5 Constrained Gradient-Based Optimization

Engineering design optimization problems are rarely unconstrained. In this chapter, we explain how to solve constrained problems. The methods in this chapter build on the gradient-based unconstrained methods from Chapter 4 and also assume smooth functions. We first introduce the optimality conditions for a constrained optimization problem and then focus on three main methods for handling constraints: penalty methods, sequential quadratic programming (SQP), and interior-point methods.

Penalty methods are no longer used in constrained gradient-based optimization because they have been replaced by more effective methods. Still, the concept of a penalty is useful when thinking about constraints, partially motivates more sophisticated approaches like interior-point methods, and is often used with gradient-free optimizers.

SQP and interior-point methods represent the state of the art in nonlinear constrained optimization. We introduce the basics for these two optimization methods, but a complete and robust implementation of these methods requires detailed knowledge of a growing body of literature that is not covered here.

5.1 Constrained Problem Formulation¶

We can express a general constrained optimization problem as

where is the vector of inequality constraints, is the vector of equality constraints, and and are lower and upper design variable bounds (also known as bound constraints). Both objective and constraint functions can be nonlinear, but they should be continuous to be solved using gradient-based optimization algorithms. The inequality constraints are expressed as “less than” without loss of generality because they can always be converted to “greater than” by putting a negative sign on . We could also eliminate the equality constraints without loss of generality by replacing it with two inequality constraints, and , where is some small number. In practice, it is desirable to distinguish between equality and inequality constraints because of numerical precision and algorithm implementation.

The constrained problem formulation just described does not distinguish between nonlinear and linear constraints. It is advantageous to make this distinction because some algorithms can take advantage of these differences. However, the methods introduced in this chapter assume general nonlinear functions.

For unconstrained gradient-based optimization (Chapter 4), we only require the gradient of the objective, . To solve a constrained problem, we also require the gradients of all the constraints. Because the constraints are vectors, their derivatives yield a Jacobian matrix. For the equality constraints, the Jacobian is defined as

which is an matrix whose rows are the gradients of each constraint. Similarly, the Jacobian of the inequality constraints is an matrix.

5.2 Understanding n-Dimensional Space¶

Understanding the optimality conditions and optimization algorithms for constrained problems requires basic -dimensional geometry and linear algebra concepts. Here, we review the concepts in an informal way.[1] We sketch the concepts for two and three dimensions to provide some geometric intuition but keep in mind that the only way to tackle dimensions is through mathematics.

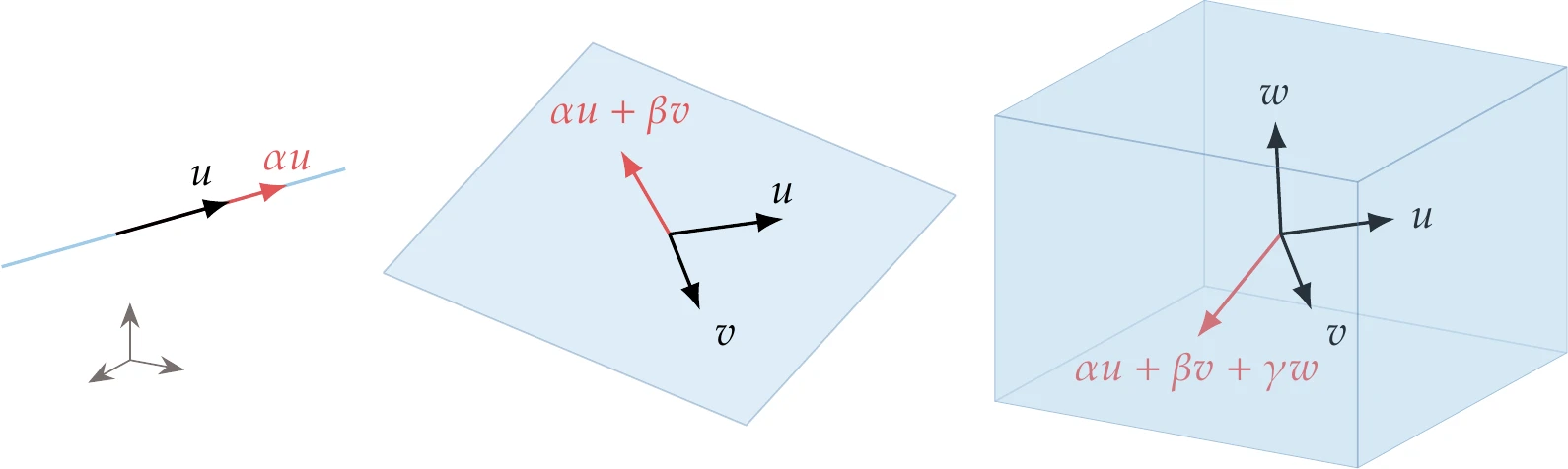

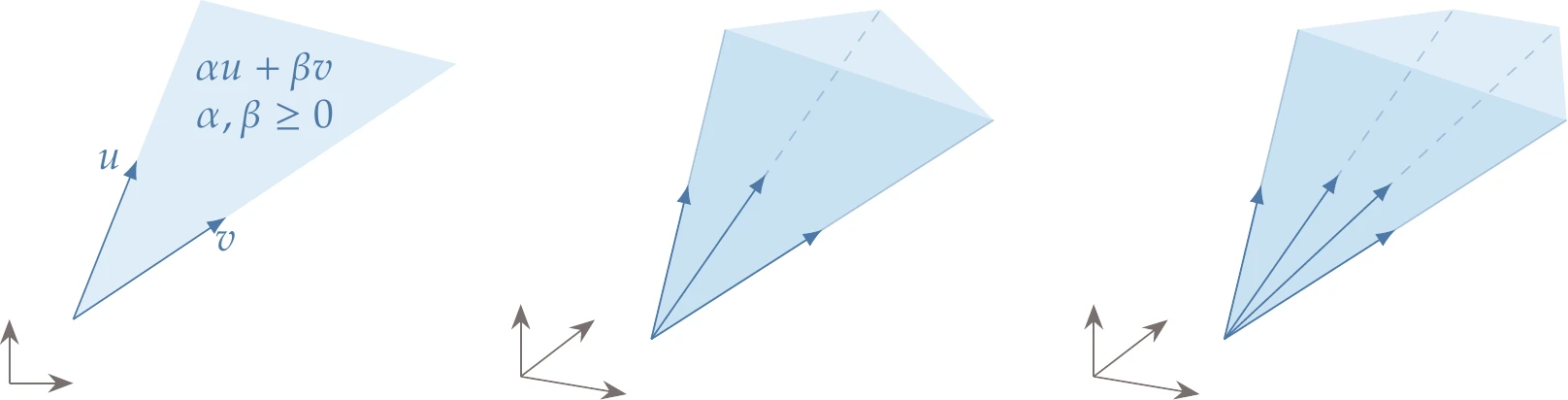

There are several essential linear algebra concepts for constrained optimization. The span of a set of vectors is the space formed by all the points that can be obtained by a linear combination of those vectors. With one vector, this space is a line, with two linearly independent vectors, this space is a two-dimensional plane (see Figure 5.2), and so on. With linearly independent vectors, we can obtain any point in -dimensional space.

Figure 5.2:Span of one, two, and three vectors in three-dimensional space.

Because matrices are composed of vectors, we can apply the concept of span to matrices. Suppose we have a rectangular matrix . For our purposes, we are interested in considering the row vectors in the matrix.

The rank of is the number of linearly independent rows of , and it corresponds to the dimension of the space spanned by the row vectors of .

The nullspace of a matrix is the set of all -dimensional vectors such that .

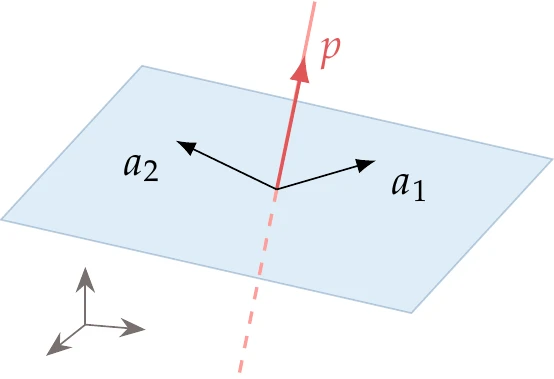

Figure 5.3:Nullspace of a matrix of rank 2, where and are the row vectors of .

This is a subspace of dimensions, where is the rank of . One fundamental theorem of linear algebra is that the nullspace of a matrix contains all the vectors that are perpendicular to the row space of that matrix and vice versa. This concept is illustrated in Figure 5.3 for , where , leaving only one dimension for the nullspace. Any vector that is perpendicular to must be a linear combination of the rows of , so it can be expressed as .[2]A hyperplane is a generalization of a plane in -dimensional space and is an essential concept in constrained optimization. In a space of dimensions, a hyperplane is a subspace with at most dimensions. In Figure 5.4, we illustrate hyperplanes in two dimensions (a line) and three dimensions (a two-dimensional plane); higher dimensions cannot be visualized, but the mathematical description that follows holds for any .

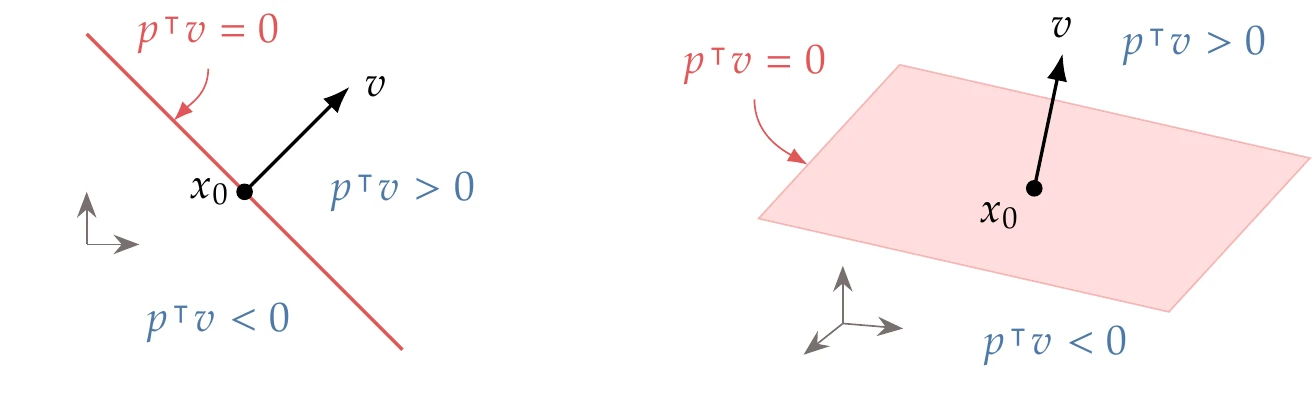

Figure 5.4:Hyperplanes and half-spaces in two and three dimensions.

To define a hyperplane of dimensions, we just need a point contained in the hyperplane () and a vector (). Then, the hyperplane is defined as the set of all points such that . That is, the hyperplane is defined by all vectors that are perpendicular to . To define a hyperplane with dimensions, we would need two vectors, and so on. In dimensions, a hyperplane of dimensions divides the space into two half-spaces: in one of these, , and in the other, . Each half-space is closed if it includes the hyperplane () and open otherwise.

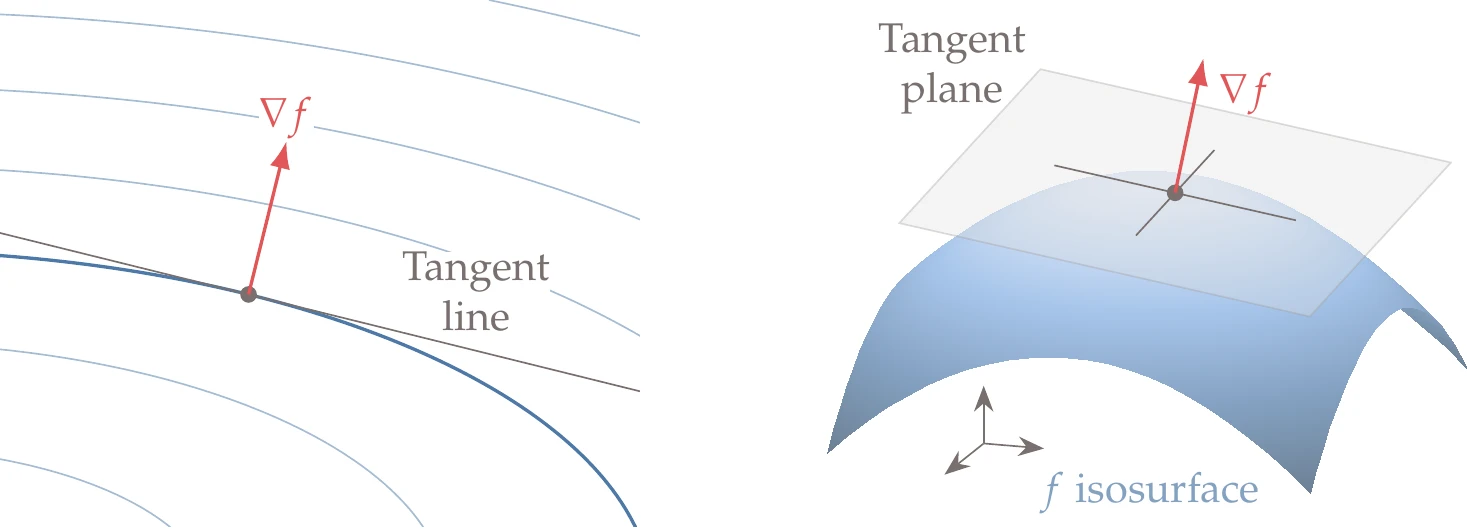

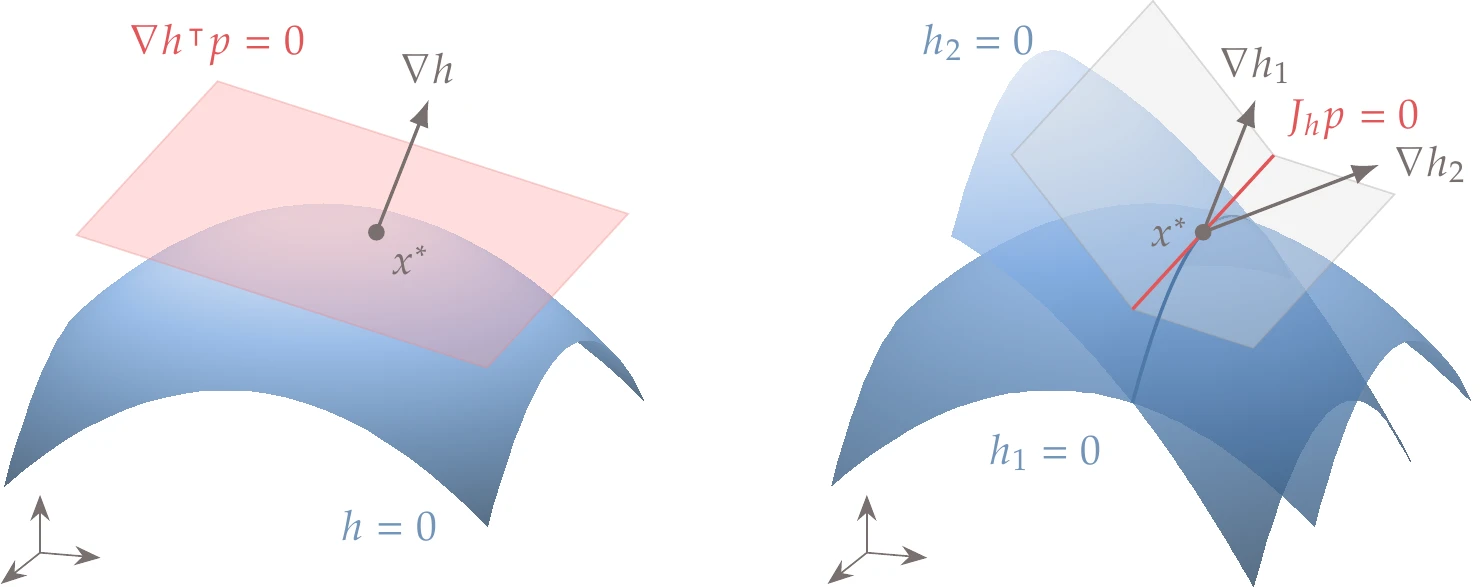

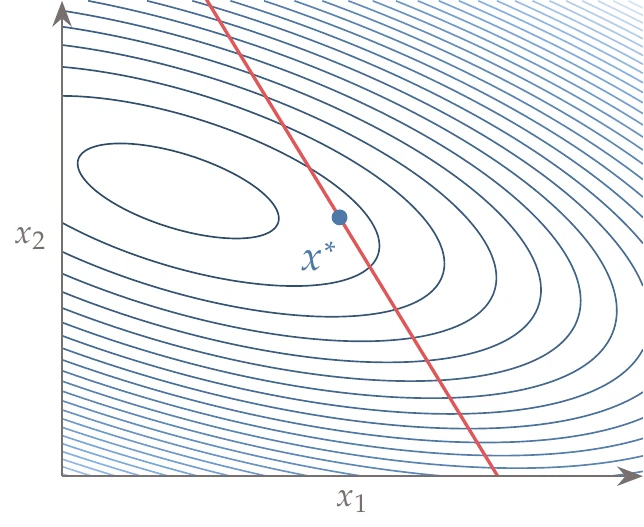

When we have the isosurface of a function , the function gradient at a point on the isosurface is locally perpendicular to the isosurface. The gradient vector defines the tangent hyperplane at that point, which is the set of points such that . In two dimensions, the isosurface reduces to a contour and the tangent reduces to a line, as shown in Figure 5.5 (left). In three dimensions, we have a two-dimensional hyperplane tangent to an isosurface, as shown in Figure 5.5 (right).

