minimum values based on the real parts alone.

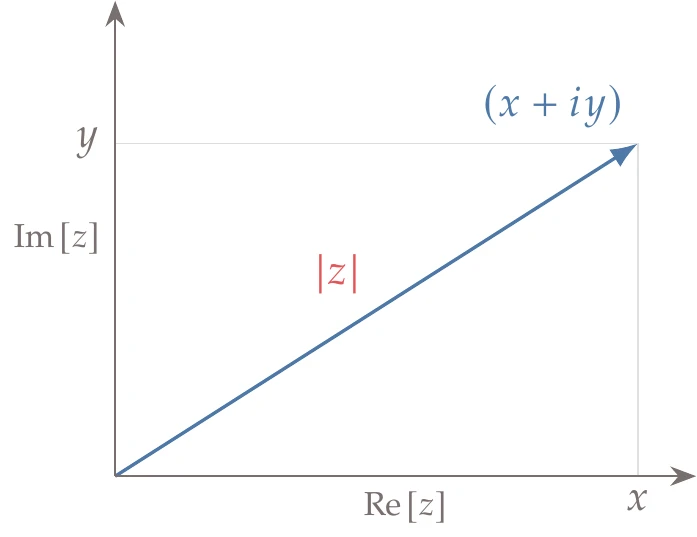

Figure 6.10:The usual definition of a complex absolute value returns a real number (the length of the vector), which is not compatible with the complex-step method.

Third, some functions need to be redefined for complex arguments. The most common function that needs to be redefined is the absolute value function. For a complex number, , the absolute value is defined as

as shown in Figure 6.10. This definition is not complex analytic, which is required in the derivation of the complex-step derivative approximation.

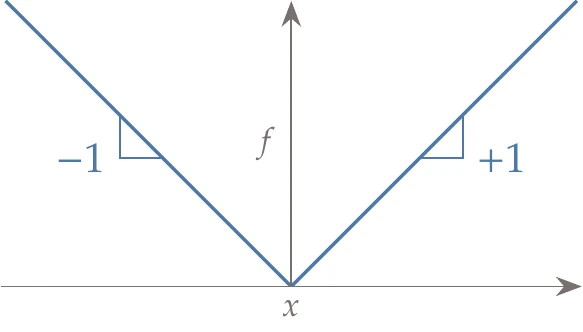

Figure 6.11:The absolute value function needs to be redefined such that the imaginary part yields the correct derivatives.

As shown in Figure 6.11, the correct derivatives for the real absolute value function are +1 and -1, depending on whether is greater than or less than zero. The following complex definition of the absolute value yields the correct derivatives:

Setting the imaginary part to and dividing by corresponds to the slope of the absolute value function. There is an exception at , where the function is not analytic, but a derivative does not exist in any case. We use the “greater or equal” in the logic so that the approximation yields the correct right-sided derivative at that point.

Once you have made your code complex, the first test you should perform is to run your code with no imaginary perturbation and verify that no variable ends up with a nonzero imaginary part. If any number in the code acquires a nonzero imaginary part, something is wrong, and you must trace the source of the error. This is a necessary but not sufficient test.

Depending on the programming language, we may need to redefine some trigonometric functions. This is because some default implementations, although correct, do not maintain accurate derivatives for small complex-step sizes.

We must replace these with mathematically equivalent implementations that avoid numerical issues.

Fortunately, we can automate most of these changes by using scripts to process the codes, and in most programming languages, we can easily redefine functions using operator overloading.[4]

When the solver that computes is iterative, it might be necessary to change the convergence criterion so that it checks for the convergence of the imaginary part, in addition to the existing check on the real part.

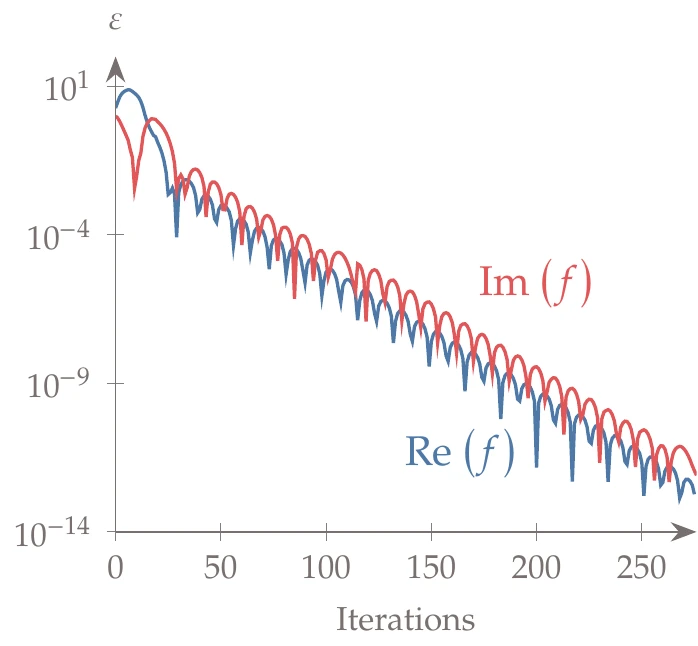

Figure 6.12:The imaginary parts of the variables often lag relative to the real parts in iterative solvers.

The imaginary part, which contains the derivative information, often lags relative to the real part in terms of convergence, as shown in Figure 6.12. Therefore, if the solver only checks for the real part, it might yield a derivative with a precision lower than the function value. In this example, is the drag coefficient given by a computational fluid dynamics solver and is the relative error for each part.

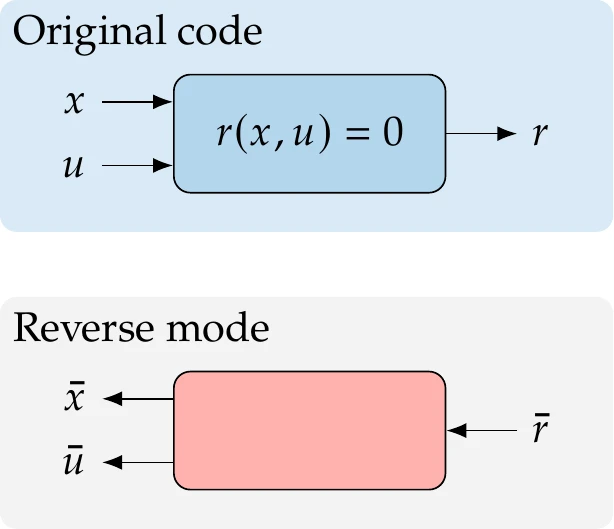

6.6 Algorithmic Differentiation¶

Algorithmic differentiation (AD)—also known as computational differentiation or automatic differentiation—is a well-known approach based on the systematic application of the chain rule to computer programs.67 The derivatives computed with AD can match the precision of the function evaluation.

The cost of computing derivatives with AD can be proportional to either the number of variables or the number of functions, depending on the type of AD, making it flexible.

Another attractive feature of AD is that its implementation is largely automatic, thanks to various AD tools. To explain AD, we start by outlining the basic theory with simple examples. Then we explore how the method is implemented in practice with further examples.

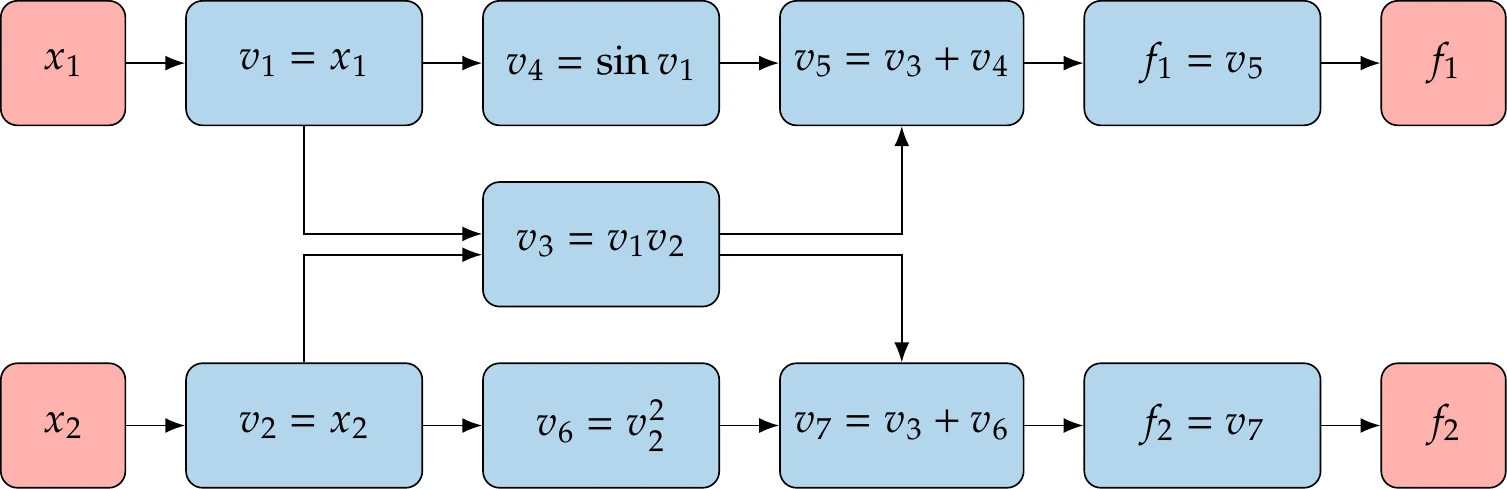

6.6.1 Variables and Functions as Lines of Code¶

The basic concept of AD is as follows. Even long, complicated codes consist of a sequence of basic operations (e.g., addition, multiplication, cosine, exponentiation). Each operation can be differentiated symbolically with respect to the variables in the expression.

AD performs this symbolic differentiation and adds the code that computes the derivatives for each variable in the code. The derivatives of each variable accumulate in what amounts to a numerical version of the chain rule.

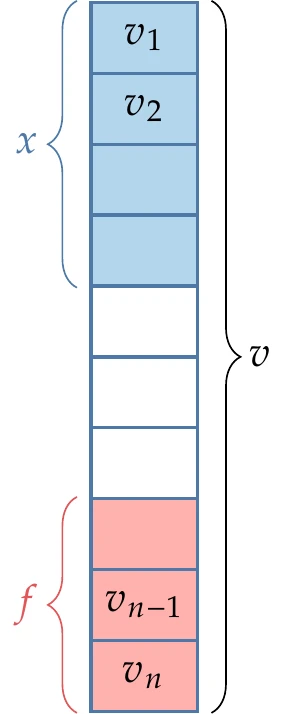

Figure 6.13:AD considers all the variables in the code, where the inputs are among the first variables, and the outputs are among the last.