Figure 5.5:The gradient of a function defines the hyperplane tangent to the function isosurface.

The intersection of multiple half-spaces yields a polyhedral cone.

A polyhedral cone is the set of all the points that can be obtained by the linear combination of a given set of vectors using nonnegative coefficients. This concept is illustrated in Figure 5.6 (left) for the two-dimensional case.

In this case, only two vectors are required to define a cone uniquely. In three dimensions and higher there could be any number of vectors corresponding to all the possible polyhedral “cross sections”, as illustrated in Figure 5.6 (middle and right).

Figure 5.6:Polyhedral cones in two and three dimensions.

5.3 Optimality Conditions¶

The optimality conditions for constrained optimization problems are not as straightforward as those for unconstrained optimization (Section 4.1.4). We begin with equality constraints because the mathematics and intuition are simpler, then add inequality constraints. As in the case of unconstrained optimization, the optimality conditions for constrained problems are used not only for the termination criteria, but they are also used as the basis for optimization algorithms.

5.3.1 Equality Constraints¶

First, we review the optimality conditions for an unconstrained problem, which we derived in Section 4.1.4. For the unconstrained case, we can take a first-order Taylor series expansion of the objective function with some step that is small enough that the second-order term is negligible and write

If is a minimum point, then every point in a small neighborhood must have a greater value,

Given the Taylor series expansion (Equation 5.3), the only way that this inequality can be satisfied is if

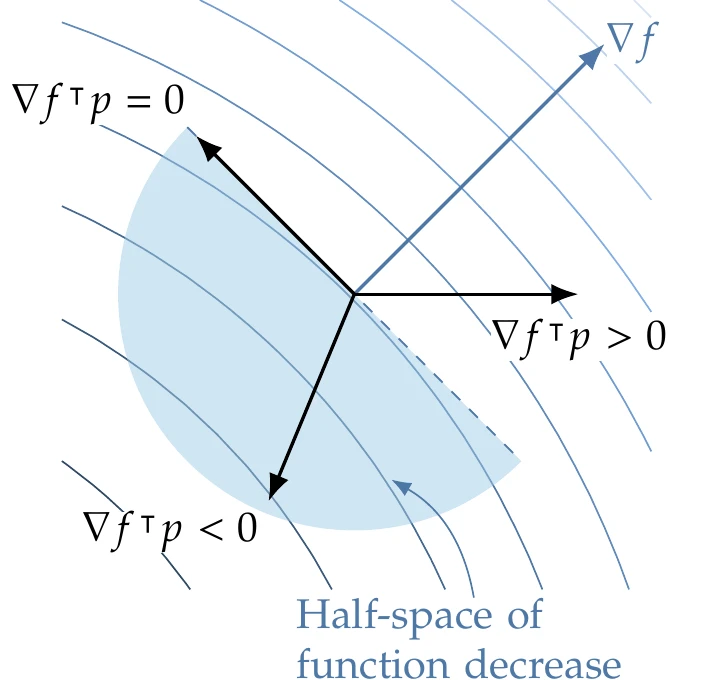

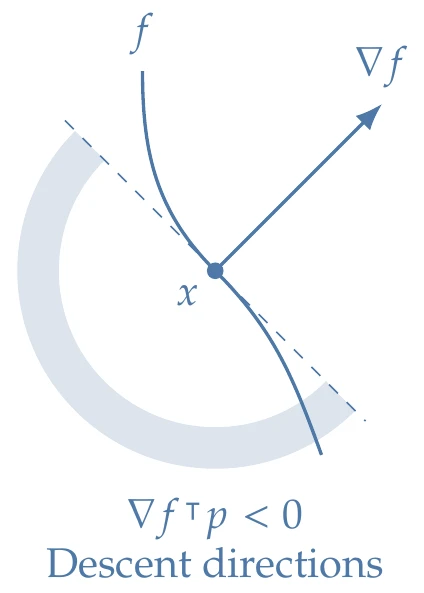

The condition defines a hyperplane that contains the directions along which the first-order variation of the function is zero. This hyperplane divides the space into an open half-space of directions where the function decreases () and an open half-space where the function increases (), as shown in Figure 5.7. Again, we are considering first-order variations.

Figure 5.7:The gradient , which is the direction of steepest function increase, splits the design space into two halves. Here we highlight the open half-space of directions that result in function decrease.

If the problem were unconstrained, the only way to satisfy the inequality in Equation 5.5 would be if . That is because for any nonzero , there is an open half-space of directions that result in a function decrease (see Figure 5.7). This is consistent with the first-order unconstrained optimality conditions derived in Section 4.1.4.

However, we now have a constrained problem. The function increase condition (Equation 5.5) still applies, but must also be a feasible direction. To find the feasible directions, we can write a first-order Taylor series expansion for each equality constraint function as

Again, the step size is assumed to be small enough so that the higher-order terms are negligible.

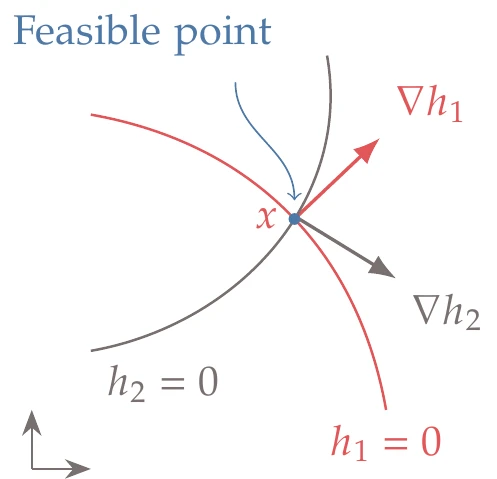

Assuming that is a feasible point, then for all constraints , and we are left with the second term in the linearized constraint (Equation 5.6). To remain feasible a small step away from , we require that for all . Therefore, first-order feasibility requires that

which means that a direction is feasible when it is orthogonal to all equality constraint gradients. We can write this in matrix form as

This equation states that any feasible direction has to lie in the nullspace of the Jacobian of the constraints, .

Figure 5.8:If we have two equality constraints () in two-dimensional space (), we are left with no freedom for optimization.

Assuming that has full row rank (i.e., the constraint gradients are linearly independent), then the feasible space is a subspace of dimension . For optimization to be possible, we require . Figure 5.8 illustrates a case where , where the feasible space reduces to a single point, and there is no freedom for performing optimization.

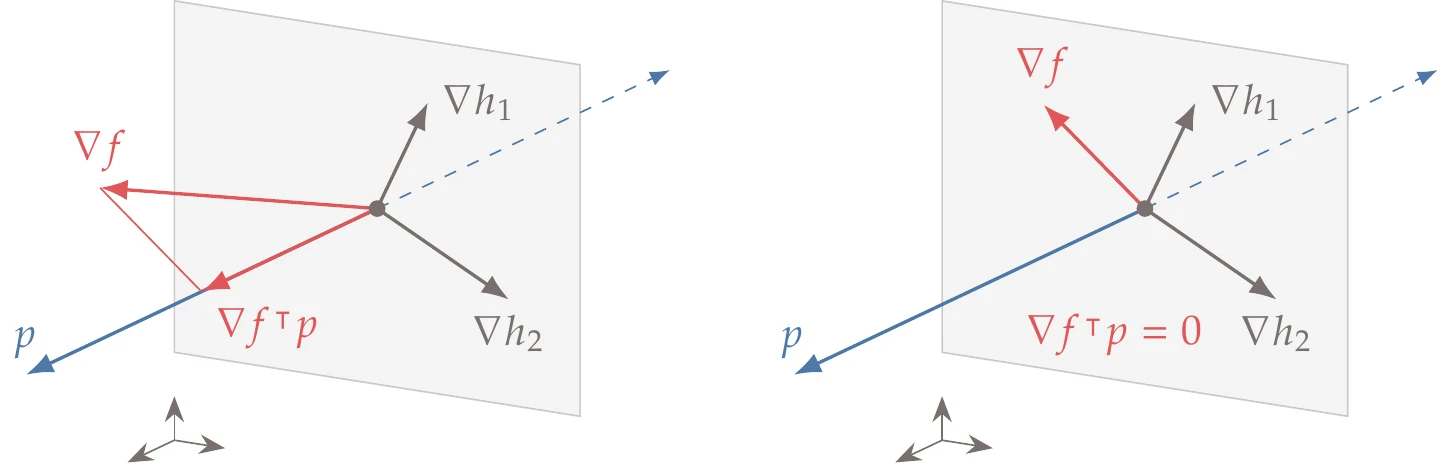

For one constraint, Equation 5.8 reduces to a dot product, and the feasible space corresponds to a tangent hyperplane, as illustrated on the left side of Figure 5.9 for the three-dimensional case. For two or more constraints, the feasible space corresponds to the intersection of all the tangent hyperplanes. On the right side of Figure 5.9, we show the intersection of two tangent hyperplanes in three-dimensional space (a line).

Figure 5.9:Feasible spaces in three dimensions for one and two constraints.

For constrained optimality, we need to satisfy both (Equation 5.5) and (Equation 5.8). For equality constraints, if a direction is feasible, then must also be feasible. Therefore, the only way to satisfy is if .

In sum, for to be a constrained optimum, we require

In other words, the projection of the objective function gradient onto the feasible space must vanish. Figure 5.10 illustrates this requirement for a case with two constraints in three dimensions.

Figure 5.10:If the projection of onto the feasible space is nonzero, there is a feasible descent direction (left); if the projection is zero, the point is a constrained optimum (right).

The constrained optimum conditions (Equation 5.9) require that be orthogonal to the nullspace of (since , as defined, is the nullspace of ). The row space of a matrix contains all the vectors that are orthogonal to its nullspace.[3]Because the rows of are the gradients of the constraints, the objective function gradient must be a linear combination of the gradients of the constraints. Thus, we can write the requirements defined in Equation 5.9 as a single vector equation,

where are called the Lagrange multipliers.[4]There is a multiplier associated with each constraint. The sign of the Lagrange multipliers is arbitrary for equality constraints but will be significant later when dealing with inequality constraints.

Therefore, the first-order optimality conditions for the equality constrained case are

where we have reexpressed Equation 5.10 in matrix form and added the constraint satisfaction condition.

In constrained optimization, it is sometimes convenient to use the Lagrangian function, which is a scalar function defined as

In this function, the Lagrange multipliers are considered to be independent variables. Taking the gradient of with respect to both and and setting them to zero yields

which are the first-order conditions derived in Equation 5.11.

With the Lagrangian function, we have transformed a constrained problem into an unconstrained problem by adding new variables, . A constrained problem of design variables and equality constraints was transformed into an unconstrained problem with variables. Although you might be tempted to simply use the algorithms of Chapter 4 to minimize the Lagrangian function (Equation 5.12), some modifications are needed in the algorithms to solve these problems effectively (particularly once inequality constraints are introduced).

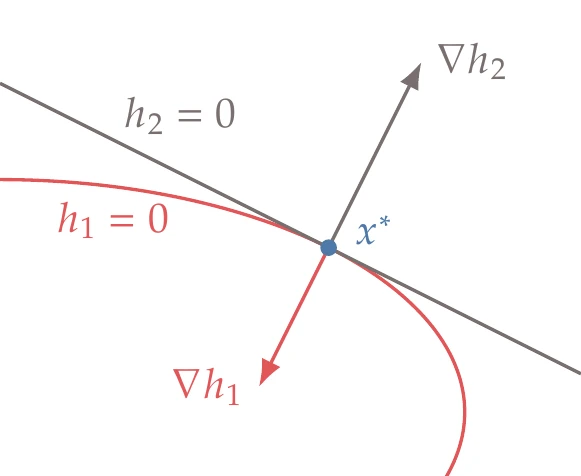

Figure 5.11:The constraint qualification condition does not hold in this case because the gradients of the two constraints not linearly independent.

The derivation of the first-order optimality conditions (Equation 5.11) assumes that the gradients of the constraints are linearly independent; that is, has full row rank. A point satisfying this condition is called a regular point and is said to satisfy linear independence constraint qualification. Figure 5.11 illustrates a case where the is not a regular point. A special case that does not satisfy constraint qualification is when one (or more) constraint gradient is zero. In that case, that constraint is not linearly independent, and the point is not regular. Fortunately, these situations are uncommon.

The optimality conditions just described are first-order conditions that are necessary but not sufficient. To make sure that a point is a constrained minimum, we also need to satisfy second-order conditions. For the unconstrained case, the Hessian of the objective function has to be positive definite. In the constrained case, we need to check the Hessian of the Lagrangian with respect to the design variables in the space of feasible directions. The Lagrangian Hessian is

where is the Hessian of the objective, and is the Hessian of equality constraint . The second-order sufficient conditions are as follows:

This ensures that the curvature of the Lagrangian is positive when projected onto any feasible direction.

5.3.2 Inequality Constraints¶

We can reuse some of the concepts from the equality constrained optimality conditions for inequality constrained problems.

Recall that an inequality constraint is feasible when and it is said to be active if and inactive if .

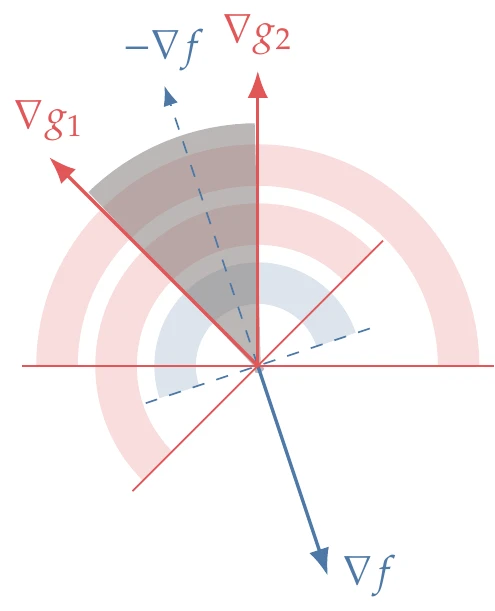

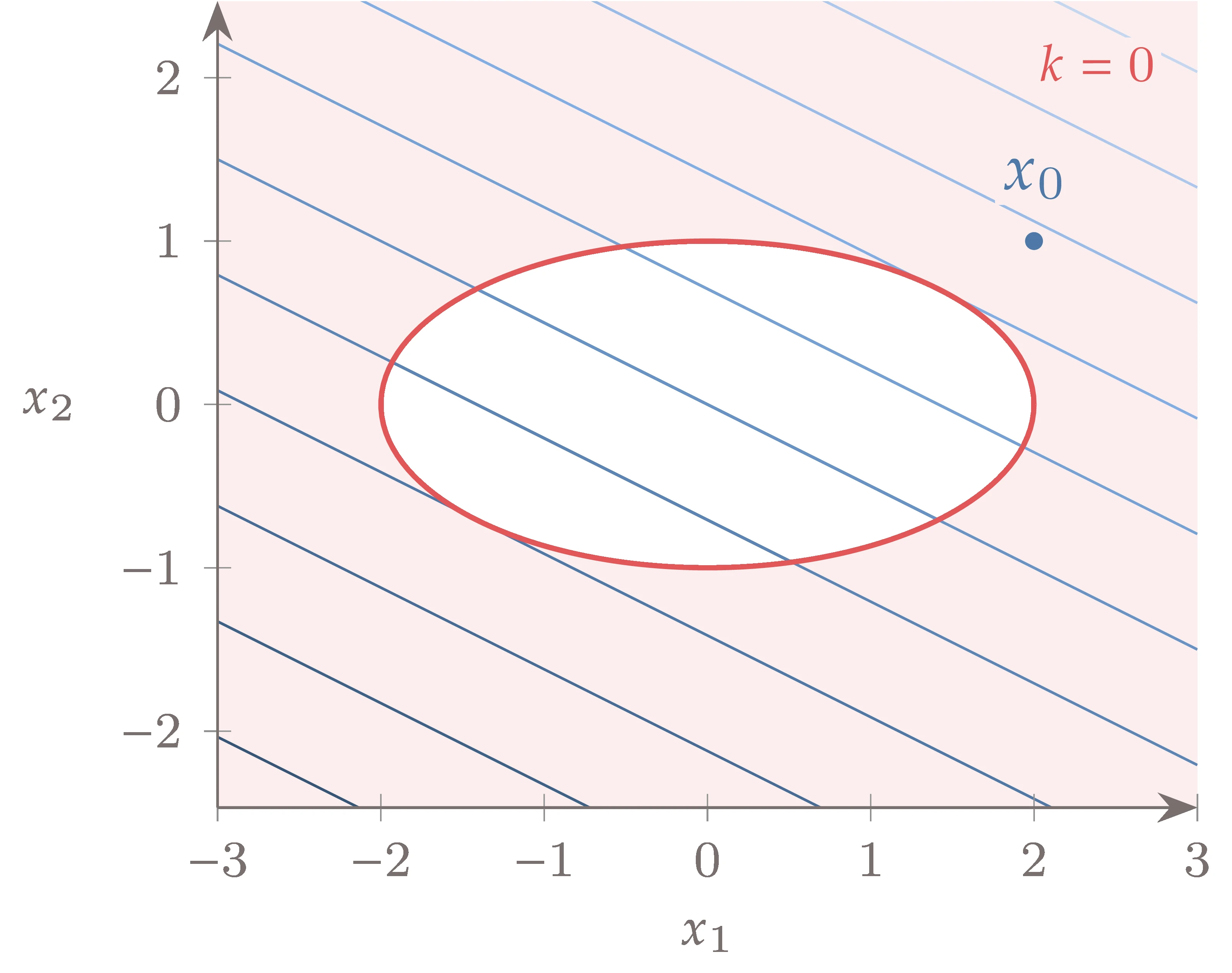

Figure 5.15:The descent directions are in the open half-space defined by the objective function gradient.