The fundamental building blocks of a code are unary and binary operations. These operations can be combined to obtain more elaborate explicit functions, which are typically expressed in one line of computer code. We represent the variables in the computer code as the sequence , where is the total number of variables assigned in the code. One or more of these variables at the start of this sequence are given and correspond to , and one or more of the variables toward the end of the sequence are the outputs of interest, , as illustrated in Figure 6.13.

In general, a variable assignment corresponding to a line of code can involve any other variable, including itself, through an explicit function,

Except for the most straightforward codes, many of the variables in the code are overwritten as a result of iterative loops.

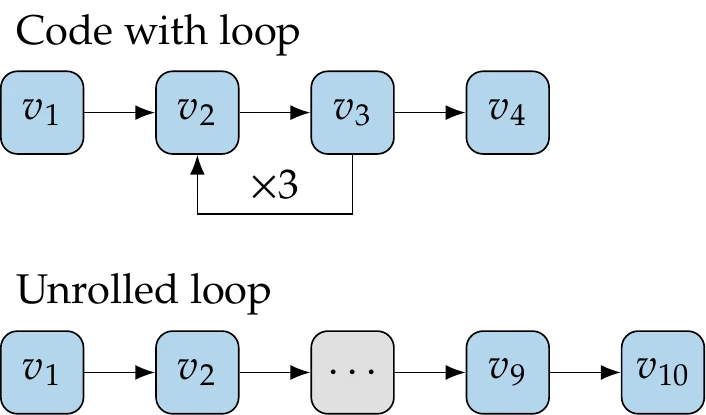

Figure 6.14:Unrolling of loops is a useful mental model to understand the derivative propagation in the AD of general code.

To understand AD, it is helpful to imagine a version of the code where all the loops are unrolled. Instead of overwriting variables, we create new versions of those variables, as illustrated in Figure 6.14. Then, we can represent the computations in the code in a sequence with no loops such that each variable in this larger set only depends on previous variables, and then

Given such a sequence of operations and the derivatives for each operation, we can apply the chain rule to obtain the derivatives for the entire sequence. Unrolling the loops is just a mental model for understanding how the chain rule operates, and it is not explicitly done in practice.

The chain rule can be applied in two ways. In the forward mode, we choose one input variable and work forward toward the outputs until we get the desired total derivative. In the reverse mode, we choose one output variable and work backward toward the inputs until we get the desired total derivative.

6.6.2 Forward-Mode AD¶

The chain rule for the forward mode can be written as

where each partial derivative is obtained by symbolically differentiating the explicit expression for . The total derivatives are the derivatives with respect to the chosen input , which can be computed using this chain rule.

Using the forward mode, we evaluate a sequence of these expressions by fixing in Equation 6.21 (effectively choosing one input ) and incrementing to get the derivative of each variable . We only need to sum up to because of the form of Equation 6.20, where each only depends on variables that precede it.

For a more convenient notation, we define a new variable that represents the total derivative of variable with respect to a fixed input as and rewrite the chain rule as

The chosen input corresponds to the seed, which we set to (using the definition for , we see that means setting ).

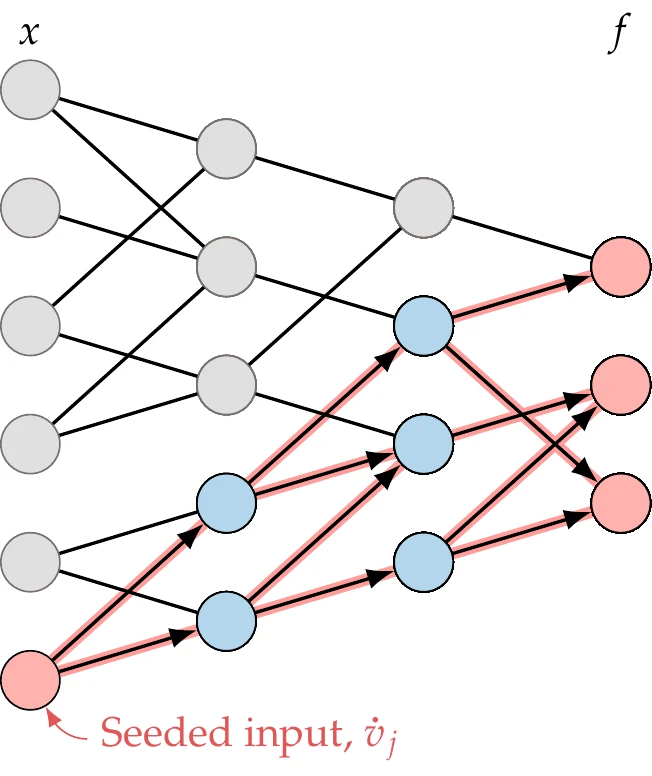

Figure 6.15:The forward mode propagates derivatives to all the variables that depend on the seeded input variable.

This chain rule then propagates the total derivatives forward, as shown in Figure 6.15, affecting all the variables that depend on the seeded variable.

Once we are done applying the chain rule (Equation 6.22) for the chosen input variable , we end up with the total derivatives for all . The sum in the chain rule (Equation 6.22) only needs to consider the nonzero partial derivative terms. If a variable does not explicitly appear in the expression for , then , and there is no need to consider the corresponding term in the sum. In practice, this means that only a small number of terms is considered for each sum.

Suppose we have four variables , and , and , , and we want . We assume that each variable depends explicitly on all the previous ones. Using the chain rule (Equation 6.22), we set (because we want the derivative with respect to ) and increment in to get the sequence of derivatives:

In each step, we just need to compute the partial derivatives of the current operation and then multiply using the total derivatives that have already been computed. We move forward by evaluating the partial derivatives of in the same sequence to evaluate the original function.

This is convenient because all of the unknowns are partial derivatives, meaning that we only need to compute derivatives based on the operation at hand (or line of code).

In this abstract example with four variables that depend on each other sequentially, the Jacobian of the variables with respect to themselves is as follows:

By setting the seed and using the forward chain rule (Equation 6.22), we have computed the first column of from top to bottom. This column corresponds to the tangent with respect to . Using forward-mode AD, obtaining derivatives for other outputs is free (e.g., in Equation 6.23).

However, if we want the derivatives with respect to additional inputs, we would need to set a different seed and evaluate an entire set of similar calculations. For example, if we wanted , we would set the seed as and evaluate the equations for and , where we would now have . This would correspond to computing the second column in (Equation 6.24).

Thus, the cost of the forward mode scales linearly with the number of inputs we are interested in and is independent of the number of outputs.

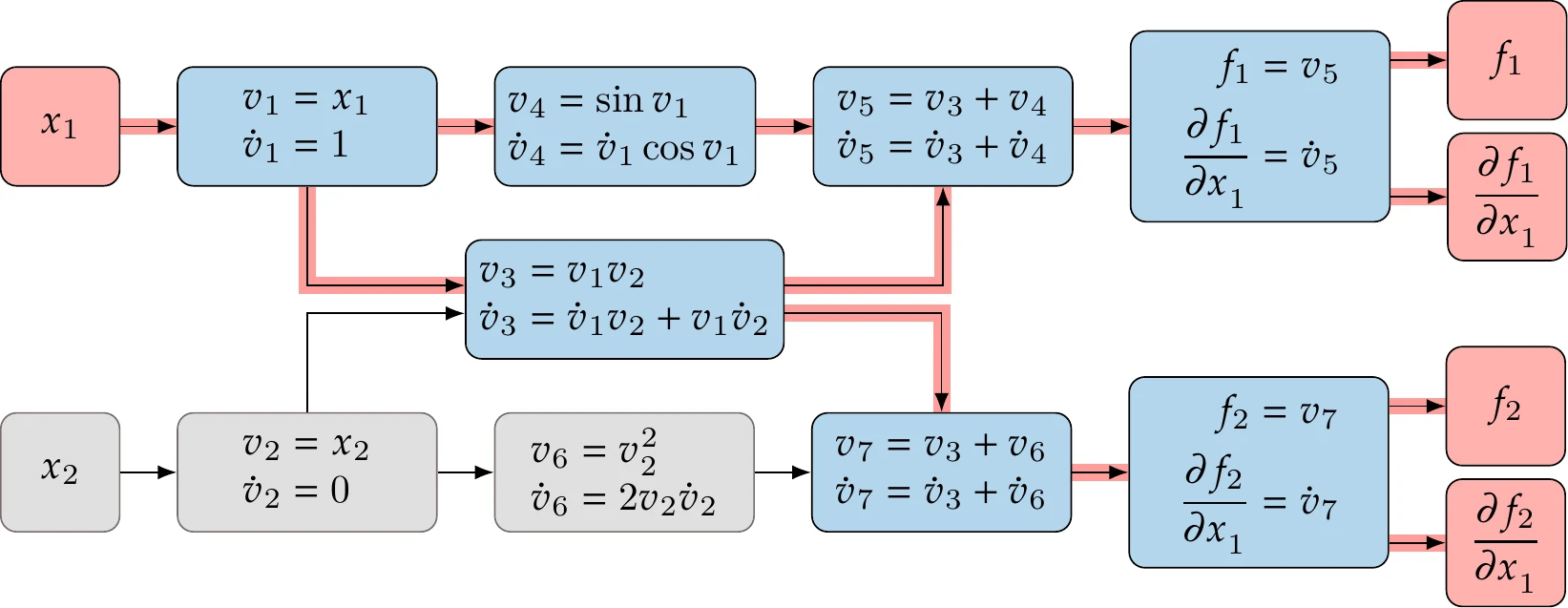

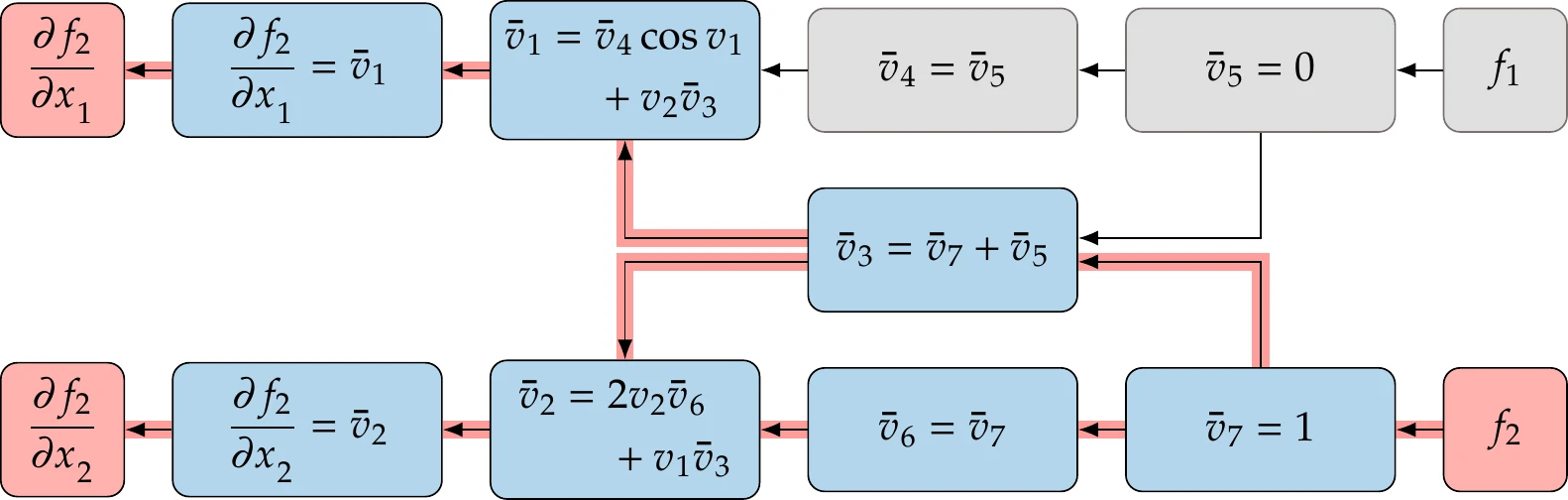

Consider the function with two inputs and two outputs from Example 6.1. We could evaluate the explicit expressions in this function using only two lines of code. However, to make the AD process more apparent, we write the code such that each line has a single unary or binary operation, which is how a computer ends up evaluating the expression:

Using the forward mode, set the seed , and to obtain the derivatives with respect to . When using the chain rule (Equation 6.22), only one or two partial derivatives are nonzero in each sum because the operations are either unary or binary in this case. For example, the addition operation that computes does not depend explicitly on , so . To further elaborate, when evaluating the operation , we do not need to know how was computed; we just need to know the value of the two numbers we are adding. Similarly, when evaluating the derivative , we do not need to know how or whether and depended on ; we just need to know how this one operation depends on . So even though symbolic derivatives are involved in individual operations, the overall process is distinct from symbolic differentiation. We do not combine all the operations and end up with a symbolic derivative. We develop a computational procedure to compute the derivative that ends up with a number for a given input—similar to the computational procedure that computes the functional outputs and does not produce a symbolic functional output.

Say we want to compute , which in our example corresponds to . The evaluation point is the same as in Example 6.1: . Using the chain rule (Equation 6.22) and considering only the nonzero partial derivative terms, we get the following sequence:

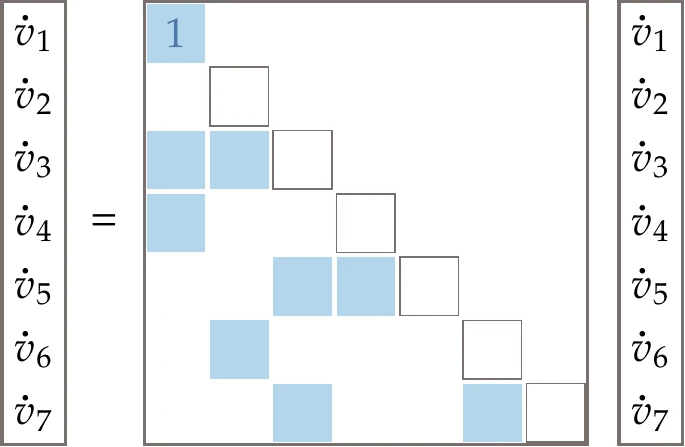

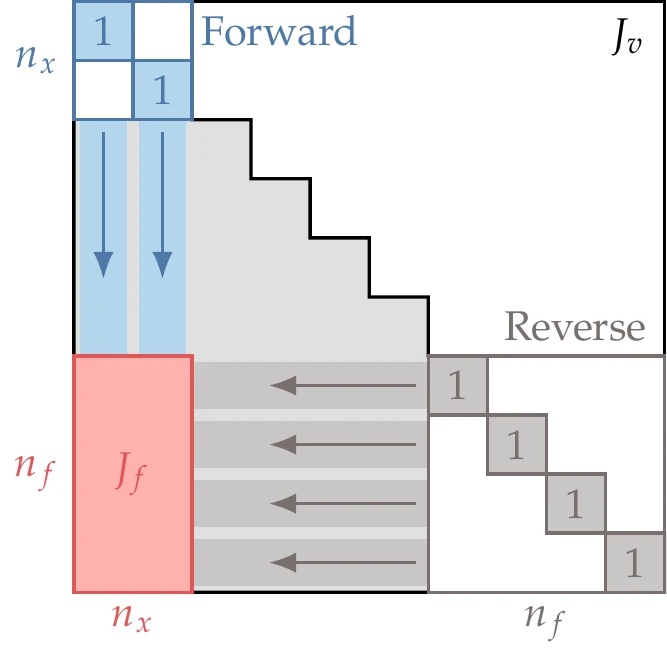

This sequence is illustrated in matrix form in Figure 6.16. The procedure is equivalent to performing forward substitution in this linear system.

Figure 6.16:Dependency used in the forward chain rule propagation in Equation 6.25. The forward mode is equivalent to solving a lower triangular system by forward substitution, where the system is sparse.

We now have a procedure (not a symbolic expression) for computing for any . The dependencies of these operations are shown in Figure 6.17 as a computational graph.

Although we set out to compute , we also obtained as a by-product. We can obtain the derivatives for all outputs with respect to one input for the same cost as computing the outputs. If we wanted the derivative with respect to the other input, , a new sequence of calculations would be necessary.

Figure 6.17:Computational graph for the numerical example evaluations, showing the forward propagation of the derivative with respect to .

So far, we have assumed that we are computing derivatives with respect to each component of . However, just like for finite differences, we can also compute directional derivatives using forward-mode AD. We do so by setting the appropriate seed in the ’s that correspond to the inputs in a vectorized manner. Suppose we have . To compute the derivative with respect to , we would set the seed as the unit vector and follow a similar process for the other elements. To compute a directional derivative in direction , we would set the seed as .

We can use a directional derivative in arbitrary directions to verify the gradient computation. The directional derivative is the scalar projection of the gradient in the chosen direction, that is, . We can use the directional derivative to verify the gradient computed by some other method, which is especially useful when the evaluation of is expensive and we have many gradient elements. We can verify a gradient by projecting it into some direction (say, ) and then comparing it to the directional derivative in that direction. If the result matches the reference, then all the gradient elements are most likely correct (it is good practice to try a couple more directions just to be sure). However, if the result does not match, this directional derivative does not reveal which gradient elements are incorrect.

6.6.3 Reverse-Mode AD¶

The reverse mode is also based on the chain rule but uses the alternative form:

where the summation happens in reverse (starts at and decrements to ). This is less intuitive than the forward chain rule, but it is equally valid. Here, we fix the index corresponding to the output of interest and decrement until we get the desired derivative.

Similar to the forward-mode total derivative notation (Equation 6.22), we define a more convenient notation for the variables that carry the total derivatives with a fixed as ,

which are sometimes called adjoint variables. Then we can rewrite the chain rule as

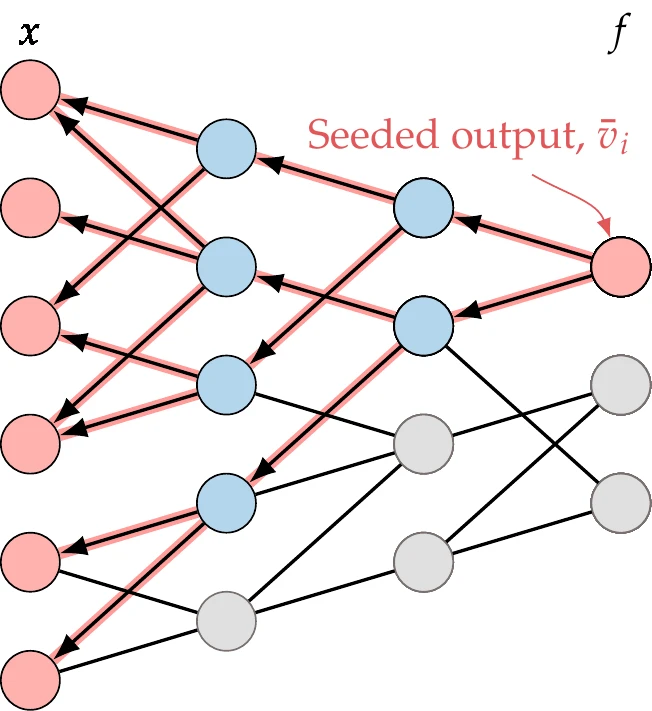

This chain rule propagates the total derivatives backward after setting the reverse seed , as shown in Figure 6.18.

Figure 6.18:The reverse mode propagates derivatives to all the variables on which the seeded output variable depends.

This affects all the variables on which the seeded variable depends.

The reverse-mode variables represent the derivatives of one output, , with respect to all the input variables (instead of the derivatives of all the outputs with respect to one input, , in the forward mode). Once we are done applying the reverse chain rule (Equation 6.27) for the chosen output variable , we end up with the total derivatives for all .

Applying the reverse mode to the same four-variable example as before, we get the following sequence of derivative computations (we set and decrement ):

The partial derivatives of must be computed for first, then , and so on. Therefore, we have to traverse the code in reverse. In practice, not every variable depends on every other variable, so a computational graph is created during code evaluation. Then, when computing the adjoint variables, we traverse the computational graph in reverse. As before, the derivatives we need to compute in each line are only partial derivatives.

Recall the Jacobian of the variables,

By setting and using the reverse chain rule (Equation 6.27), we have computed the last row of from right to left. This row corresponds to the gradient of . Using the reverse mode of AD, obtaining derivatives with respect to additional inputs is free (e.g., in Equation 6.28).

However, if we wanted the derivatives of additional outputs, we would need to evaluate a different sequence of derivatives. For example, if we wanted , we would set and evaluate the expressions for and in Equation 6.28, where . Thus, the cost of the reverse mode scales linearly with the number of outputs and is independent of the number of inputs.

One complication with the reverse mode is that the resulting sequence of derivatives requires the values of the variables, starting with the last ones and progressing in reverse. For example, the partial derivative in the second operation of Equation 6.28 might involve . Therefore, the code needs to run in a forward pass first, and all the variables must be stored for use in the reverse pass, which increases memory usage.

Suppose we want to compute for the function from Example 6.5. First, we need to run the original code (a forward pass) and store the values of all the variables because they are necessary in the reverse chain rule (Equation 6.26) to compute the numerical values of the partial derivatives. Furthermore, the reverse chain rule requires the information on all the dependencies to determine which partial derivatives are nonzero. The forward pass and dependencies are represented by the computational graph shown in Figure 6.19.