As before, if is an optimum, any small enough feasible step from the optimum must result in a function increase. Based on the Taylor series expansion (Equation 5.3), we get the condition

which is the same as for the equality constrained case. We use the arc in Figure 5.15 to show the descent directions, which are in the open half-space defined by the hyperplane tangent to the gradient of the objective.

To consider inequality constraints, we use the same linearization as the equality constraints (Equation 5.6), but now we enforce an inequality to get

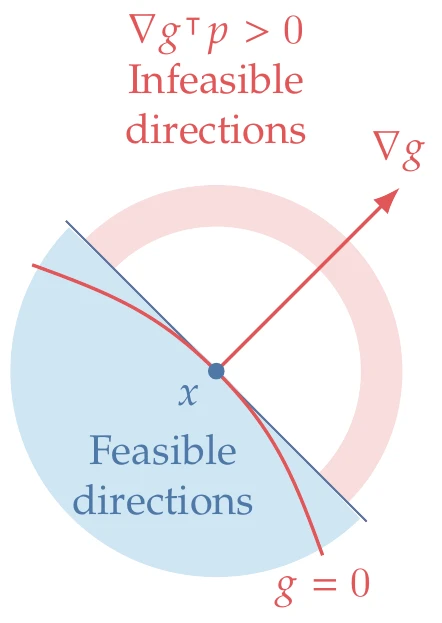

For a given candidate point that satisfies all constraints, there are two possibilities to consider for each inequality constraint: whether the constraint is inactive () or active (). If a given constraint is inactive, we do not need to add any condition for it because we can take a step in any direction and remain feasible as long as the step is small enough. Thus, we only need to consider the active constraints for the optimality conditions.

Figure 5.16:The feasible directions for each constraint are in the closed half-space defined by the inequality constraint gradient.

For the equality constraint, we found that all first-order feasible directions are in the nullspace of the Jacobian matrix. Inequality constraints are not as restrictive. From Equation 5.17, if constraint is active (), then the nearby point is only feasible if for all constraints that are active. In matrix form, we can write , where the Jacobian matrix includes only the gradients of the active constraints. Thus, the feasible directions for inequality constraint can be any direction in the closed half-space, corresponding to all directions such that , as shown in Figure 5.16. In this figure, the arc shows the infeasible directions.

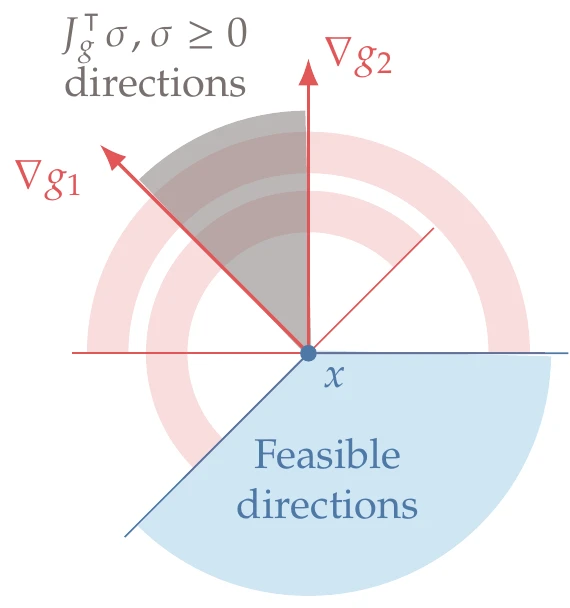

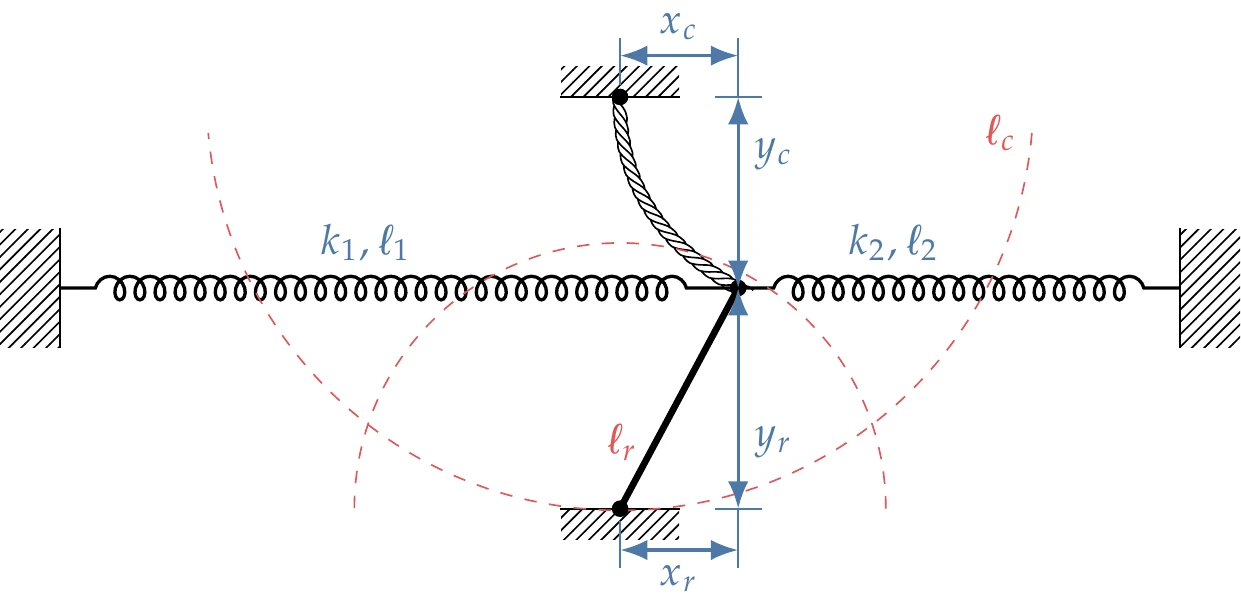

The set of feasible directions that satisfies all active constraints is the intersection of all the closed half-spaces defined by the inequality constraints, that is, all such that . This intersection of the feasible directions forms a polyhedral cone, as illustrated in Figure 5.17 for a two-dimensional case with two constraints.

Figure 5.17:Excluding the infeasible directions with respect to each constraint (red arcs) leaves the cone of feasible directions (blue), which is the polar cone of the active constraint gradients cone (gray).

To find the cone of feasible directions, let us first consider the cone formed by the active inequality constraint gradients (shown in gray in Figure 5.17). This cone is defined by all vectors such that

A direction is feasible if for all in the cone. The set of all feasible directions forms the polar cone of the cone defined by Equation 5.18 and is shown in blue in Figure 5.17.

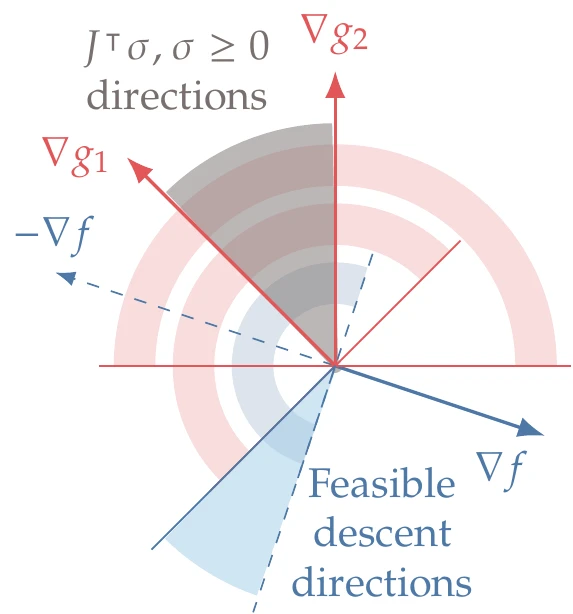

Now that we have established some intuition about the feasible directions, we need to establish under which conditions there is no feasible descent direction (i.e., we have reached an optimum). In other words, when is there no intersection between the cone of feasible directions and the open half-space of descent directions? To answer this question, we can use Farkas’ lemma. This lemma states that given a rectangular matrix ( in our case) and a vector with the same size as the rows of the matrix ( in our case), one (and only one) of two possibilities occurs:[7]

There exists a such that and . This means that there is a descent direction that is feasible (Figure 5.18, left).

There exists a such that with (Figure 5.18, right). This corresponds to optimality because it excludes the first possibility.

Figure 5.18:Two possibilities involving active inequality constraints.

The second possibility yields the following optimality criterion for inequality constraints:

Comparing with the corresponding criteria for equality constraints (Equation 5.13), we see a similar form. However, corresponds to the Lagrange multipliers for the inequality constraints and carries the additional restriction that .

If equality constraints are present, the conditions for the inequality constraints apply only in the subspace of the directions feasible with respect to the equality constraints.

Similar to the equality constrained case, we can construct a Lagrangian function whose stationary points are candidates for optimal points. We need to include all inequality constraints in the optimality conditions because we do not know in advance which constraints are active. To represent inequality constraints in the Lagrangian, we replace them with the equality constraints defined by

where is a new unknown associated with each inequality constraint called a slack variable. The slack variable is squared to ensure it is nonnegative In that way, Equation 5.20 can only be satisfied when is feasible ().

The significance of the slack variable is that when , the corresponding inequality constraint is active (), and when , the corresponding constraint is inactive.

The Lagrangian including both equality and inequality constraints is then

where represents the Lagrange multipliers associated with the inequality constraints. Here, we use to represent the element-wise multiplication of .[8]Similar to the equality constrained case, we seek a stationary point for the Lagrangian, but now we have additional unknowns: the inequality Lagrange multipliers and the slack variables. Taking partial derivatives of the Lagrangian with respect to each set of unknowns and setting those derivatives to zero yields the first-order optimality conditions:

This criterion is the same as before but with additional Lagrange multipliers and constraints. Taking the derivatives with respect to the equality Lagrange multipliers, we have

which enforces the equality constraints as before. Taking derivatives with respect to the inequality Lagrange multipliers, we get

which enforces the inequality constraints. Finally, differentiating the Lagrangian with respect to the slack variables, we obtain

which is called the complementary slackness condition. This condition helps us to distinguish the active constraints from the inactive ones. For each inequality constraint, either the Lagrange multiplier is zero (which means that the constraint is inactive), or the slack variable is zero (which means that the constraint is active). Unfortunately, the complementary slackness condition introduces a combinatorial problem. The complexity of this problem grows exponentially with the number of inequality constraints because the number of possible combinations of active versus inactive constraints is .

In addition to the conditions for a stationary point of the Lagrangian (Equation 5.22, Equation 5.23, Equation 5.24, and Equation 5.25), recall that we require the Lagrange multipliers for the active constraints to be nonnegative. Putting all these conditions together in matrix form, the first-order constrained optimality conditions are as follows:

These are called the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions. The equality and inequality constraints are sometimes lumped together using a single Jacobian matrix (and single Lagrange multiplier vector). This can be convenient because the expression for the Lagrangian follows the same form for both cases.

As in the equality constrained case, these first-order conditions are necessary but not sufficient. The second-order sufficient conditions require that the Hessian of the Lagrangian must be positive definite in all feasible directions, that is,

In other words, we only require positive definiteness in the intersection of the nullspace of the equality constraint Jacobian with the feasibility cone of the active inequality constraints.

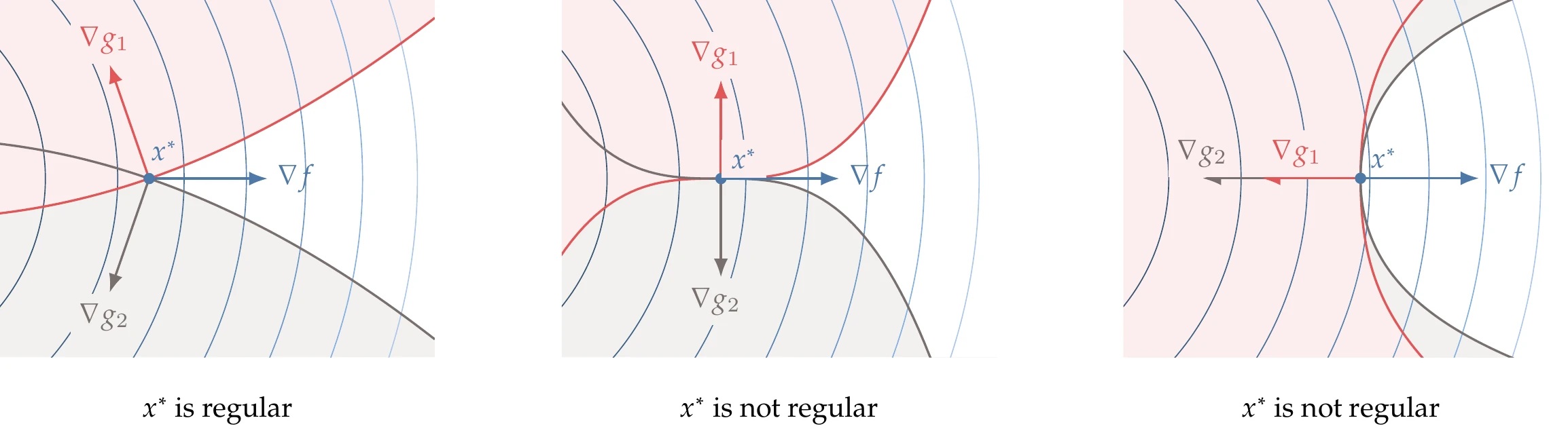

Similar to the equality constrained case, the KKT conditions (Equation 5.26) only apply when a point is regular, that is, when it satisfies linear independence constraint qualification. However, the linear independence applies only to the gradients of the inequality constraints that are active and the equality constraint gradients.

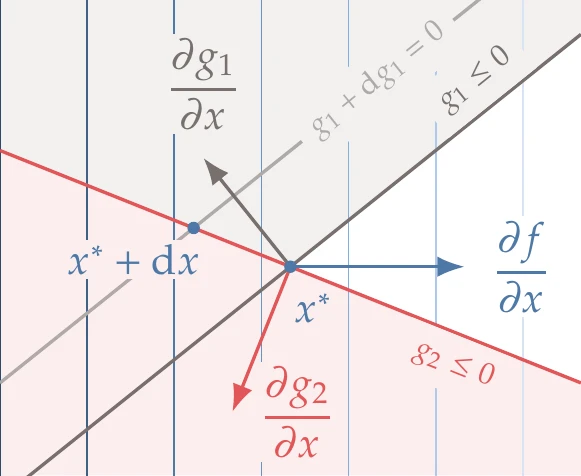

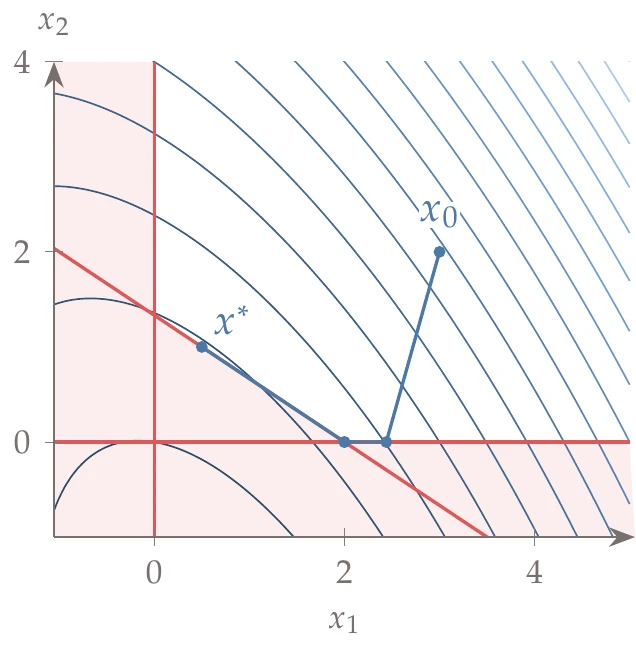

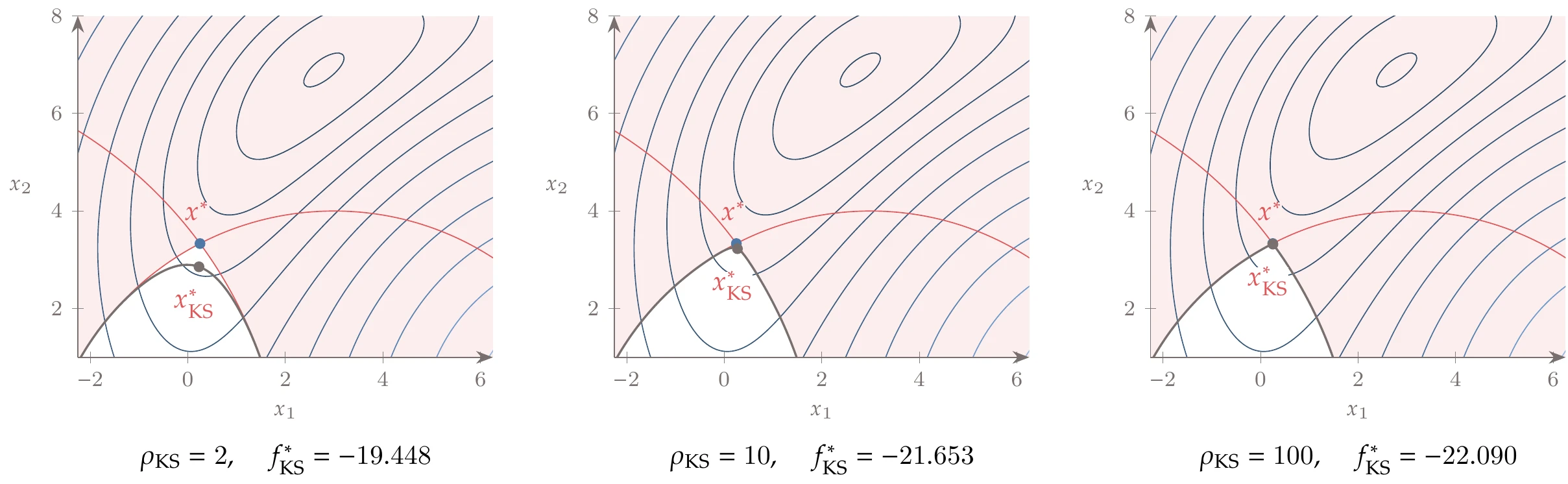

Suppose we have the two constraints shown in the left pane of Figure 5.19. For the given objective function contours, point is a minimum. At , the gradients of the two constraints are linearly independent, and is thus a regular point. Therefore, we can apply the KKT conditions at this point.