Figure 6.19:Computational graph for the function.

Using the chain rule (Equation 6.26) and setting the seed for the desired variable , we get

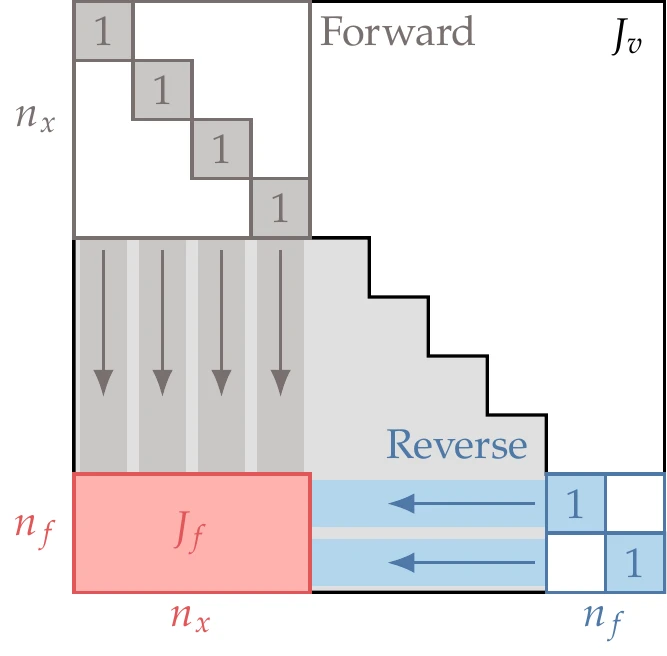

After running the forward evaluation and storing the elements of , we can run the reverse pass shown in Figure 6.20. This reverse pass is illustrated in matrix form in Figure 6.21. The procedure is equivalent to performing back substitution in this linear system.

Figure 6.20:Computational graph for the reverse mode, showing the backward propagation of the derivative of .

Although we set out to evaluate , we also computed as a by-product. For each output, the derivatives of all inputs come at the cost of evaluating only one more line of code. Conversely, if we want the derivatives of , a whole new set of computations is needed.

Figure 6.21:Dependency used in the reverse chain rule propagation in Equation 6.30. The reverse mode is equivalent to solving an upper triangular system by backward substitution, where the system is sparse.

In forward mode, the computation of a given derivative, , requires the partial derivatives of the line of code that computes with respect to its inputs.

In the reverse case, however, to compute a given derivative, , we require the partial derivatives with respect to of the functions that the current variable affects. Knowledge of the function a variable affects is not encoded in that variable computation, and that is why the computational graph is required.

Unlike with forward-mode AD and finite differences, it is impossible to compute a directional derivative by setting the appropriate seeds.

Although the seeds in the forward mode are associated with the inputs, the seeds for the reverse mode are associated with the outputs. Suppose we have multiple functions of interest, . To find the derivatives of in a vectorized operation, we would set .

A seed with multiple nonzero elements computes the derivatives of a weighted function with respect to all the variables, where the weight for each function is determined by the corresponding value.

6.6.4 Forward Mode or Reverse Mode?¶

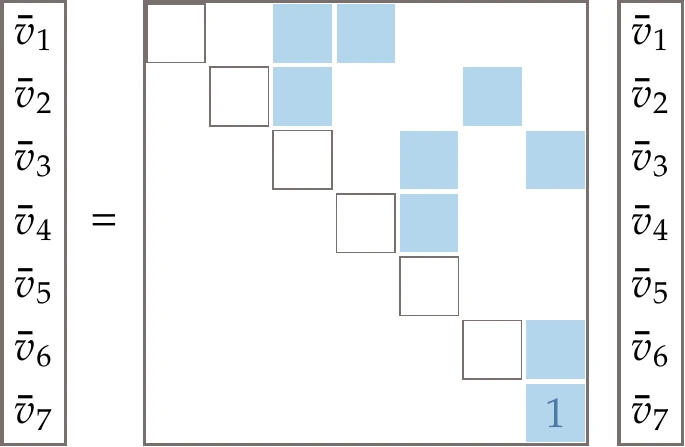

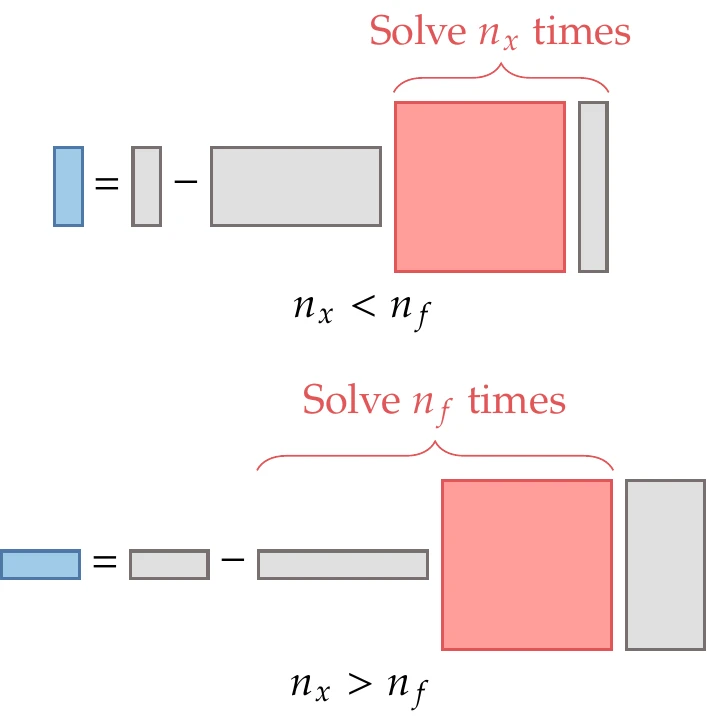

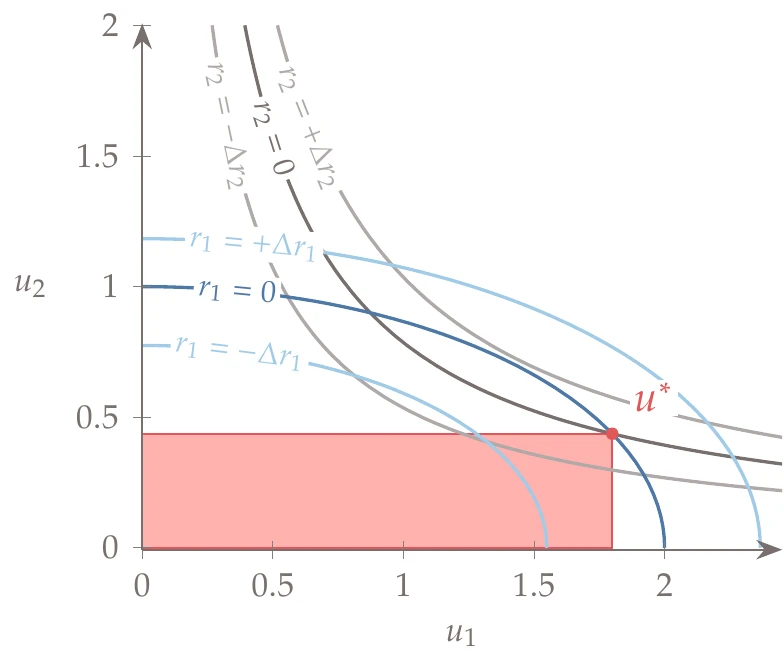

Our goal is to compute , the () matrix of derivatives of all the functions of interest with respect to all the input variables . However, AD computes many other derivatives corresponding to intermediate variables. The complete Jacobian for all the intermediate variables, , assuming that the loops have been unrolled, has the structure shown in Figure 6.22 and Figure 6.23.

The input variables are among the first entries in , whereas the functions of interest are among the last entries of .

Figure 6.22:When , the forward mode is advantageous.

For simplicity, let us assume that the entries corresponding to and are contiguous, as previously shown in Figure 6.13. Then, the derivatives we want () are a block located on the lower left in the much larger matrix (), as shown in Figure 6.22 and Figure 6.23. Although we are only interested in this block, AD requires the computation of additional intermediate derivatives.

Figure 6.23:When , the reverse mode is advantageous.

The main difference between the forward and the reverse approaches is that the forward mode computes the Jacobian column by column, whereas the reverse mode does it row by row. Thus, the cost of the forward mode is proportional to , whereas the cost of the reverse mode is proportional to . If we have more outputs (e.g., objective and constraints) than inputs (design variables), the forward mode is more efficient, as illustrated in Figure 6.22. On the other hand, if we have many more inputs than outputs, then the reverse mode is more efficient, as illustrated in Figure 6.23. If the number of inputs is similar to the number of outputs, neither mode has a significant advantage.

In both modes, each forward or reverse pass costs less than 2–3 times the cost of running the original code in practice. However, because the reverse mode requires storing a large amount of data, memory costs also need to be considered. In principle, the required memory is proportional to the number of variables, but there are techniques that can reduce the memory usage significantly.[5]

6.6.5 AD Implementation¶

There are two main ways to implement AD: by source code transformation or by operator overloading. The function we used to demonstrate the issues with symbolic differentiation (Example 6.2) can be differentiated much more easily with AD. In the examples that follow, we use this function to demonstrate how the forward and reverse mode work using both source code transformation and operator overloading.

Source Code Transformation¶

AD tools that use source code transformation process the whole source code automatically with a parser and add lines of code that compute the derivatives. The added code is highlighted in Example 6.7 and Example 6.8.

Running an AD source transformation tool on the code from Example 6.2 produces the code that follows.

Require: , Set seed to get

Automatically added by AD tool

for to 10 do

Automatically added by AD tool

end for

Ensure: , is given by

The AD tool added a new line after each variable assignment that computes the corresponding derivative. We can then set the seed, and run the code. As the loops proceed, accumulates the derivative as is successively updated.

The reverse-mode AD version of the code from Example 6.2 follows.

Require: , Set to get

for to 10 do

push() Save current value of on top of stack

end for

for to 1 doReverse loop added by AD tool = pop() Get value of from top of stack end for

Ensure: , is given by

The first loop is identical to the original code except for one line. Because the derivatives that accumulate in the reverse loop depend on the intermediate values of the variables, we need to store all the variables in the forward loop. We store and retrieve the variables using a stack, hence the call to “push”.[6]The second loop, which runs in reverse, is where the derivatives are computed. We set the reverse seed, , and then the adjoint variables accumulate the derivatives back to the start.

Operator Overloading¶

The operator overloading approach creates a new augmented data type that stores both the variable value and its derivative. Every floating-point number is replaced by a new type with two parts , commonly referred to as a dual number. All standard operations (e.g., addition, multiplication, sine) are overloaded such that they compute according to the original function value and according to the derivative of that function. For example, the multiplication operation, , would be defined for the dual-number data type as

where we compute the original function value in the first term, and the second term carries the derivative of the multiplication.