Figure 5.19:The KKT conditions apply only to regular points. A point is regular when the gradients of the constraints are linearly independent. The middle and right panes illustrate cases where is a constrained minimum but not a regular point.

The middle and right panes of Figure 5.19 illustrate cases where is also a constrained minimum. However, is not a regular point in either case because the gradients of the two constraints are not linearly independent. This means that the gradient of the objective cannot be expressed as a unique linear combination of the constraints. Therefore, we cannot use the KKT conditions, even though is a minimum. The problem would be ill-conditioned, and the numerical methods described in this chapter would run into numerical difficulties. Similar to the equality constrained case, this situation is uncommon in practice.

Although these examples can be solved analytically, they are the exception rather than the rule. The KKT conditions quickly become challenging to solve analytically (try solving Example 5.1), and as the number of constraints increases, trying all combinations of active and inactive constraints becomes intractable. Furthermore, engineering problems usually involve functions defined by models with implicit equations, which are impossible to solve analytically. The reason we include these analytic examples is to gain a better understanding of the KKT conditions. For the rest of the chapter, we focus on numerical methods, which are necessary for the vast majority of practical problems.

5.3.3 Meaning of the Lagrange Multipliers¶

The Lagrange multipliers quantify how much the corresponding constraints drive the design. More specifically, a Lagrange multiplier quantifies the sensitivity of the optimal objective function value to a variation in the value of the corresponding constraint. Here we explain why that is the case. We discuss only inequality constraints, but the same analysis applies to equality constraints.

When a constraint is inactive, the corresponding Lagrange multiplier is zero. This indicates that changing the value of an inactive constraint does not affect the optimum, as expected. This is only valid to the first order because the KKT conditions are based on the linearization of the objective and constraint functions. Because small changes are assumed in the linearization, we do not consider the case where an inactive constraint becomes active after perturbation.

Now let us examine the active constraints. Suppose that we want to quantify the effect of a change in an active (or equality) constraint on the optimal objective function value.[9]The differential of is given by the following dot product:

For all the other constraints that remain unperturbed, which means that

This equation states that any movement must be in the nullspace of the remaining constraints to remain feasible with respect to those constraints.[10]An example with two constraints is illustrated in Figure 5.24, where is perturbed and remains fixed. The objective and constraint functions are linearized because we are considering first-order changes represented by the differentials.

Figure 5.24:Lagrange multipliers can be interpreted as the change in the optimal objective due a perturbation in the corresponding constraint. In this case, we show the effect of perturbing .

From the KKT conditions (Equation 5.22), we know that at the optimum,

Using this condition, we can write the differential of the objective, , as

According to Equation 5.28 and Equation 5.29, the product with is only nonzero for the perturbed constraint and therefore,

This leads to the derivative of the optimal with respect to a change in the value of constraint :

Thus, the Lagrange multipliers can predict how much improvement can be expected if a given constraint is relaxed. For inequality constraints, because the Lagrange multipliers are positive at an optimum, this equation correctly predicts a decrease in the objective function value when the constraint value is increased.

The derivative defined in Equation 5.33 has practical value because it tells us how much a given constraint drives the design. In this interpretation of the Lagrange multipliers, we need to consider the scaling of the problem and the units. Still, for similar quantities, they quantify the relative importance of the constraints.

5.3.4 Post-Optimality Sensitivities¶

It is sometimes helpful to find sensitivities of the optimal objective function value with respect to a parameter held fixed during optimization. Suppose that we have found the optimum for a constrained problem. Say we have a scalar parameter held fixed in the optimization, but now want to quantify the effect of a perturbation in that parameter on the optimal objective value. Perturbing changes the objective and the constraint functions, so the optimum point moves, as illustrated in Figure 5.25. For our current purposes, we use to represent either active inequality or equality constraints.

We assume that the set of active constraints does not change with a perturbation in like we did when perturbing the constraint in Section 5.3.3.

Figure 5.25:Post-optimality sensitivities quantify the change in the optimal objective due to a perturbation of a parameter that was originally fixed in the optimization.

The optimal objective value changes due to changes in the optimum point (which moves to ) and objective function (which becomes .)

The objective function is affected by through a change in itself and a change induced by the movement of the constraints. This dependence can be written in the total differential form as:

The derivative corresponds to the derivative of the optimal value of the objective with respect to a perturbation in the constraint, which according to Equation 5.33, is the negative of the Lagrange multipliers. This means that the post-optimality derivative is

where the partial derivatives with respect to can be computed without re-optimizing.

5.4 Penalty Methods¶

The concept behind penalty methods is intuitive: to transform a constrained problem into an unconstrained one by adding a penalty to the objective function when constraints are violated or close to being violated. As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, penalty methods are no longer used directly in gradient-based optimization algorithms because they have difficulty converging to the true solution. However, these methods are still valuable because (1) they are simple and thus ease the transition into understanding constrained optimization; (2) they are useful in some constrained gradient-free methods (Chapter 7); (3) they can be used as merit functions in line search algorithms, as discussed in Section 5.5.3; (4) penalty concepts are used in interior points methods, as discussed in Section 5.6.

The penalized function can be written as

where is a penalty function, and the scalar is a penalty parameter. This is similar in form to the Lagrangian, but one difference is that is fixed instead of being a variable.

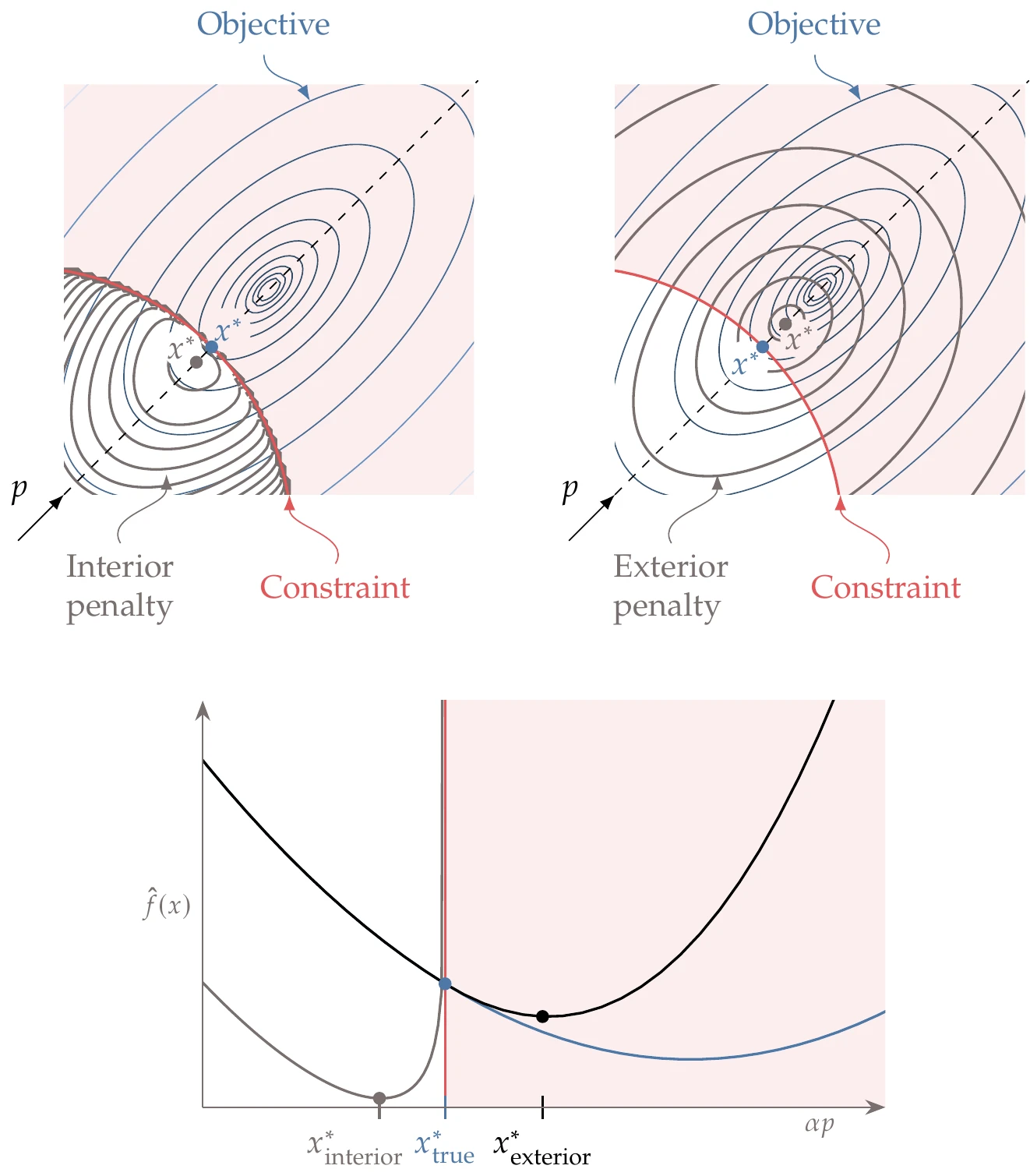

We can use the unconstrained optimization techniques to minimize . However, instead of just solving a single optimization problem, penalty methods usually solve a sequence of problems with different values of to get closer to the actual constrained minimum. We will see shortly why we need to solve a sequence of problems rather than just one problem.

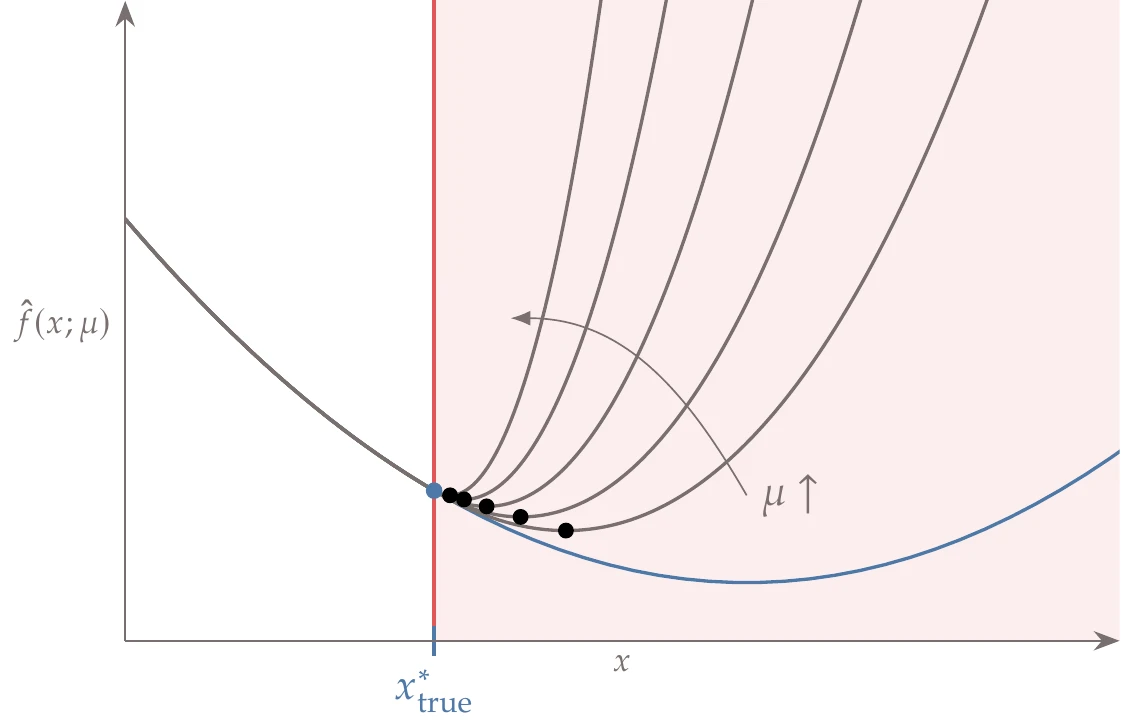

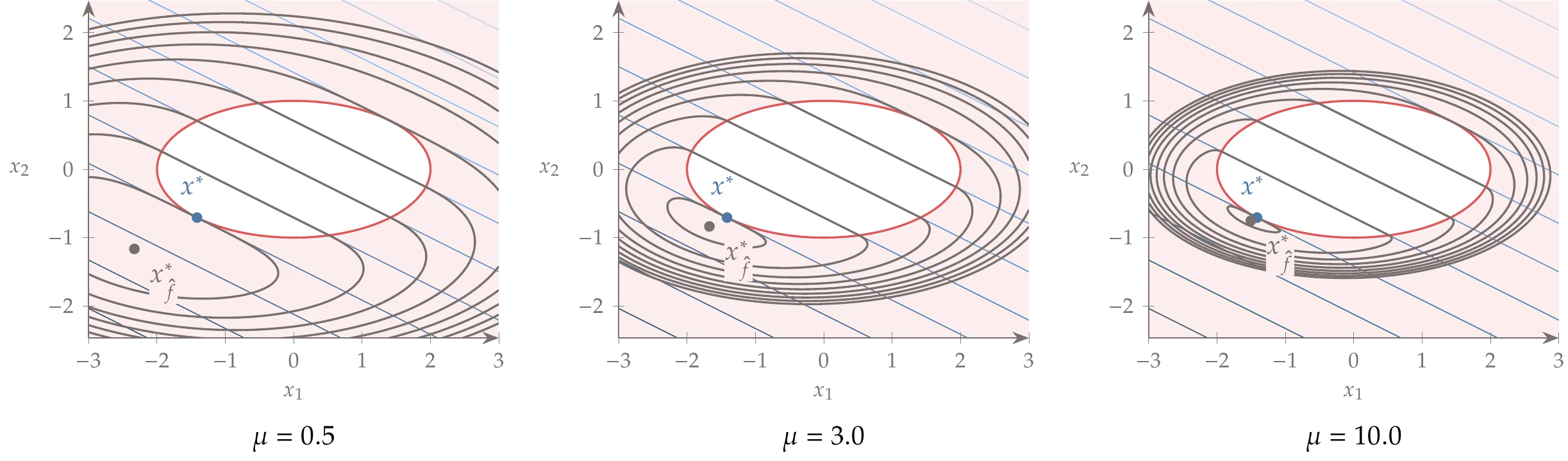

Various forms for can be used, leading to different penalty methods. There are two main types of penalty functions: exterior penalties, which impose a penalty only when constraints are violated, and interior penalty functions, which impose a penalty that increases as a constraint is approached.

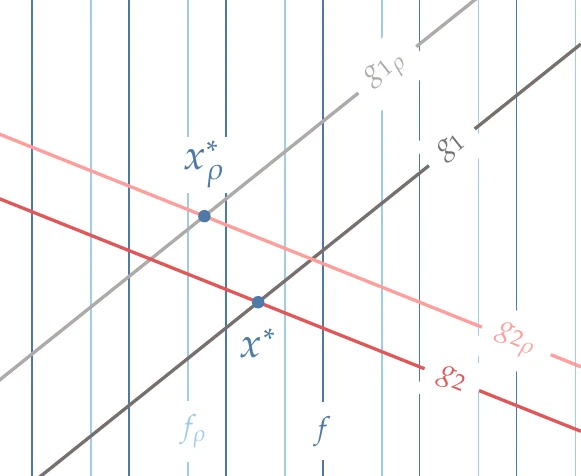

Figure 5.26 shows both interior and exterior penalties for a two-dimensional function. The exterior penalty leads to slightly infeasible solutions, whereas an interior penalty leads to a feasible solution but underpredicts the objective.

Figure 5.26:Interior penalties tend to infinity as the constraint is approached from the feasible side of the constraint (left), whereas exterior penalty functions activate when the points are not feasible (right). The minimum for both approaches is different from the true constrained minimum.

5.4.1 Exterior Penalty Methods¶

Of the many possible exterior penalty methods, we focus on two of the most popular ones: quadratic penalties and the augmented Lagrangian method. Quadratic penalties are continuously differentiable and straightforward to implement, but they suffer from numerical ill-conditioning. The augmented Lagrangian method is more sophisticated; it is based on the quadratic penalty but adds terms that improve the numerical properties. Many other penalties are possible, such as 1-norms, which are often used when continuous differentiability is unnecessary.

Quadratic Penalty Method¶

For equality constrained problems, the quadratic penalty method takes the form

where the semicolon denotes that is a fixed parameter. The motivation for a quadratic penalty is that it is simple and results in a function that is continuously differentiable. The factor of one half is unnecessary but is included by convention because it eliminates the extra factor of two when taking derivatives. The penalty is nonzero unless the constraints are satisfied (), as desired.