Although we wrote the two parts explicitly in Equation 6.31, the source code would only show a normal multiplication, such as . However, each of these variables would be of the new type and carry the corresponding quantities. By overloading all the required operations, the computations happen “behind the scenes”, and the source code does not have to be changed, except to declare all the variables to be of the new type and to set the seed. Example 6.9 lists the original code from Example 6.2 with notes on the actual computations that are performed as a result of overloading.

Using the derived data types and operator overloading approach in forward mode does not change the code listed in Example 6.2. The AD tool provides overloaded versions of the functions in use, which in this case are assignment, addition, and sine. These functions are overloaded as follows:

In this case, the source code is unchanged, but additional computations occur through the overloaded functions. We reproduce the code that follows with notes on the hidden operations that take place.

Require: is of a new data type with two components

through the overloading of the “” operation

for to 10 do

Code is unchanged, but overloading

computes the derivative[7]

end for

Ensure: The new data type includes , which is

We set the seed, , and for each function assignment, we add the corresponding derivative line. As the loops are repeated, accumulates the derivative as is successively updated.

The implementation of the reverse mode using operating overloading is less straightforward and is not detailed here. It requires a new data type that stores the information from the computational graph and the variable values when running the forward pass. This information can be stored using the taping technique. After the forward evaluation of using the new type, the “tape” holds the sequence of operations, which is then evaluated in reverse to propagate the reverse-mode seed.[8]

Connection of AD with the Complex-Step Method¶

The complex-step method from Section 6.5 can be interpreted as forward-mode AD using operator overloading, where the data type is the complex number , and the imaginary part carries the derivative. To see this connection more clearly, let us write the complex multiplication operation as

This equation is similar to the overloaded multiplication (Equation 6.31). The only difference is that the real part includes the term , which corresponds to the second-order error term in Equation 6.15. In this case, the complex part gives the exact derivative, but a second-order error might appear for other operations. As argued before, these errors vanish in finite-precision arithmetic if the complex step is small enough.

There are AD tools available for most programming languages, including Fortran,89 C/C++,10 Python,1112, Julia,13 and MATLAB.14 These tools have been extensively developed and provide the user with great functionality, including the calculation of higher-order derivatives, multivariable derivatives, and reverse-mode options. Although some AD tools can be applied recursively to yield higher-order derivatives, this approach is not typically efficient and is sometimes unstable.15

Source Code Transformation versus Operator Overloading¶

The source code transformation and the operator overloading approaches each have their relative advantages and disadvantages. The overloading approach is much more elegant because the original code stays practically the same and can be maintained directly. On the other hand, the source transformation approach enlarges the original code and results in less readable code, making it hard to work with. Still, it is easier to see what operations take place when debugging. Instead of maintaining source code transformed by AD, it is advisable to work with the original source and devise a workflow where the parser is rerun before compiling a new version.

One advantage of the source code transformation approach is that it tends to yield faster code and allows more straightforward compile-time optimizations. The overloading approach requires a language that supports user-defined data types and operator overloading, whereas source transformation does not. Developing a source transformation AD tool is usually more challenging than developing the overloading approach because it requires an elaborate parser that understands the source syntax.

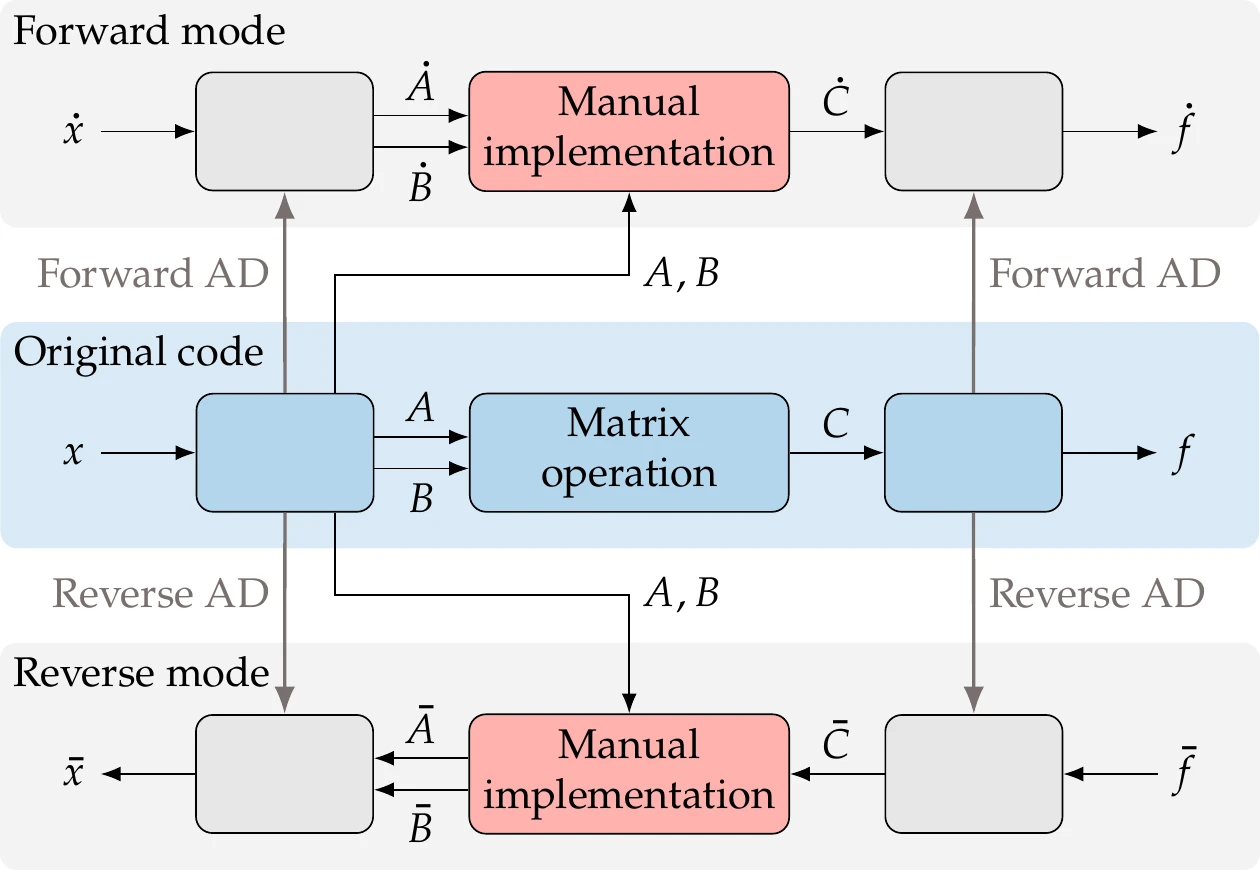

6.6.6 AD Shortcuts for Matrix Operations¶

The efficiency of AD can be dramatically increased with manually implemented shortcuts. When the code involves matrix operations, manual implementation of a higher-level differentiation of those operations is more efficient than the line-by-line AD implementation. Giles (2008) documents the forward and reverse differentiation of many matrix elementary operations.

For example, suppose that we have a matrix multiplication . Then, the forward mode yields

The idea is to use and from the AD code preceding the operation and then manually implement this formula (bypassing any AD of the code that performs that operation) to obtain , as shown in Figure 6.24. Then we can use to seed the remainder of the AD code.

The reverse mode of the multiplication yields

Similarly, we take from the reverse AD code and implement the formula manually to compute and , which we can use in the remaining AD code in the reverse procedure.

Figure 6.24:Matrix operations, including the solution of linear systems, can be differentiated manually to bypass more costly AD code.

One particularly useful (and astounding!) result is the differentiation of the matrix inverse product. If we have a linear solver such that , we can bypass the solver in the AD process by using the following results:

for the forward mode and

for the reverse mode.

In addition to deriving the formulas just shown, Giles (2008) derives formulas for the matrix derivatives of the inverse, determinant, norms, quadratic, polynomial, exponential, eigenvalues and eigenvectors, and singular value decomposition. Taking shortcuts as described here applies more broadly to any case where a part of the process can be differentiated manually to produce a more efficient derivative computation.

6.7 Implicit Analytic Methods—Direct and Adjoint¶

Direct and adjoint methods—which we refer to jointly as implicit analytic methods—linearize the model governing equations to obtain a system of linear equations whose solution yields the desired derivatives. Like the complex-step method and AD, implicit analytic methods compute derivatives with a precision matching that of the function evaluation.

The direct method is analogous to forward-mode AD, whereas the adjoint method is analogous to reverse-mode AD.

Analytic methods can be thought of as lying in between the finite-difference method and AD in terms of the number of variables involved. With finite differences, we only need to be aware of inputs and outputs, whereas AD involves every single variable assignment in the code. Analytic methods work at the model level and thus require knowledge of the governing equations and the corresponding state variables.

There are two main approaches to deriving implicit analytic methods: continuous and discrete. The continuous approach linearizes the original continuous governing equations, such as a partial differential equation (PDE), and then discretizes this linearization. The discrete approach linearizes the governing equations only after they have been discretized as a set of residual equations, .

Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages. The discrete approach is preferred and is easier to generalize, so we explain this approach exclusively. One of the primary reasons the discrete approach is preferred is that the resulting derivatives are consistent with the function values because they use the same discretization. The continuous approach is only consistent in the limit of a fine discretization. The resulting inconsistencies can mislead the optimization.[9]

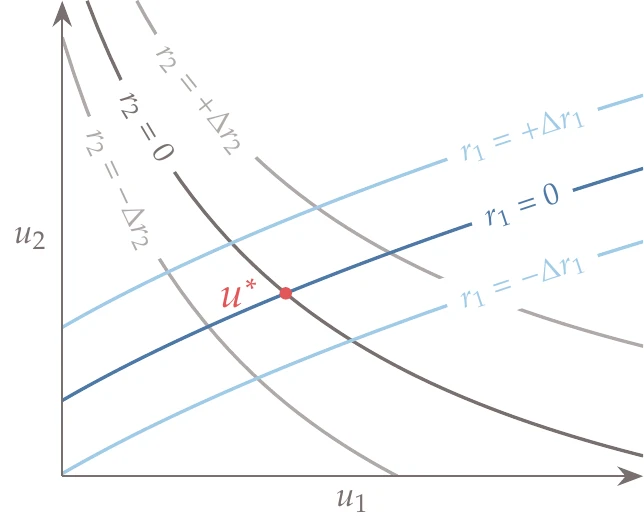

6.7.1 Residuals and Functions¶

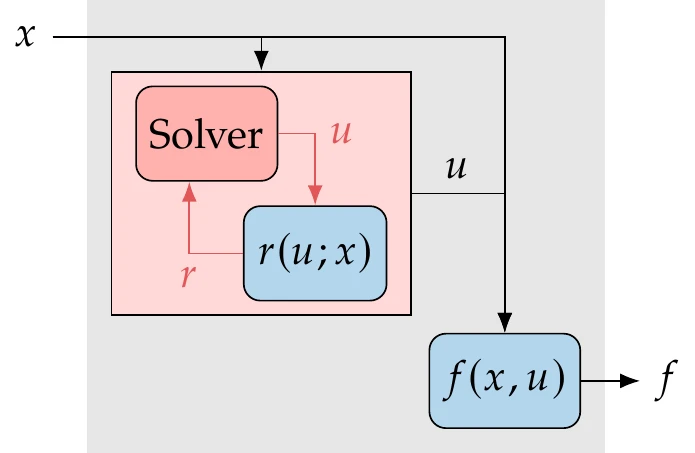

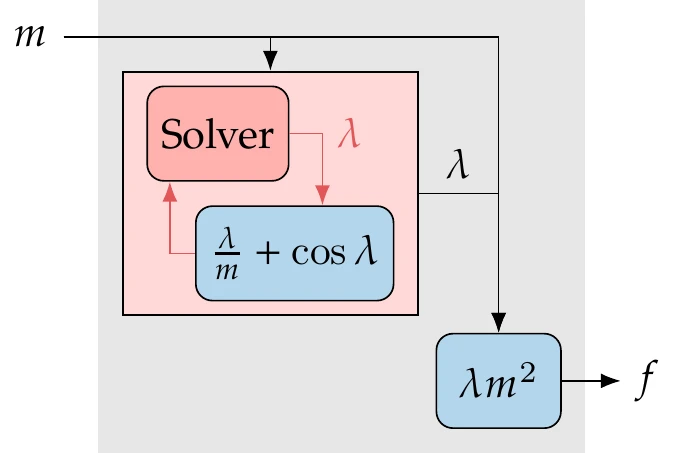

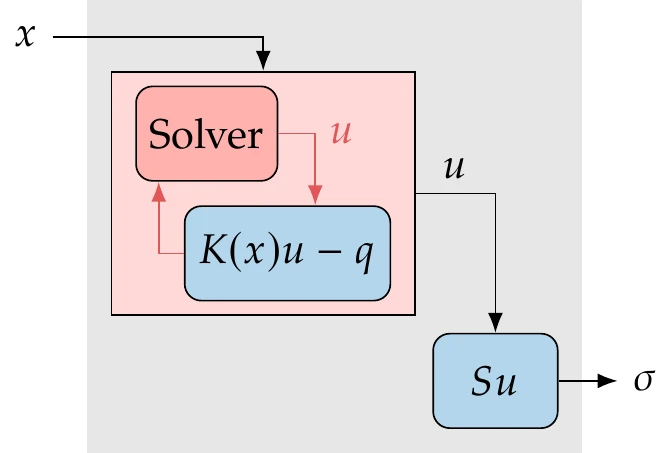

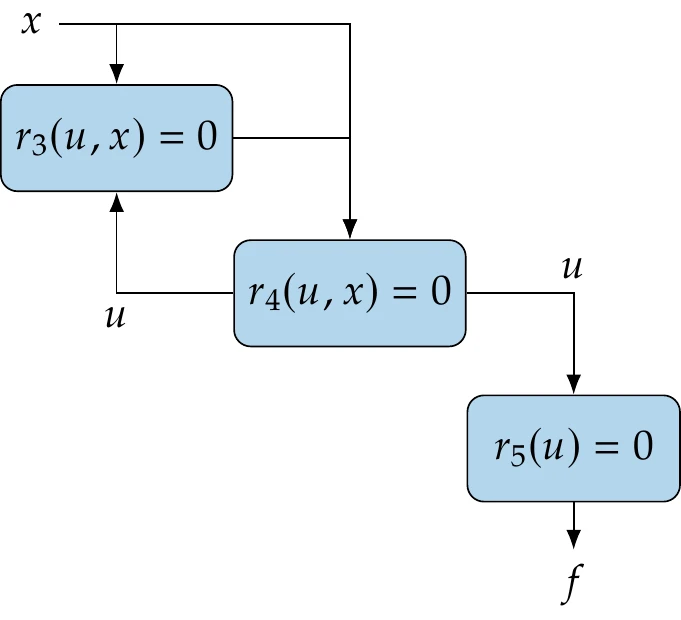

As mentioned in Chapter 3, a discretized numerical model can be written as a system of residuals,

where the semicolon denotes that the design variables are fixed when these equations are solved for the state variables . Through these equations, is an implicit function of . This relationship is represented by the box containing the solver and residual equations in Figure 6.25.

Figure 6.25:Relationship between functions and design variables for a system involving a solver. The implicit equations define the states for a given , so the functions of interest depend explicitly and implicitly on the design variables .

The functions of interest, , are typically explicit functions of the state variables and the design variables. However, because is an implicit function of , is ultimately an implicit function of as well. To compute for a given , we must first find such that . This is usually the most computationally costly step and requires a solver (see Section 3.6). The residual equations could be nonlinear and involve many state variables. In PDE-based models it is common to have millions of states. Once we have solved for the state variables , we can compute the functions of interest . The computation of for a given and is usually much cheaper because it does not require a solver. For example, in PDE-based models, computing such functions typically involves an integration of the states over a surface, or some other transformation of the states.

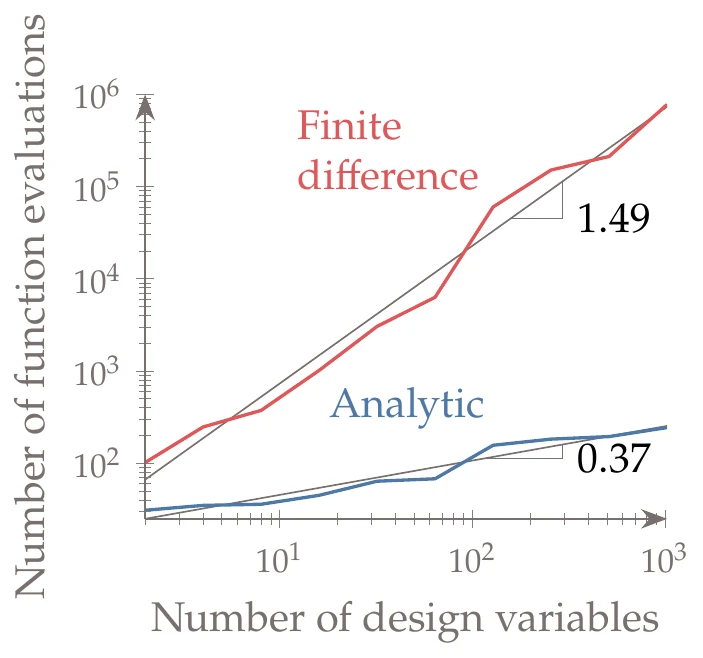

To compute using finite differences, we would have to use the solver to find for each perturbation of . That means that we would have to run the solver times, which would not scale well when the solution is costly. AD also requires the propagation of derivatives through the solution process. As we will see, implicit analytic methods avoid involving the potentially expensive nonlinear solution in the derivative computation.

Recall Example 3.2, where we introduced the structural model of a truss structure. The residuals in this case are the linear equations,

where the state variables are the displacements, . Solving for the displacement requires only a linear solver in this case, but it is still the most costly part of the analysis. Suppose that the design variables are the cross-sectional areas of the truss members. Then, the stiffness matrix is a function of , but the external forces are not.

Suppose that the functions of interest are the stresses in each of the truss members. This is an explicit function of the displacements, which is given by the matrix multiplication

where is a matrix that depends on . This is a much cheaper computation than solving the linear system (Equation 6.38).

6.7.2 Direct and Adjoint Derivative Equations¶

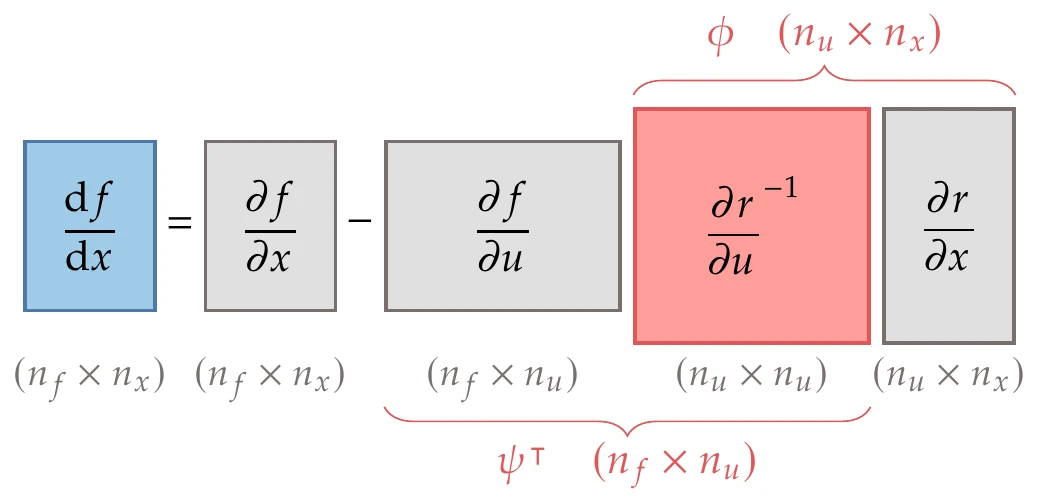

The derivatives we ultimately want to compute are the ones in the Jacobian . Given the explicit and implicit dependence of on , we can use the chain rule to write the total derivative Jacobian of as

where the result is an matrix.[10]In this context, the total derivatives, , take into account the change in that is required to keep the residuals of the governing equations (Equation 6.37) equal to zero. The partial derivatives in Equation 6.39 represent the variation of with respect to changes in or without regard to satisfying the governing equations.

To better understand the difference between total and partial derivatives in this context, imagine computing these derivatives using finite differences with small perturbations. For the total derivatives, we would perturb , re-solve the governing equations to obtain , and then compute , which would account for both dependency paths in Figure 6.25. To compute the partial derivatives and , however, we would perturb or and recompute without re-solving the governing equations. In general, these partial derivative terms are cheap to compute numerically or can be obtained symbolically.