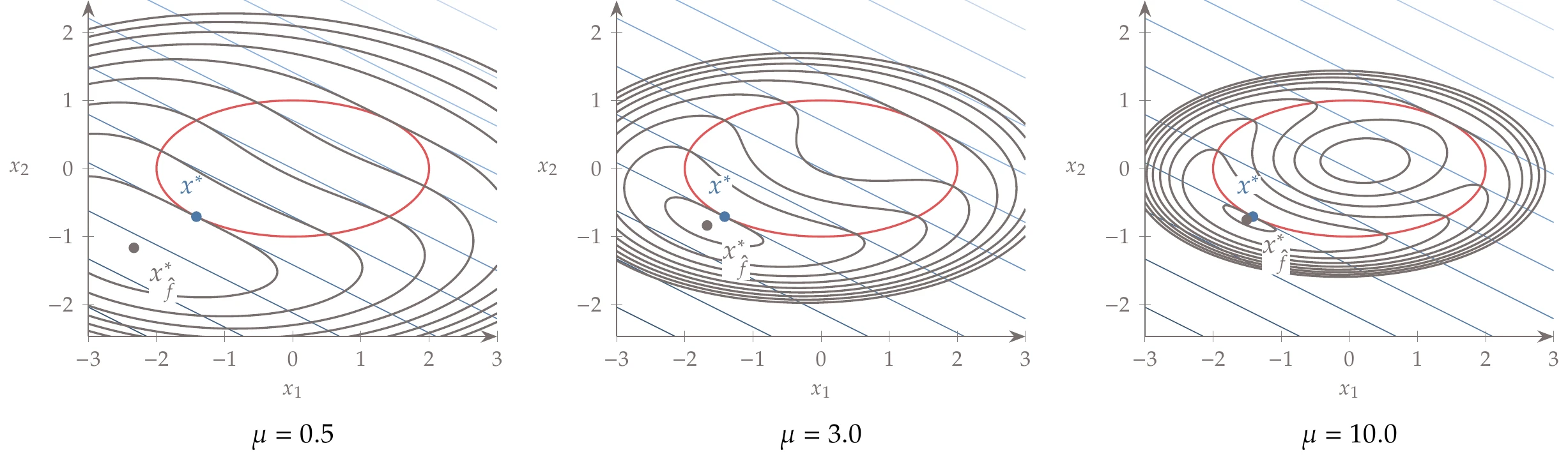

Figure 5.27:Quadratic penalty for an equality constrained problem. The minimum of the penalized function (black dots) approaches the true constrained minimum (blue circle) as the penalty parameter increases.

The value of the penalty parameter must be chosen carefully. Mathematically, we recover the exact solution to the constrained problem only as tends to infinity (see Figure 5.27). However, starting with a large value for is not practical. This is because the larger the value of , the larger the Hessian condition number, which corresponds to the curvature varying greatly with direction (see Example 4.10). This behavior makes the problem difficult to solve numerically.

To solve the problem more effectively, we begin with a small value of and solve the unconstrained problem. We then increase and solve the new unconstrained problem, using the previous solution as the starting point. We repeat this process until the optimality conditions (or some other approximate convergence criteria) are satisfied, as outlined in Algorithm 5.1. By gradually increasing and reusing the solution from the previous problem, we avoid some of the ill-conditioning issues. Thus, the original constrained problem is transformed into a sequence of unconstrained optimization problems.

There are three potential issues with the approach outlined in Algorithm 5.1. Suppose the starting value for is too low. In that case, the penalty might not be enough to overcome a function that is unbounded from below, and the penalized function has no minimum.

The second issue is that we cannot practically approach . Hence, the solution to the problem is always slightly infeasible. By comparing the optimality condition of the constrained problem,

and the optimality condition of the penalized function,

we see that for each constraint ,

Because at the optimum, must be large to satisfy the constraints.

The third issue has to do with the curvature of the penalized function, which is directly proportional to . The extra curvature is added in a direction perpendicular to the constraints, making the Hessian of the penalized function increasingly ill-conditioned as increases. Thus, the need to increase to improve accuracy directly leads to a function space that is increasingly challenging to solve.

Figure 5.28:The quadratic penalized function minimum approaches the constrained minimum as the penalty parameter increases.

Consider the equality constrained problem from Example 5.2. The penalized function for that case is

Figure 5.28 shows this function for different values of the penalty parameter . The penalty is active for all points that are infeasible, but the minimum of the penalized function does not coincide with the constrained minimum of the original problem. The penalty parameter needs to be increased for the minimum of the penalized function to approach the correct solution, but this results in a poorly conditioned function.

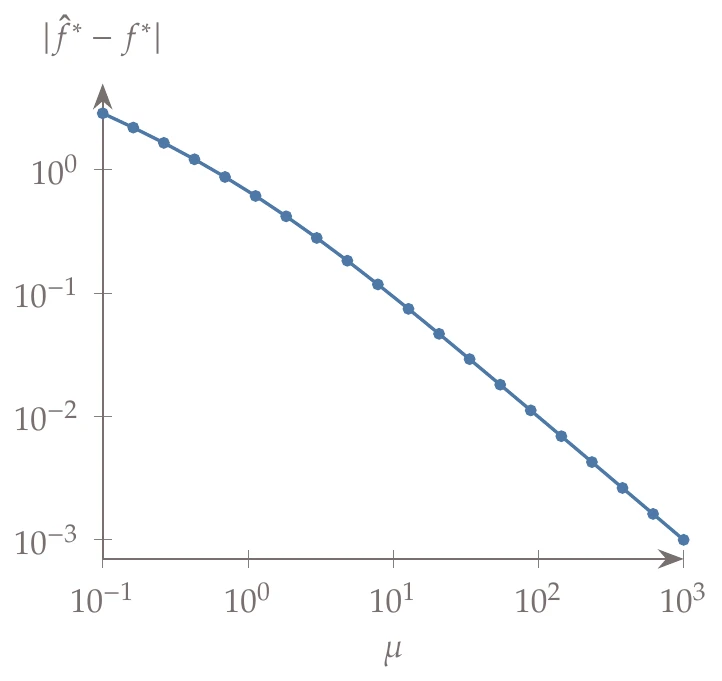

To show the impact of increasing , we solve a sequence of problems starting with a small value of and reusing the optimal point for one solution as the starting point for the next. Figure 5.29 shows that large penalty values are required for high accuracy. In this example, even using a penalty parameter of (which results in extremely skewed contours), the objective value achieves only three digits of accuracy.

Figure 5.29:Error in optimal solution for increasing penalty parameter.

The approach discussed so far handles only equality constraints, but we can extend it to handle inequality constraints. Instead of adding a penalty to both sides of the constraints, we add the penalty when the inequality constraint is violated (i.e., when ). This behavior can be achieved by defining a new penalty function as

The only difference relative to the equality constraint penalty shown in Figure 5.27 is that the penalty is removed on the feasible side of the inequality constraint, as shown in Figure 5.30.

Figure 5.30:Quadratic penalty for an inequality constrained problem. The minimum of the penalized function approaches the constrained minimum from the infeasible side.

The inequality quadratic penalty can be used together with the quadratic penalty for equality constraints if we need to handle both types of constraints:

The two penalty parameters can be incremented in lockstep or independently.

Consider the inequality constrained problem from Example 5.4. The penalized function for that case is

This function is shown in Figure 5.31 for different values of the penalty parameter . The contours of the feasible region inside the ellipse coincide with the original function contours. However, outside the feasible region, the contours change to create a function whose minimum approaches the true constrained minimum as the penalty parameter increases.

Figure 5.31:The quadratic penalized function minimum approaches the constrained minimum from the infeasible side.

The considerations on scaling discussed in Tip 4.4 are just as crucial for constrained problems. Similar to scaling the objective function, a good scaling rule of thumb is to normalize each constraint function such they are of order 1. For constraints, a natural scale is typically already defined by the limits we provide. For example, instead of

we can reexpress a scaled version as

Augmented Lagrangian¶

As explained previously, the quadratic penalty method requires a large value of for constraint satisfaction, but the large degrades the numerical conditioning. The augmented Lagrangian method helps alleviate this dilemma by adding the quadratic penalty to the Lagrangian instead of just adding it to the function. The augmented Lagrangian function for equality constraints is

To estimate the Lagrange multipliers, we can compare the optimality conditions for the augmented Lagrangian,

to those of the actual Lagrangian,

Comparing these two conditions suggests the approximation

Therefore, we update the vector of Lagrange multipliers based on the current estimate of the Lagrange multipliers and constraint values using

The complete algorithm is shown in Algorithm 5.2.

This approach is an improvement on the plain quadratic penalty because updating the Lagrange multiplier estimates at each iteration allows for more accurate solutions without increasing as much. The augmented Lagrangian approximation for each constraint obtained from Equation 5.49 is

The corresponding approximation in the quadratic penalty method is

The quadratic penalty relies solely on increasing in the denominator to drive the constraints to zero.

However, the augmented Lagrangian also controls the numerator through the Lagrange multiplier estimate. If the estimate is reasonably close to the true Lagrange multiplier, then the numerator becomes small for modest values of . Thus, the augmented Lagrangian can provide a good solution for while avoiding the ill-conditioning issues of the quadratic penalty.

Inputs:

: Starting point

: Initial Lagrange multiplier

: Initial penalty parameter

: Penalty increase factor

Outputs:

: Optimal point

: Corresponding function value

while not converged do

Update Lagrange multipliers

Increase penalty parameter

Update starting point for next optimization

end while

So far we have only discussed equality constraints where the definition for the augmented Lagrangian is universal. Example 5.8 included an inequality constraint by assuming it was active and treating it like an equality, but this is not an approach that can be used in general. Several formulations exist for handling inequality constraints using the augmented Lagrangian approach.456 One well-known approach is given by:7

where

Consider the inequality constrained problem from Example 5.4. Assuming the inequality constraint is active, the augmented Lagrangian (Equation 5.46) is

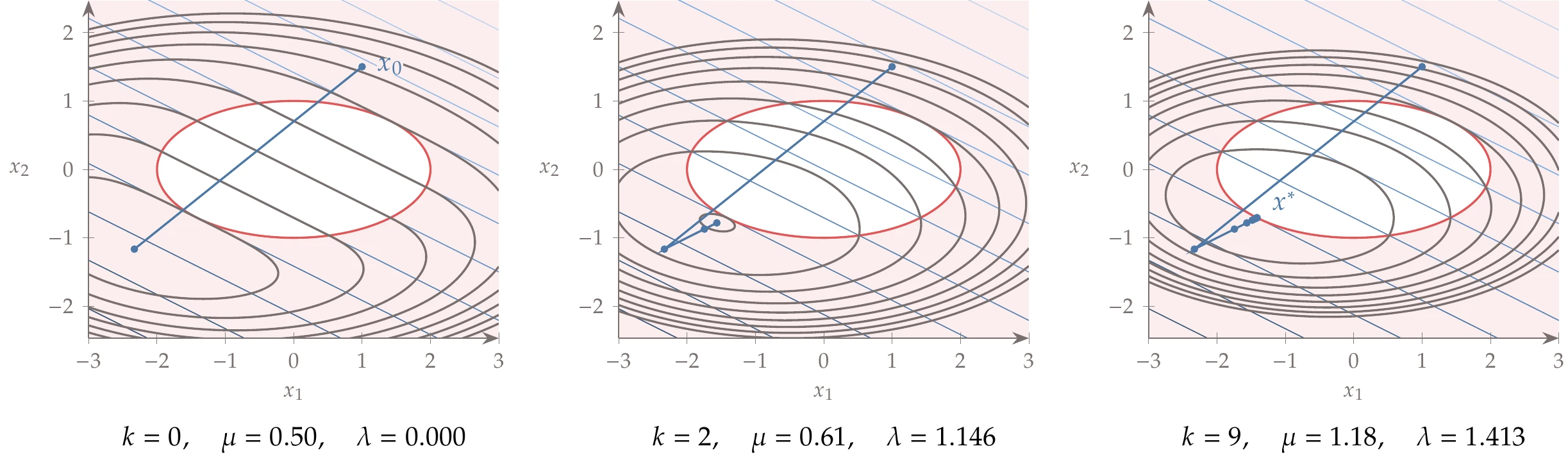

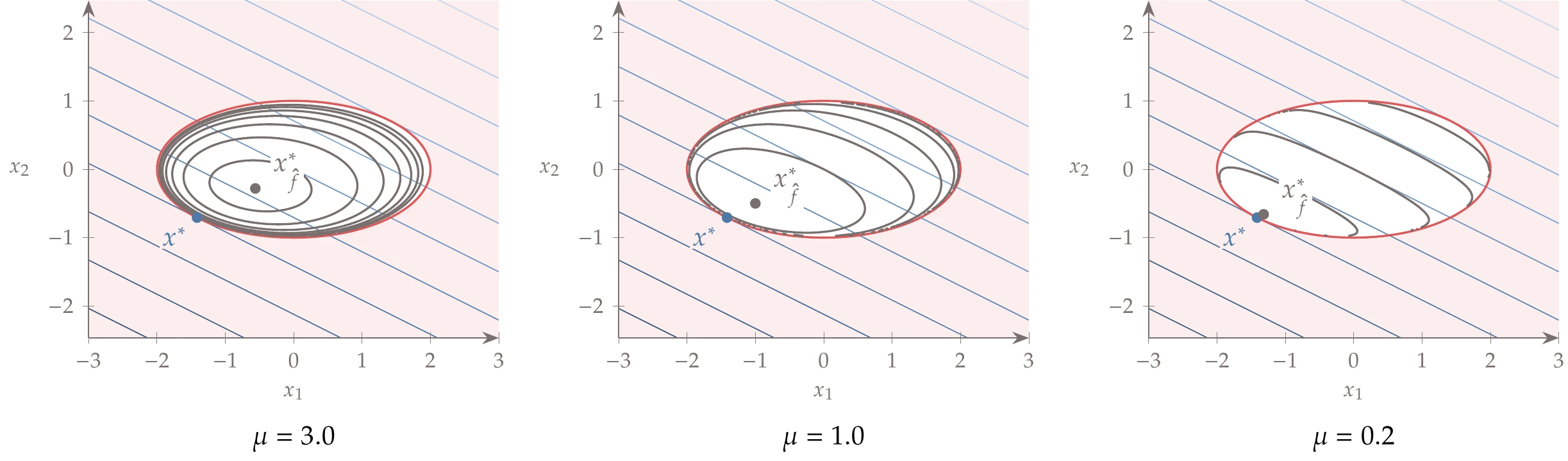

Applying Algorithm 5.2, starting with and using , we get the iterations shown in Figure 5.32.

Figure 5.32:Augmented Lagrangian applied to inequality constrained problem.

Compared with the quadratic penalty in Example 5.7, the penalized function is much better conditioned, thanks to the term associated with the Lagrange multiplier. The minimum of the penalized function eventually becomes the minimum of the constrained problem without a large penalty parameter.

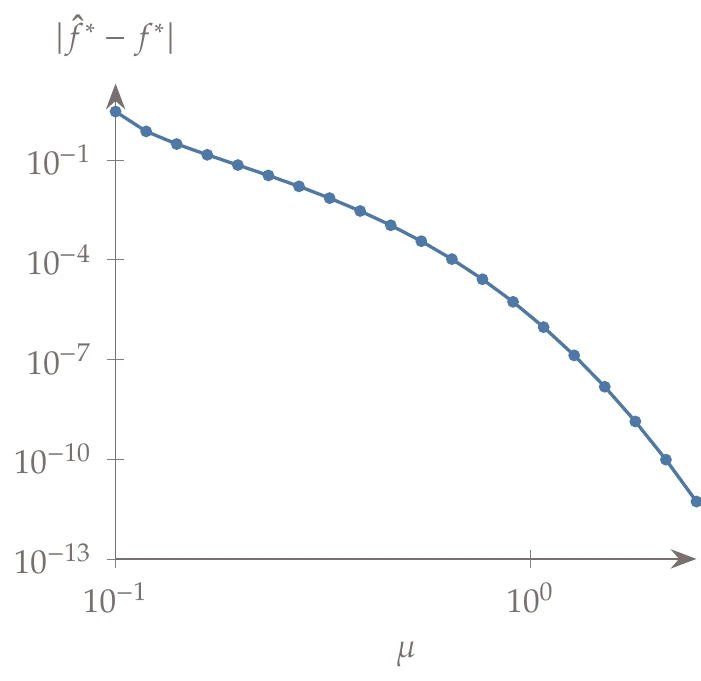

Figure 5.33:Error in optimal solution as compared with true solution as a function of an increasing penalty parameter.

As done in Example 5.6, we solve a sequence of problems starting with a small value of and reusing the optimal point for one solution as the starting point for the next. In this case, we update the Lagrange multiplier estimate between optimizations as well. Figure 5.33 shows that only modest penalty parameters are needed to achieve tight convergence to the true solution, a significant improvement over the regular quadratic penalty.

5.4.2 Interior Penalty Methods¶

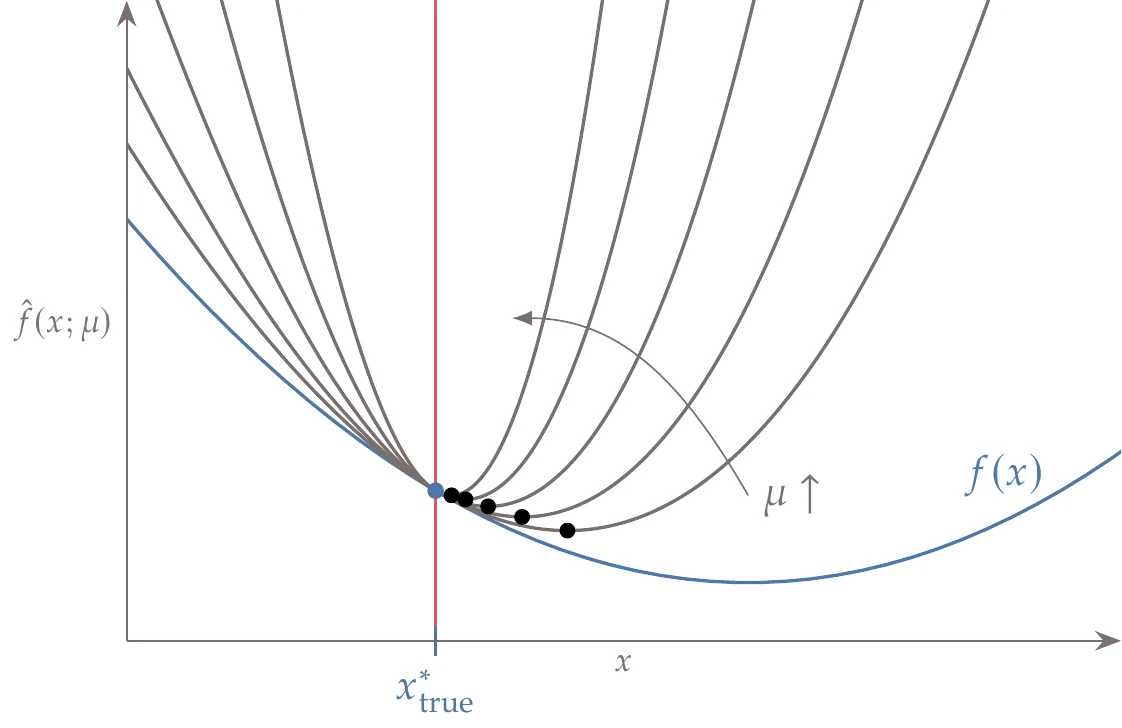

Interior penalty methods work the same way as exterior penalty methods—they transform the constrained problem into a series of unconstrained problems. The main difference with interior penalty methods is that they always seek to maintain feasibility. Instead of adding a penalty only when constraints are violated, they add a penalty as the constraint is approached from the feasible region. This type of penalty is particularly desirable if the objective function is ill-defined outside the feasible region. These methods are called interior because the iteration points remain on the interior of the feasible region. They are also referred to as barrier methods because the penalty function acts as a barrier preventing iterates from leaving the feasible region.

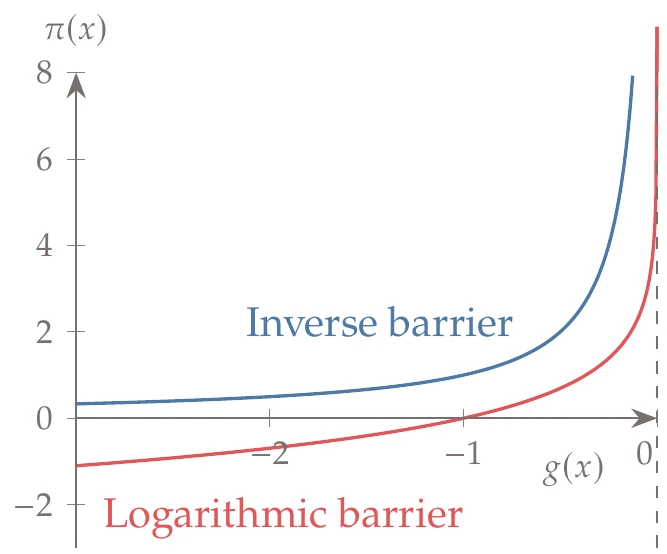

Figure 5.34:Two different interior penalty functions: inverse barrier and logarithmic barrier.

One possible interior penalty function to enforce is the inverse barrier,

where as (where the superscript “” indicates a left-sided derivative). A more popular interior penalty function is the logarithmic barrier,

which also approaches infinity as the constraint tends to zero from the feasible side. The penalty function is then

These two penalty functions as illustrated in Figure 5.34.

Neither of these penalty functions applies when because they are designed to be evaluated only within the feasible space. Algorithms based on these penalties must be prevented from evaluating infeasible points.

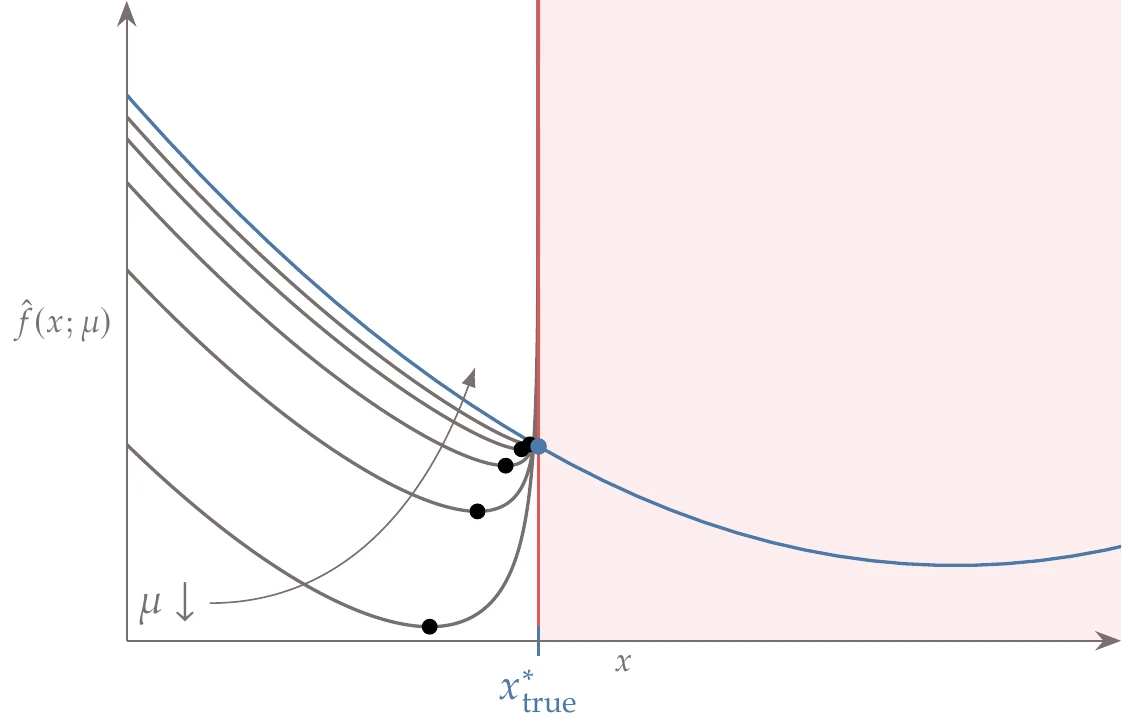

Like exterior penalty methods, interior penalty methods must also solve a sequence of unconstrained problems but with (see Algorithm 5.3). As the penalty parameter decreases, the region across which the penalty acts decreases, as shown in Figure 5.35.

Figure 5.35:Logarithmic barrier penalty for an inequality constrained problem. The minimum of the penalized function (black circles) approaches the true constrained minimum (blue circle) as the penalty parameter decreases.

The methodology is the same as is described in Algorithm 5.1 but with a decreasing penalty parameter. One major weakness of the method is that the penalty function is not defined for infeasible points, so a feasible starting point must be provided. For some problems, providing a feasible starting point may be difficult or practically impossible.

The optimization must be safeguarded to prevent the algorithm from becoming infeasible when starting from a feasible point. This can be achieved by checking the constraints values during the line search and backtracking if any of them is greater than or equal to zero. Multiple backtracking iterations might be required.

Inputs:

: Starting point

: Initial penalty parameter

: Penalty decrease factor

Outputs:

: Optimal point

: Corresponding function value

while not converged do

Decrease penalty parameter

Update starting point for next optimization

end while

Consider the equality constrained problem from Example 5.4. The penalized function for that case using the logarithmic penalty (Equation 5.57) is

Figure 5.36 shows this function for different values of the penalty parameter . The penalized function is defined only in the feasible space, so we do not plot its contours outside the ellipse.

Figure 5.36:Logarithmic penalty for one inequality constraint. The minimum of the penalized function approaches the constrained minimum from the feasible side.

Like exterior penalty methods, the Hessian for interior penalty methods becomes increasingly ill-conditioned as the penalty parameter tends to zero.8 There are augmented and modified barrier approaches that can avoid the ill-conditioning issue (and other methods that remain ill-conditioned but can still be solved reliably, albeit inefficiently).9 However, these methods have been superseded by the modern interior-point methods discussed in Section 5.6, so we do not elaborate on further improvements to classical penalty methods.

5.5 Sequential Quadratic Programming¶

SQP is the first of the modern constrained optimization methods we discuss. SQP is not a single algorithm; instead, it is a conceptual method from which various specific algorithms are derived. We present the basic method but mention only a few of the many details needed for robust practical implementations. We begin with equality constrained SQP and then add inequality constraints.

5.5.1 Equality Constrained SQP¶

To derive the SQP method, we start with the KKT conditions for this problem and treat them as equation residuals that need to be solved. Recall that the Lagrangian (Equation 5.12) is

Differentiating this function with respect to the design variables and Lagrange multipliers and setting the derivatives to zero, we get the KKT conditions,

Recall that to solve a system of equations using Newton’s method, we solve a sequence of linear systems,

where is the Jacobian of derivatives . The step in the variables is , where the variables are

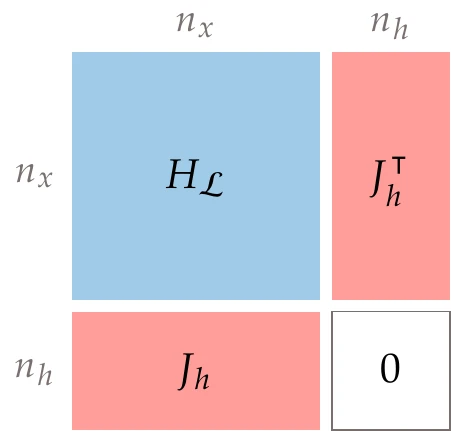

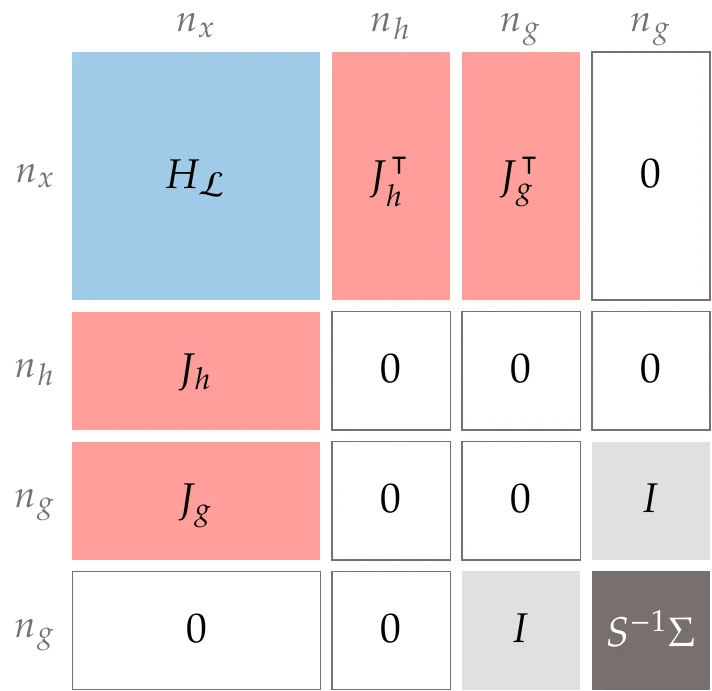

Differentiating the vector of residuals (Equation 5.59) with respect to the two concatenated vectors in yields the following block linear system:

This is a linear system of equations where the Jacobian matrix is square.

Figure 5.37:Structure and block shapes for the matrix in the SQP system (Equation 5.62)

The shape of the matrix and its blocks are as shown in Figure 5.37. We solve a sequence of these problems to converge to the optimal design variables and the corresponding optimal Lagrange multipliers. At each iteration, we update the design variables and Lagrange multipliers as follows:

The inclusion of suggests that we do not automatically accept the Newton step (which corresponds to ) but instead perform a line search as previously described in Section 4.3. The function used in the line search needs some modification, as discussed later in this section.

SQP can be derived in an alternative way that leads to different insights. This alternate approach requires an understanding of quadratic programming (QP), which is discussed in more detail in Section 11.3 but briefly described here. A QP problem is an optimization problem with a quadratic objective and linear constraints. In a general form, we can express any equality constrained QP as

A two-dimensional example with one constraint is illustrated in Figure 5.38.

Figure 5.38:Quadratic problem in two dimensions.

The constraint is a matrix equation that represents multiple linear equality constraints—one for every row in . We can solve this optimization problem analytically from the optimality conditions. First, we form the Lagrangian:

We now take the partial derivatives and set them equal to zero:

We can express those same equations in a block matrix form:

This is like the procedure we used in solving the KKT conditions, except that these are linear equations, so we can solve them directly without any iteration. As in the unconstrained case, finding the minimum of a quadratic objective results in a system of linear equations.

As long as is positive definite, then the linear system always has a solution, and it is the global minimum of the QP.[11]The ease with which a QP can be solved provides a strong motivation for SQP. For a general constrained problem, we can make a local QP approximation of the nonlinear model, solve the QP, and repeat this process until convergence. This method involves iteratively solving a sequence of quadratic programming problems, hence the name sequential quadratic programming.

To form the QP, we use a local quadratic approximation of the Lagrangian (removing the constant term because it does not change the solution) and a linear approximation of the constraints for some step near our current point. In other words, we locally approximate the problem as the following QP:

We substitute the gradient of the Lagrangian into the objective:

Then, we substitute the constraint into the objective:

Now, we can remove the last term in the objective because it does not depend on the variable (), resulting in the following equivalent problem:

Using the QP solution method outlined previously results in the following system of linear equations:

Replacing and multiply through:

Subtracting the second term on both sides yields

which is the same linear system we found from applying Newton’s method to the KKT conditions (Equation 5.62).

This derivation relies on the somewhat arbitrary choices of choosing a QP as the subproblem and using an approximation of the Lagrangian with constraints (rather than an approximation of the objective with constraints or an approximation of the Lagrangian with no constraints).[12] Nevertheless, it is helpful to conceptualize the method as solving a sequence of QPs. This concept will motivate the solution process once we add inequality constraints.

5.3.2 Inequality Constraints¶

Introducing inequality constraints adds complications. For inequality constraints, we cannot solve the KKT conditions directly as we could for equality constraints. This is because the KKT conditions include the complementary slackness conditions , which we cannot solve directly. Even though the number of equations in the KKT conditions is equal to the number of unknowns, the complementary conditions do not provide complete information (they just state that each constraint is either active or inactive). Suppose we knew which of the inequality constraints were active () and which were inactive () at the optimum. Then, we could use the same approach outlined in the previous section, treating the active constraints as equality constraints and ignoring the inactive constraints. Unfortunately, we do not know which constraints are active at the optimum beforehand in general. Finding which constraints are active in an iterative way is challenging because we would have to try all possible combinations of active constraints. This is intractable if there are many constraints.

A common approach to handling inequality constraints is to use an active-set method. The active set is the set of constraints that are active at the optimum (the only ones we ultimately need to enforce). Although the actual active set is unknown until the solution is found, we can estimate this set at each iteration. This subset of potentially active constraints is called the working set.

The working set is then updated at each iteration.

Similar to the SQP developed in the previous section for equality constraints, we can create an algorithm based on solving a sequence of QPs that linearize the constraints.[13] We extend the equality constrained QP (Equation 5.69) to include the inequality constraints as follows:

The determination of the working set could happen in the inner loop, that is, as part of the inequality constrained QP subproblem (Equation 5.76). Alternatively, we could choose a working set in the outer loop and then solve the QP subproblem with only equality constraints (Equation 5.69), where the working-set constraints would be posed as equalities. The former approach is more common and is discussed here. In that case, we need consider only the active-set problem in the context of a QP. Many variations on active-set methods exist; we outline just one such approach based on a binding-direction method.

The general QP problem we need to solve is as follows:

We assume that is positive definite so that this problem is convex. Here, corresponds to the Lagrangian Hessian. Using an appropriate quasi-Newton approximation (which we will discuss in Section 5.5.4) ensures a positive definite Lagrangian Hessian approximation.

Consider iteration in an SQP algorithm that handles inequality constraints. At the end of the previous iteration, we have a design point and a working set . The working set in this approach is a set of row indices corresponding to the subset of inequality constraints that are active at .[14]Then, we consider the corresponding inequality constraints to be equalities, and we write:

where and correspond to the rows of the inequality constraints specified in the working set.

The constraints in the working set, combined with the equality constraints, must be linearly independent. Thus, we cannot include more working-set constraints (plus equality constraints) than design variables.

Although the active set is unique, there can be multiple valid choices for the working set.

Assume, for the moment, that the working set does not change at nearby points (i.e., we ignore the constraints outside the working set). We seek a step to update the design variables as follows: . We find by solving the following simplified QP that considers only the working set:

We solve this QP by varying , so after multiplying out the terms in the objective, we can ignore the terms that do not depend on . We can also simplify the constraints because we know the constraints were satisfied at the previous iteration (i.e., and ). The simplified problem is as follows:

We now have an equality constrained QP that we can solve using the methods from the previous section.

Figure 5.39:Structure of the QP subproblem within the inequality constrained QP solution process.

Using Equation 5.68, the KKT solution to this problem is as follows:

Figure 5.39 shows the structure of the matrix in this linear system.

Let us consider the case where the solution of this linear system is nonzero. Solving the KKT conditions in Equation 5.80 ensures that all the constraints in the working set are still satisfied at . Still, there is no guarantee that the step does not violate some of the constraints outside of our working set. Suppose that and define the constraints outside of the working set. If

for all rows, all the constraints are still satisfied. In that case, we accept the step and update the design variables as follows:

The working set remains unchanged as we proceed to the next iteration.