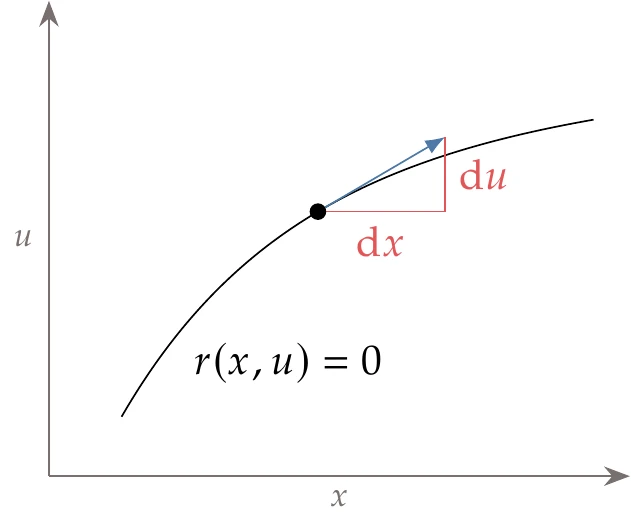

To find the total derivative , we need to consider the governing equations. Assuming that we are at a point where , any perturbation in must be accompanied by a perturbation in such that the governing equations remain satisfied. Therefore, the differential of the residuals can be written as

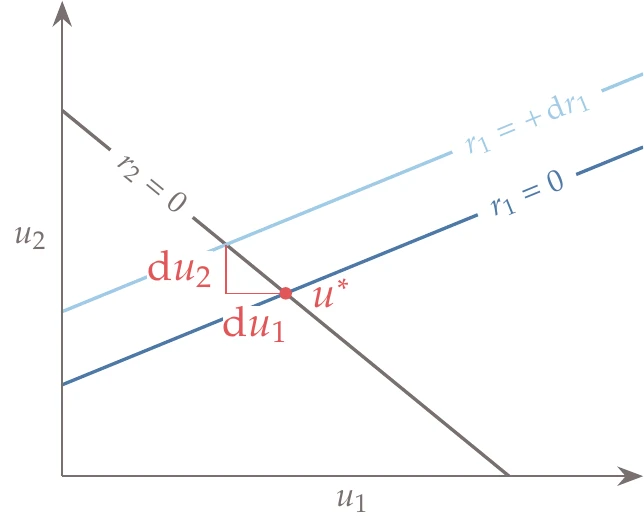

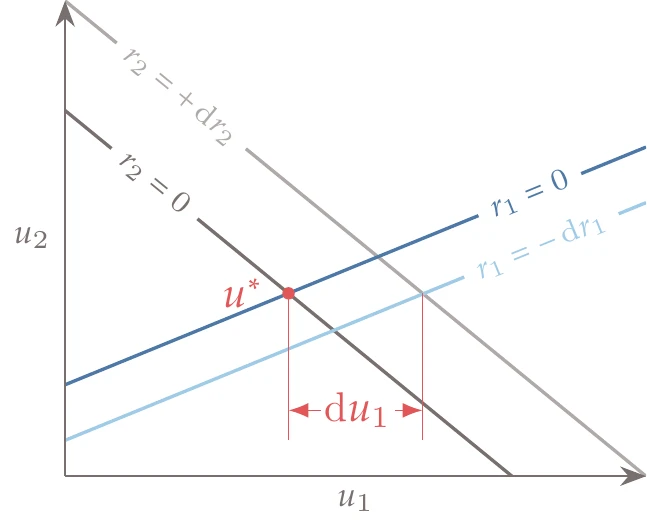

This constraint is illustrated in Figure 6.26 in two dimensions, but keep in mind that , , and are vectors in the general case.

The governing equations (Equation 6.37) map an -vector to an -vector . This mapping defines a hypersurface (also known as a manifold) in the – space.

The total derivative that we ultimately want to compute represents the effect that a perturbation on has on subject to the constraint of remaining on this hypersurface, which can be achieved with the appropriate variation in .

Figure 6.26:The governing equations determine the values of for a given . Given a point that satisfies the equations, the appropriate differential in must accompany a differential of about that point for the equations to remain satisfied.

To obtain a more useful equation, we rearrange Equation 6.40 to get the linear system

where and are both matrices, and is a square matrix of size . This linear system is useful because if we provide the partial derivatives in this equation (which are cheap to compute), we can solve for the total derivatives (whose computation would otherwise require re-solving ). Because is a matrix with columns, this linear system needs to be solved for each with the corresponding column of the right-hand-side matrix .

Now let us assume that we can invert the matrix in the linear system (Equation 6.41) and substitute the solution for into the total derivative equation (Equation 6.39). Then we get

where all the derivative terms on the right-hand side are partial derivatives. The partial derivatives in this equation can be computed using any of the methods that we have described earlier: symbolic differentiation, finite differences, complex step, or AD. Equation 6.42 shows two ways to compute the total derivatives, which we call the direct method and the adjoint method.

The direct method (already outlined earlier) consists of solving the linear system (Equation 6.41) and substituting into Equation 6.39. Defining , we can rewrite Equation 6.41 as

After solving for (one column at the time), we can use it in the total derivative equation (Equation 6.39) to obtain,

This is sometimes called the forward mode because it is analogous to forward-mode AD.

Solving the linear system (Equation 6.43) is typically the most computationally expensive operation in this procedure. The cost of this approach scales with the number of inputs but is essentially independent of the number of outputs . This is the same scaling behavior as finite differences and forward-mode AD. However, the constant of proportionality is typically much smaller in the direct method because we only need to solve the nonlinear equations once to obtain the states.

Figure 6.27:The total derivatives (Equation 6.42) can be computed either by solving for (direct method) or by solving for (adjoint method).

The adjoint method changes the linear system that is solved to compute the total derivatives. Looking at Figure 6.27, we see that instead of solving the linear system with on the right-hand side, we can solve it with on the right-hand side. This corresponds to replacing the two Jacobians in the middle with a new matrix of unknowns,

where the columns of are called the adjoint vectors. Multiplying both sides of Equation 6.45 by on the right and taking the transpose of the whole equation, we obtain the adjoint equation,

This linear system has no dependence on . Each adjoint vector is associated with a function of interest and is found by solving the adjoint equation (Equation 6.46) with the corresponding row . The solution () is then used to compute the total derivative

This is sometimes called the reverse mode because it is analogous to reverse-mode AD.

As we will see in Section 6.9, the adjoint vectors are equivalent to the total derivatives , which quantify the change in the function of interest given a perturbation in the residual that gets zeroed out by an appropriate change in .[11]

6.7.3 Direct or Adjoint?¶

Figure 6.28:Two possibilities for the size of in Figure 6.27. When , it is advantageous to solve the linear system with the vector to the right of the square matrix because it has fewer columns. When , it is advantageous to solve the transposed linear system with the vector to the left because it has fewer rows.

Similar to the direct method, the solution of the adjoint linear system (Equation 6.46) tends to be the most expensive operation. Although the linear system is of the same size as that of the direct method, the cost of the adjoint method scales with the number of outputs and is essentially independent of the number of inputs . The comparison between the computational cost of the direct and adjoint methods is summarized in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 6.28.

Similar to the trade-offs between forward- and reverse-mode AD, if the number of outputs is greater than the number of inputs, the direct (forward) method is more efficient (Figure 6.28, top). On the other hand, if the number of inputs is greater than the number of outputs, it is more efficient to use the adjoint (reverse) method (Figure 6.28, bottom). When the number of inputs and outputs is large and similar, neither method has an advantage, and the cost of computing the full total derivative Jacobian might be prohibitive. In this case, aggregating the outputs and using the adjoint method might be effective, as explained in Tip 6.7.

In practice, the adjoint method is implemented much more often than the direct method. Although both methods require a similar implementation effort, the direct method competes with methods that are much more easily implemented, such as finite differencing, complex step, and forward-mode AD. On the other hand, the adjoint method only competes with reverse-mode AD, which is plagued by the memory issue.

Table 3:Cost comparison of computing derivatives with direct and adjoint methods.

| Step | Direct | Adjoint |

| Partial derivative computation | Same | Same |

| Linear solution | times | times |

| Matrix multiplications | Same | Same |

Another reason why the adjoint method is more widely used is that many optimization problems have a few functions of interest (one objective and a few constraints) and many design variables. The adjoint method has made it possible to solve optimization problems involving computationally intensive PDE models.[12]

Although implementing implicit analytic methods is labor intensive, it is worthwhile if the differentiated code is used frequently and in applications that demand repeated evaluations. For such applications, analytic differentiation with partial derivatives computed using AD is the recommended approach for differentiating code because it combines the best features of these methods.

Consider the following simplified equation for the natural frequency of a beam:

where is a function of through the following relationship:

Figure 6.29 shows the equivalent of Figure 6.25 in this case. Our goal is to compute the derivative . Because is an implicit function of , we cannot find an explicit expression for as a function of , substitute that expression into Equation 6.48, and then differentiate normally. Fortunately, the implicit analytic methods allow us to compute this derivative.

Figure 6.29:Model for this example.

Referring back to our nomenclature,

where is the design variable and is the state variable. The partial derivatives that we need for the total derivative computation (Equation 6.42) are as follows:

Because this is a problem of only one function of interest and one design variable, there is no distinction between the direct and adjoint methods (forward and reverse), and the linear system solution is simply a division. Substituting these partial derivatives into the total derivative equation (Equation 6.42) yields

Thus, we obtained the desired derivative despite the implicitly defined function. Here, it was possible to get an explicit expression for the total derivative, but generally, it is only possible to get a numeric value.

Consider the structural analysis we reintroduced in Example 6.10. Let us compute the derivatives of the stresses with respect to the cross-sectional truss member areas and denote the number of degrees of freedom as and the number of truss members as . Figure 6.30 shows the equivalent of Figure 6.25 for this case.

Figure 6.30:Model for this example

We require four Jacobians of partial derivatives: , , , and . When differentiating the governing equations with respect to an area , neither the displacements nor the external forces depend directly on the areas,[13]so we obtain

This is a vector of size corresponding to one column of . We can compute this term by symbolically differentiating the equations that assemble the stiffness matrix. Alternatively, we could use AD on the function that computes the stiffness matrix or use finite differencing. Using AD, we can employ the techniques described in Section 6.7.4 for an efficient implementation.

It is more efficient to compute the derivative of the product directly instead of differentiating and then multiplying by . This avoids storing and subtracting the entire perturbed matrix. We can apply a forward finite difference to the product as follows:

Because the external forces do not depend on the displacements in this case,[14]the partial derivatives of the governing equations with respect to the displacements are given by

We already have the stiffness matrix, so this term does not require any further computations.

The partial derivative of the stresses with respect to the areas is zero () because there is no direct dependence.[15]Thus, the partial derivative of the stress with respect to displacements is

which is an matrix that we already have from the stress computation.

Now we can use either the direct or adjoint method by replacing the partial derivatives in the respective equations. The direct linear system (Equation 6.43) yields

where corresponds to each truss member area. Once we have , we can use it to compute the total derivatives of all the stresses with respect to member area with Equation 6.44, as follows:

The adjoint linear system (Equation 6.46) yields[16]

where corresponds to each truss member, and is the th row of . Once we have , we can use it to compute the total derivative of the stress in member with respect to all truss member areas with Equation 6.47, as follows:

In this case, there is no advantage in using one method over the other because the number of areas is the same as the number of stresses. However, if we aggregated the stresses as suggested in Tip 6.7, the adjoint would be advantageous.

For problems with many outputs and many inputs, there is no efficient way of computing the Jacobian. This is common in some structural optimization problems, where the number of stress constraints is similar to the number of design variables because they are both associated with each structural element (see Example 6.12).

We can address this issue by aggregating the functions of interest as described in Section 5.7 and then implementing the adjoint method to compute the gradient. In Example 6.12, we would aggregate the stresses in one or more groups to reduce the number of required adjoint solutions.

We can use these techniques to aggregate any outputs, but in principle, these outputs should have some relation to each other. For example, they could be the stresses in a structure (see Example 6.12).[17]

6.7.4 Adjoint Method with AD Partial Derivatives¶

Implementing the implicit analytic methods for models involving long, complicated code requires significant development effort. In this section, we focus on implementing the adjoint method because it is more widely used, as explained in Section 6.7.3. We assume that , so that the adjoint method is advantageous.

To ease the implementation of adjoint methods, we recommend a hybrid adjoint approach where the reverse mode of AD computes the partial derivatives in the adjoint equations (Equation 6.46) and total derivative equation (Equation 6.47).[18]

The partials terms form an matrix and is an matrix. These partial derivatives can be computed by identifying the section of the code that computes for a given and and running the AD tool for that section. This produces code that takes as an input and outputs and , as shown in Figure 6.31.

Figure 6.31:Applying reverse AD to the code that computes produces code that computes the partial derivatives of with respect to and .

Recall that we must first run the entire original code that computes and . Then we can run the AD code with the desired seed. Suppose we want the derivative of the th component of . We would set and the other elements to zero. After running the AD code, we obtain and , which correspond to the rows of the respective matrix of partial terms, that is,

Thus, with each run of the AD code, we obtain the derivatives of one function with respect to all design variables and all state variables. One run is required for each element of . The reverse mode is advantageous if , .

The Jacobian can also be computed using AD. Because is typically sparse, the techniques covered in Section 6.8 significantly increase the efficiency of computing this matrix. This is a square matrix, so neither AD mode has an advantage over the other if we explicitly compute and store the whole matrix.

However, reverse-mode AD is advantageous when using an iterative method to solve the adjoint linear system (Equation 6.46). When using an iterative method, we do not form . Instead, we require products of the transpose of this matrix with some vector ,[19]

The elements of act as weights on the residuals and can be interpreted as a projection onto the direction of . Suppose we have the reverse AD code for the residual computation, as shown in Figure 6.32.

Figure 6.32:Applying reverse AD to the code that computes produces code that computes the partial derivatives of with respect to and .

This code requires a reverse seed , which determines the weights we want on each residual. Typically, a seed would have only one nonzero entry to find partial derivatives (e.g., setting would yield the first row of the Jacobian, ). However, to get the product in Equation 6.50, we require the seed to be weighted as . Then, we can compute the product by running the reverse AD code once to obtain .

The final term needed to compute total derivatives with the adjoint method is the last term in Equation 6.47, which can be written as

This is yet another transpose vector product that can be obtained using the same reverse AD code for the residuals, except that now the residual seed is , and the product we want is given by .

In sum, it is advantageous to use reverse-mode AD to compute the partial derivative terms for the adjoint equations, especially if the adjoint equations are solved using an iterative approach that requires only matrix-vector products. Similar techniques and arguments apply for the direct method, except that in that case, forward-mode AD is advantageous for computing the partial derivatives.

Always compare your derivative computation against a different implementation.

You can compare analytic derivatives with finite-difference derivatives, but that is only a partial verification because finite differences are not accurate enough. Comparing against the complex-step method or AD is preferable. Still, finite differences are recommended as an additional check. If you can only use finite differences, compare two different finite difference approximations.

You should use unit tests to verify each partial derivative term as you are developing the code (see Tip 3.4) instead of just hoping it all works together at the end (it usually does not!). One necessary but not sufficient test for the verification of analytic methods is the dot-product test. For analytic methods, the dot-product test can be derived from Equation 6.42. For a chosen variable and function , we have the following equality:

Each side of this equation yields a scalar that should match to working precision. The dot-product test verifies that your partial derivatives and the solutions for the direct and adjoint linear systems are consistent.

For AD, the dot-product test for a code with inputs and outputs is as follows:

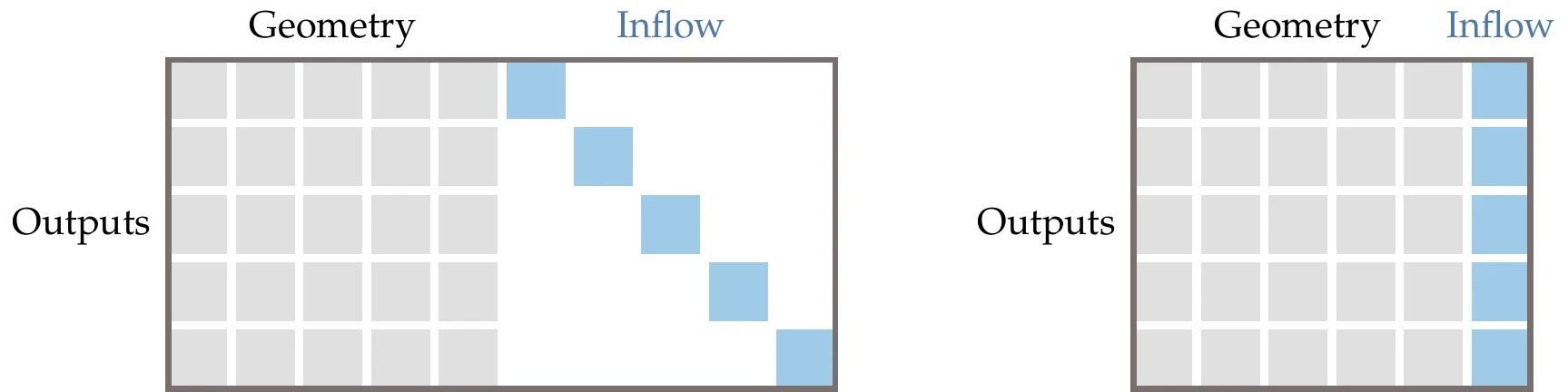

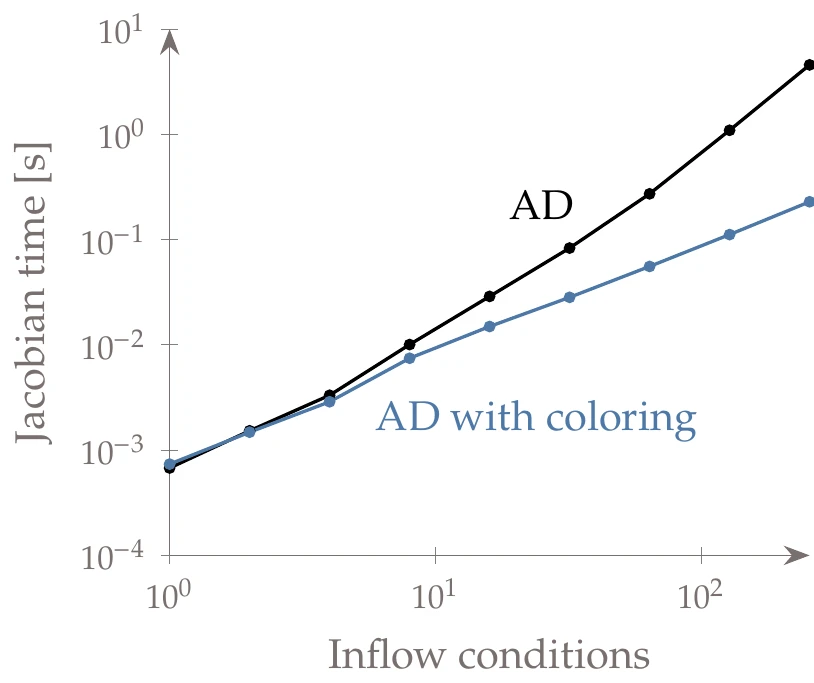

6.8 Sparse Jacobians and Graph Coloring¶

In this chapter, we have discussed various ways to compute a Jacobian of a model. If the Jacobian has many zero elements, it is said to be sparse. In many cases, we can take advantage of that sparsity to significantly reduce the computational time required to construct the Jacobian.

When applying a forward approach (forward-mode AD, finite differencing, or complex step), the cost of computing the Jacobian scales with . Each forward pass re-evaluates the model to compute one column of the Jacobian. For example, when using finite differencing, evaluations would be required. To compute the th column of the Jacobian, the input vector would be

We can significantly reduce the cost of computing the Jacobian depending on its sparsity pattern. As a simple example, consider a square diagonal Jacobian:

For this scenario, the Jacobian can be constructed with one evaluation rather than evaluations. This is because a given output depends on only one input . We could think of the outputs as independent functions. Thus, for finite differencing, rather than requiring input vectors with function evaluations, we can use one input vector, as follows:

allowing us to compute all the nonzero entries in one pass.[20]

Although the diagonal case is easy to understand, it is a special situation. To generalize this concept, let us consider the following matrix as an example:

A subset of columns that does not have more than one nonzero in any given row are said to be structurally orthogonal. In this example, the following sets of columns are structurally orthogonal: (1, 3), (1, 5), (2, 3), (2, 4, 5), (2, 6), and (4, 5). Structurally orthogonal columns can be combined, forming a smaller Jacobian that reduces the number of forward passes required. This reduced Jacobian is referred to as compressed. There is more than one way to compress this Jacobian, but in this case, the minimum number of compressed columns—referred to as colors—is three. In the following compressed Jacobian, we combine columns 1 and 3 (blue); columns 2, 4, and 5 (red); and leave column 6 on its own (black):

For finite differencing, complex step, and forward-mode AD, only compression among columns is possible. Reverse mode AD allows compression among the rows. The concept is the same, but instead, we look for structurally orthogonal rows. One such compression is as follows:

AD can also be used even more flexibly when both modes are used: forward passes to evaluate groups of structurally orthogonal columns and reverse passes to evaluate groups of structurally orthogonal rows. Rather than taking incremental steps in each direction as is done in finite differencing, we set the AD seed vector with 1s in the directions we wish to evaluate, similar to how the seed is set for directional derivatives, as discussed in Section 6.6.