Otherwise, if some of the constraints are violated, we cannot take the full step and reduce it the step length by as follows:

We cannot take the full step (), but we would like to take as large a step as possible while still keeping all the constraints feasible.

Let us consider how to determine the appropriate step size, . Substituting the step update (Equation 5.84) into the equality constraints, we obtain the following:

We know that from solving the problem at the previous iteration. Also, we just solved under the condition that . Therefore, the equality constraints (Equation 5.85) remain satisfied for any choice of . By the same logic, the constraints in our working set remain satisfied for any choice of as well.

Now let us consider the constraints that are not in the working set.

We denote as row of the matrix (associated with the inequality constraints outside of the working set). If these constraints are to remain satisfied, we require

After rearranging, this condition becomes

We do not divide through by yet because the direction of the inequality would change depending on its sign. We consider the two possibilities separately. Because the QP constraints were satisfied at the previous iteration, we know that for all . Thus, the right-hand side is always positive. If is negative, then the inequality will be satisfied for any choice of . Alternatively, if is positive, we can rearrange Equation 5.87 to obtain the following:

This equation determines how large can be without causing one of the constraints outside of the working set to become active. Because multiple constraints may become active, we have to evaluate for each one and choose the smallest among all constraints.

A constraint for which is said to be blocking. In other words, if we had included that constraint in our working set before solving the QP, it would have changed the solution. We add one of the blocking constraints to the working set, and proceed to the next iteration.[15]Now consider the case where the solution to Equation 5.81 is . If all inequality constraint Lagrange multipliers are positive (), the KKT conditions are satisfied and we have solved the original inequality constrained QP. If one or more values are negative, additional iterations are needed. We find the value that is most negative, remove constraint from the working set, and proceed to the next iteration.

As noted previously, all the constraints in the reduced QP (the equality constraints plus all working-set constraints) must be linearly independent and thus has full row rank. Otherwise, there would be no solution to Equation 5.81. Therefore, the starting working set might not include all active constraints at and must instead contain only a subset, such that linear independence is maintained.

Similarly, when adding a blocking constraint to the working set, we must again check for linear independence. At a minimum, we need to ensure that the length of the working set does not exceed . The complete algorithm for solving an inequality constrained QP is shown in Algorithm 5.4.

Equality constraints are less common in engineering design problems than inequality constraints. Sometimes we pose a problem as an equality constraint unnecessarily. For example, the simulation of an aircraft in steady-level flight may require the lift to equal the weight. Formally, this is an equality constraint, but it can also be posed as an inequality constraint (lift greater or equal to weight). There is no advantage to having more lift than the required because it increases drag, so the constraint is always active at the optimum. When such a constraint is not active at the solution, it can be a helpful indicator that something is wrong with the formulation, the optimizer, or the assumptions. Although an equality constraint is more natural from the algorithm perspective, the flexibility of the inequality constraint might allow the optimizer to explore the design space more effectively.

Consider another example: a propeller design problem might require a specified thrust. Although an equality constraint would likely work, it is more constraining than necessary. If the optimal design were somehow able to produce excess thrust, we would accept that design. Thus, we should not formulate the constraint in an unnecessarily restrictive way.

Inputs:

: Matrices and vectors defining the QP (Equation 5.77); Q must be positive definite

: Tolerance used for termination and for determining whether constraint is active

Outputs:

: Optimal point

One possible

initial working set

while true do

set and for all Select rows for working set

Solve the KKT system (Equation 5.81)

if then

if then

Satisfied KKT conditionsreturn

else

Remove from working set

end if

else

Initialize with optimum step

Blocking index

for do

Checkconstraints outside of working setif then

Potential blocking constraintis a row of

if then

Save or overwrite blocking index

end if

end if

end for

Add to working set (if linearly independent)

end if

end while

Let us solve the following problem using the active-set QP algorithm:

Rewriting in the standard form (Equation 5.77) yields the following:

Figure 5.40:Iteration history for the active-set QP example.

We arbitrarily chose as a starting point. Because none of the constraints are active, the initial working set is empty, . At each iteration, we solve the QP formed by the equality constraints and any constraints in the active set (treated as equality constraints). The sequence of iterations is detailed as follows and is plotted in Figure 5.40:

The QP subproblem yields and . Next, we check whether any constraints are blocking at the new point . Because all three constraints are outside of the working set, we check all three. Constraint 1 is potentially blocking () and leads to . Constraint 2 is also potentially blocking and leads to . Finally, constraint 3 is also potentially blocking and leads to . We choose the constraint with the smallest , which is constraint 3, and add it to our working set. At the end of the iteration, and .

The new QP subproblem yields and . Constraints 1 and 2 are outside the working set. Constraint 1 is potentially blocking and gives ; constraint 2 is also potentially blocking and yields . Because constraint 1 yields the smaller step, we add it to the working set. At the end of the iteration, and .

The QP subproblem now yields and . Because , we check for convergence. One of the Lagrange multipliers is negative, so this cannot be a solution. We remove the constraint associated with the most negative Lagrange multiplier from the working set (constraint 3). At the end of the iteration, is unchanged at , and .

The QP yields and . Constraint 2 is potentially blocking and yields (which means it is not blocking because ). Constraint 3 is also not blocking (). None of the values was blocking, so we can take the full step (). The new point is , and the working set is unchanged at .

The QP yields . Because , we check for convergence. All Lagrange multipliers are nonnegative, so the problem is solved. The solution to the original inequality constrained QP is then .

Because SQP solves a sequence of QPs, an effective approach is to use the optimal and active set from the previous QP as the starting point and working set for the next QP. The algorithm outlined in this section requires both a feasible starting point and a working set of linearly independent constraints. Although the previous starting point and working set usually satisfy these conditions, this is not guaranteed, and adjustments may be necessary.

Algorithms to determine a feasible point are widely used (often by solving a linear programming problem). There are also algorithms to remove or add to the constraint matrix as needed to ensure full rank.12

There are often multiple mathematically equivalent ways to pose the problem constraints. Reformulating can sometimes yield equivalent problems that are significantly easier to solve.

In some cases, it can help to add redundant constraints to avoid areas of the design space that are not useful. Similarly, we should consider whether the model that computes the objective and constraint functions should be solved separately or posed as constraints at the optimizer level (as we did in Equation 3.33).

5.5.3 Merit Functions and Filters¶

Similar to what we did in unconstrained optimization, we do not directly accept the step returned from solving the subproblem (Equation 5.62 or Equation 5.76). Instead, we use as the first step length in a line search.

In the line search for unconstrained problems (Section 4.3), determining if a point was good enough to terminate the search was based solely on comparing the objective function value (and the slope when enforcing the strong Wolfe conditions). For constrained optimization, we need to make some modifications to these methods and criteria.

In constrained optimization, objective function decrease and feasibility often compete with each other. During a line search, a new point may decrease the objective but increase the infeasibility, or it may decrease the infeasibility but increase the objective. We need to take these two metrics into account to determine the line search termination criterion.

The Lagrangian is a function that accounts for the two metrics. However, at a given iteration, we only have an estimate of the Lagrange multipliers, which can be inaccurate.

One way to combine the objective value with the constraints in a line search is to use merit functions, which are similar to the penalty functions introduced in Section 5.4. Common merit functions include functions that use the norm of constraint violations:

where is 1 or 2 and are the constraint violations, defined as

The augmented Lagrangian from Section 5.4.1 can also be repurposed for a constrained line search (see Equation 5.53 and Equation 5.54).

Like penalty functions, one downside of merit functions is that it is challenging to choose a suitable value for the penalty parameter . This parameter needs to be large to ensure feasibility. However, if it is too large, a full Newton step might not be permitted. This might slow the convergence unnecessarily. Using the augmented Lagrangian can help, as discussed in Section 5.4.1. However, there are specific techniques used in SQP line searches and various safeguarding techniques needed for robustness.

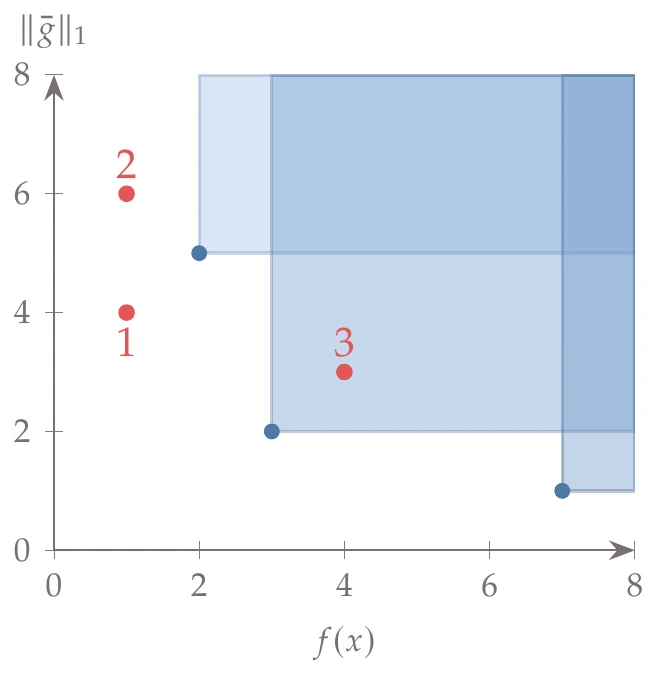

Filter methods are an alternative to using penalty-based methods in a line search.13 Filter methods interfere less with the full Newton step and are effective for both SQP and interior-point methods (which are introduced in Section 5.6).1415 The approach is based on concepts from multiobjective optimization, which is the subject of Chapter 9. In the filter method, there are two objectives: decrease the objective function and decrease infeasibility. A point is said to dominate another if its objective is lower and the sum of its constraint violations is lower. The filter consists of all the points that have been found to be non-dominated in the line searches so far. The line search terminates when it finds a point that is not dominated by any point in the current filter. That new point is then added to the filter, and any points that it dominates are removed from the filter.[16]This is only the basic concept. Robust implementation of a filter method requires imposing sufficient decrease conditions, not unlike those in the unconstrained case, and several other modifications. Fletcher et al. (2006) provide more details on filter methods.

A filter consists of pairs , where is the sum of the constraint violations (Equation 5.90). Suppose that the current filter contains the following three points: . None of the points in the filter dominates any other. These points are plotted as the blue dots in Figure 5.41, where the shaded regions correspond to all the points that are dominated by the points in the filter.

Figure 5.41:Filter method example showing three points in the filter (blue dots); the shaded regions correspond to all the points that are dominated by the filter. The red dots illustrate three different possible outcomes when new points are considered.

During a line search, a new candidate point is evaluated. There are three possible outcomes. Consider the following three points that illustrate these three outcomes (corresponding to the labeled points in Figure 5.41):

: This point is not dominated by any point in the filter. The step is accepted, the line search ends, and this point is added to the filter. Because this new point dominates one of the points in the filter, , that dominated point is removed from the filter. The current set in the filter is now .

: This point is not dominated by any point in the filter. The step is accepted, the line search ends, and this new point is added to the filter. Unlike the previous case, none of the points in the filter are dominated. Therefore, no points are removed from the filter set, which becomes .

: This point is dominated by a point in the filter, . The step is rejected, and the line search continues by selecting a new candidate point. The filter is unchanged.

5.5.4 Quasi-Newton SQP¶

In the discussion of the SQP method so far, we have assumed that we have the Hessian of the Lagrangian . Similar to the unconstrained optimization case, the Hessian might not be available or be too expensive to compute. Therefore, it is desirable to use a quasi-Newton approach that approximates the Hessian, as we did in Section 4.4.4.

The difference now is that we need an approximation of the Lagrangian Hessian instead of the objective function Hessian. We denote this approximation at iteration as .

Similar to the unconstrained case, we can approximate using the gradients of the Lagrangian and a quasi-Newton update, such as the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) update.

Unlike in unconstrained optimization, we do not want the inverse of the Hessian directly. Therefore, we use the version of the BFGS formula that computes the Hessian (Equation 4.87):

where:

The step in the design variable space, , is the step that resulted from the latest line search. The Lagrange multiplier is fixed to the latest value when approximating the curvature of the Lagrangian because we only need the curvature in the space of the design variables.

Recall that for the QP problem (Equation 5.76) to have a solution, must be positive definite. To ensure a positive definite approximation, we can use a damped BFGS update.16[17]

This method replaces with a new vector , defined as

where the scalar is defined as

which can range from 0 to 1. We then use the same BFGS update formula (Equation 5.91), except that we replace each with .

To better understand this update, let us consider the two extremes for . If , then Equation 5.93 in combination with Equation 5.91 yields ; that is, the Hessian approximation is unmodified. At the other extreme, yields the full BFGS update formula ( is set to ). Thus, the parameter provides a linear weighting between keeping the current Hessian approximation and using the full BFGS update.

The definition of (Equation 5.94) ensures that stays close enough to and remains positive definite. The damping is activated when the predicted curvature in the new latest step is below one-fifth of the curvature predicted by the latest approximate Hessian. This could happen when the function is flattening or when the curvature becomes negative.

5.5.5 Algorithm Overview¶

We now put together the various pieces in a high-level description of SQP with quasi-Newton approximations in Algorithm 5.5.[18] For the convergence criterion, we can use an infinity norm of the KKT system residual vector. For better control over the convergence, we can consider two separate tolerances: one for the norm of the optimality and another for the norm of the feasibility. For problems that only have equality constraints, we can solve the corresponding QP (Equation 5.62) instead.

Inputs:

: Starting point

: Optimality tolerance

: Feasibility tolerance

Outputs:

: Optimal point

: Corresponding function value

Initial Lagrange multipliers

For line search

Evaluate functions () and derivatives ()

while or do

if or reset = true then

Initialize to identity matrix or scaled version (Equation 4.95)

else

Update Compute damped BFGS (Equation 5.91, Equation 5.92, Equation 5.93, and Equation 5.94)

end if

Solve QP subproblem (Equation 5.76) for

Use merit function or filter (Section 5.5.3)

Update step

Active set becomes initial working set for next QP

Evaluate functions () and derivatives ()

end while

We now solve Example 5.2 using the SQP method (Algorithm 5.5). We start at with an initial Lagrange multiplier and an initial estimate of the Lagrangian Hessian as for simplicity. The line search uses an augmented Lagrangian merit function with a fixed penalty parameter () and a quadratic bracketed search as described in Section 4.3.2. The choice between a merit function and line search has only a small effect in this simple problem. The gradient of the equality constraint is

and differentiating the Lagrangian with respect to yields

The KKT system to be solved (Equation 5.62) in the first iteration is

The solution of this system is . Using , the full step satisfies the strong Wolfe conditions, so for the new iteration we have , .

To update the approximate Hessian using the damped BFGS update (Equation 5.93), we need to compare the values of and . Because , we need to compute the scalar using Equation 5.94. This results in a partial BFGS update to maintain positive definiteness. After a few iterations, for the remainder of the optimization, corresponding to a full BFGS update. The initial estimate for the Lagrangian Hessian is poor (just a scaled identity matrix), so some damping is necessary. However, the estimate is greatly improved after a few iterations. Using the quasi-Newton update in Equation 5.91, we get the approximate Hessian for the next iteration as

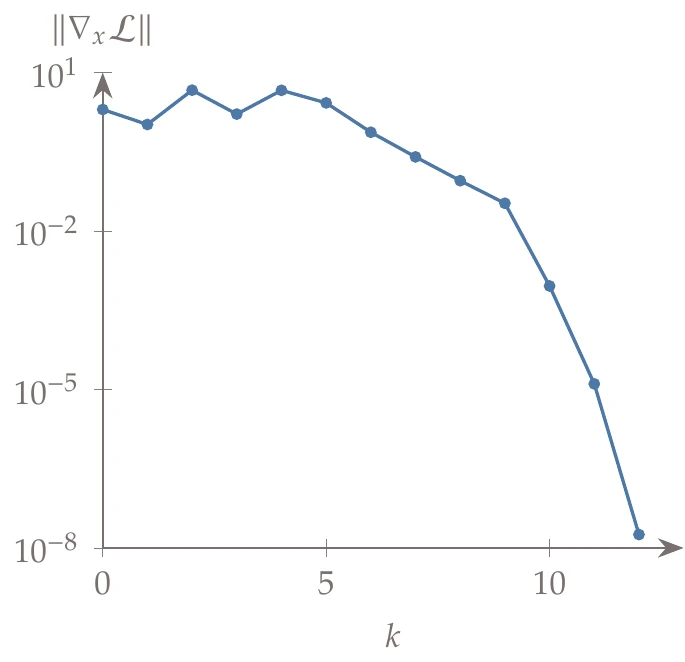

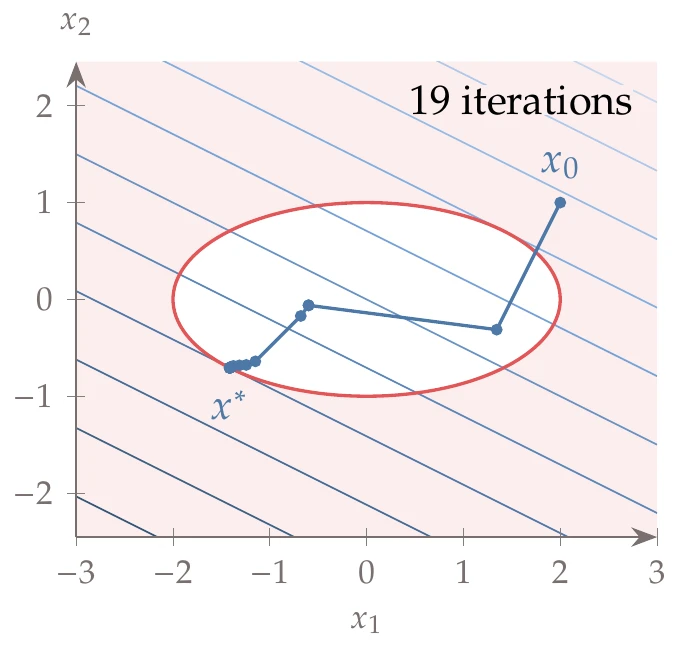

Figure 5.42:SQP algorithm iterations.

We repeat this process for subsequent iterations, as shown in Figure 5.42. The gray contours show the QP subproblem (Equation 5.72) solved at each iteration: the quadratic objective appears as elliptical contours and the linearized constraint as a straight line. The starting point is infeasible, and the iterations remain infeasible until the last few iterations.

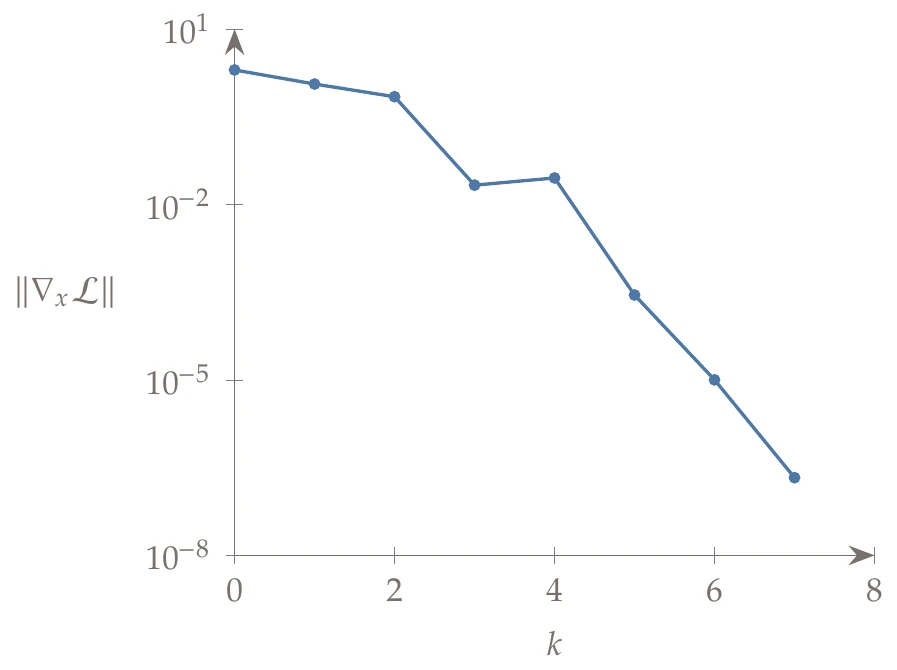

Figure 5.43:Convergence history of the norm of the Lagrangian gradient.

This behavior is common for SQP because although it satisfies the linear approximation of the constraints at each step, it does not necessarily satisfy the constraints of the actual problem, which is nonlinear. As the constraint approximation becomes more accurate near the solution, the nonlinear constraint is then satisfied. Figure 5.43 shows the convergence of the Lagrangian gradient norm, with the characteristic quadratic convergence at the end.

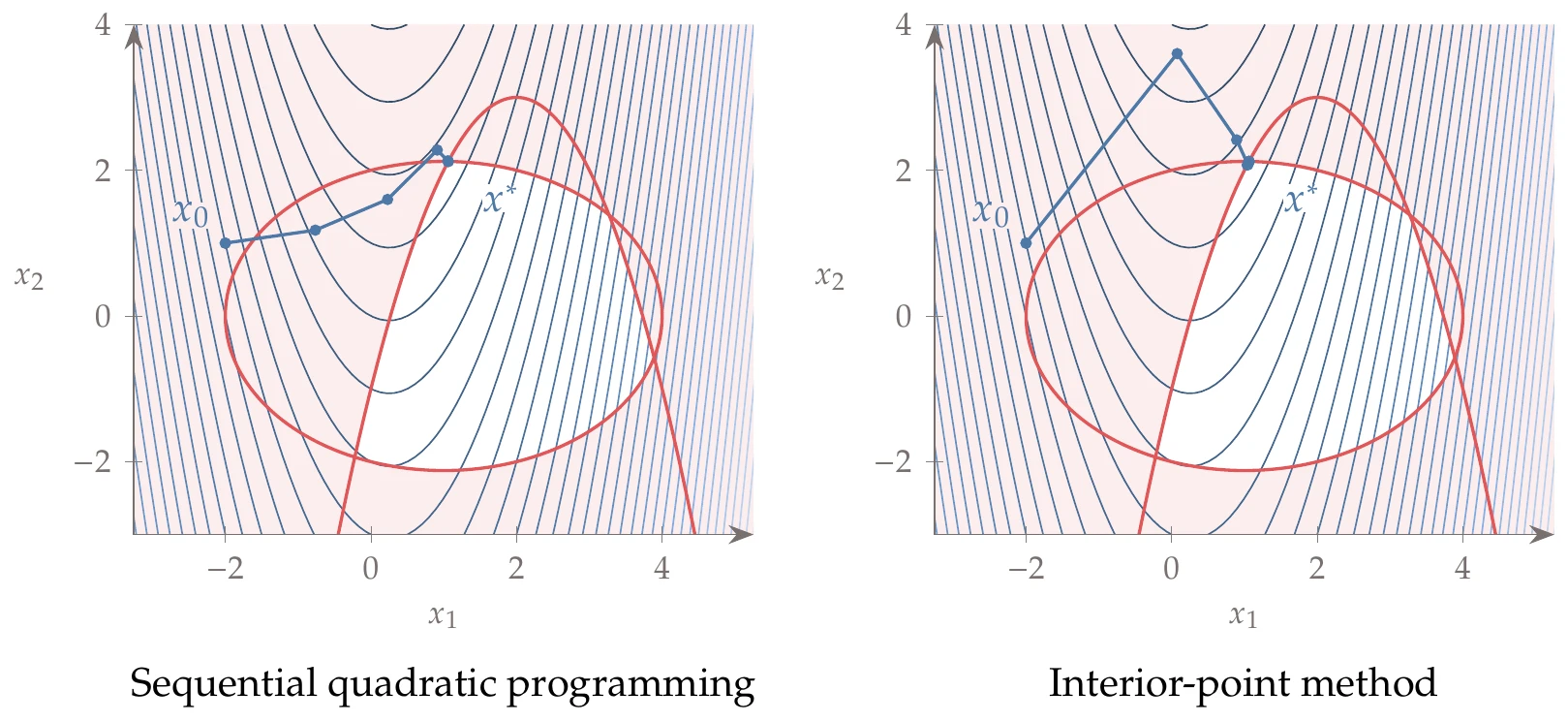

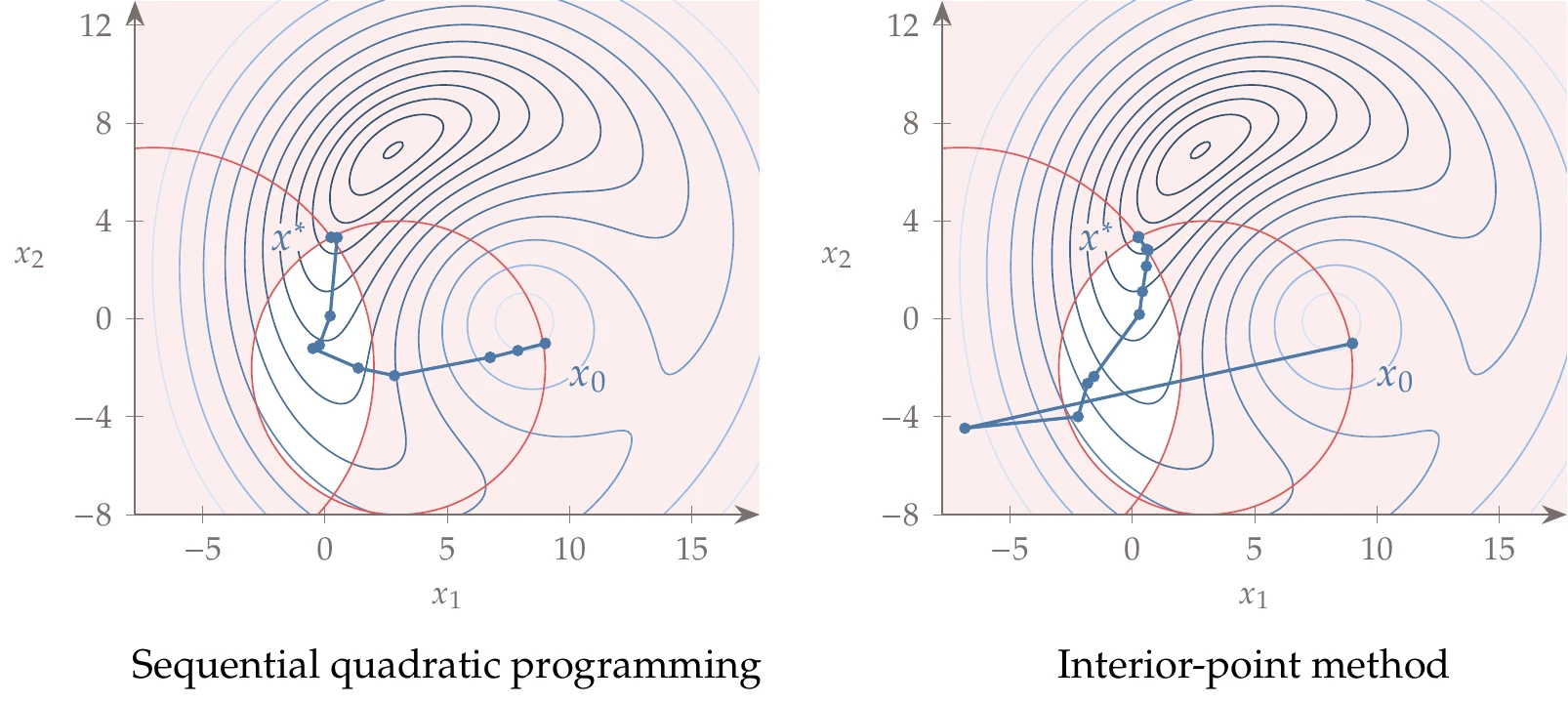

We now solve the inequality constrained version of the previous example (Example 5.4) with the same initial conditions and general approach. The only difference is that rather than solving the linear system of equations Equation 5.62, we have to solve an active-set QP problem at each iteration, as outlined in Algorithm 5.4. The iteration history and convergence of the norm of the Lagrangian gradient are plotted in Figure 5.44 and Figure 5.45, respectively.

Figure 5.44:Iteration history of SQP applied to an inequality constrained problem, with the Lagrangian and the linearized constraint overlaid (with a darker infeasible region).

Figure 5.45:Convergence history of the norm of the Lagrangian gradient.

Constraints that take the maximum or minimum of a set of quantities are often desired. For example, the stress in a structure may be evaluated at many points, and we want to make sure the maximum stress does not exceed a specified yield stress, such that

However, the maximum function is not continuously differentiable (because the maximum can switch elements between iterations), which may cause difficulties when using gradient-based optimization. The constraint aggregation methods from Section 5.7 can enforce such conditions with a smooth function. Nevertheless, it is challenging for an optimizer to find a point that satisfies the KKT conditions because the information is reduced to one constraint.

Instead of taking the maximum, you should consider constraining the stress at all points as follows

Now all constraints are continuously differentiable. The optimizer has constraints instead of 1, but that generally provides more information and makes it easier for the optimizer to satisfy the KKT conditions with more than one Lagrange multiplier. Even though we have added more constraints, an active set method makes this efficient because it considers only the critical constraints.

5.6 Interior-Point Methods¶

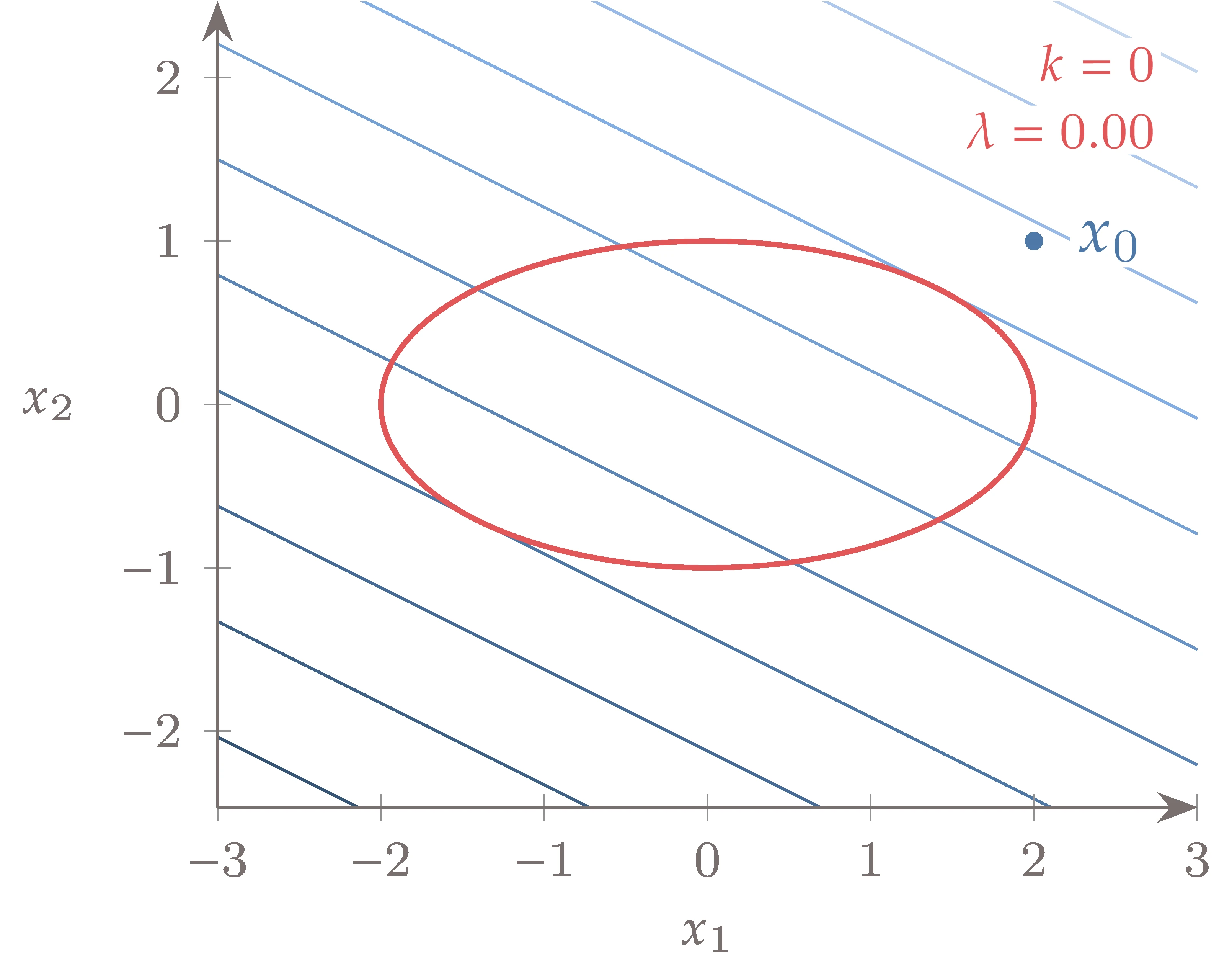

Interior-point methods use concepts from both SQP and interior penalty methods.[19]These methods form an objective similar to the interior penalty but with the key difference that instead of penalizing the constraints directly, they add slack variables to the set of optimization variables and penalize the slack variables. The resulting formulation is as follows:

This formulation turns the inequality constraints into equality constraints and thus avoids the combinatorial problem.

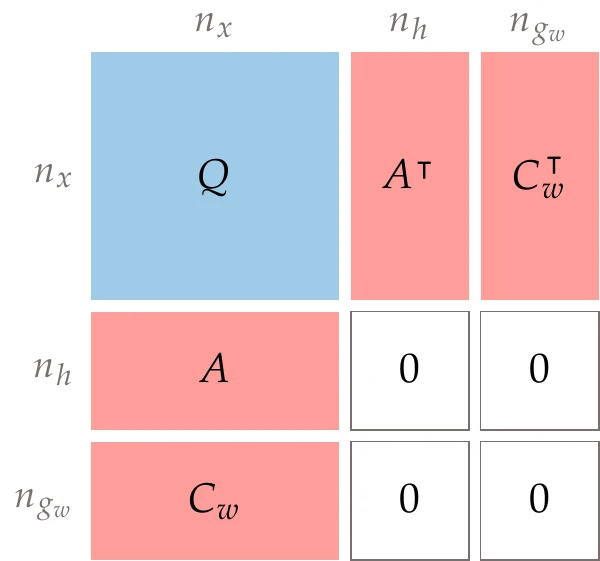

Similar to SQP, we apply Newton’s method to solve for the KKT conditions. However, instead of solving the KKT conditions of the original problem (Equation 5.59), we solve the KKT conditions of the interior-point formulation (Equation 5.95).

These slack variables in Equation 5.95 do not need to be squared, as was done in deriving the KKT conditions, because the logarithm is only defined for positive values and acts as a barrier preventing negative values of (although we need to prevent the line search from producing negative values, as discussed later). Because is always positive, that means that at the solution, which satisfies the inequality constraints.

Like penalty method formulations, the interior-point formulation (Equation 5.95) is only equivalent to the original constrained problem in the limit, as . Thus, as in the penalty methods, we need to solve a sequence of solutions to this problem where approaches zero.

First, we form the Lagrangian for this problem as

where is an -vector whose components are the logarithms of each component of , and is an -vector of 1s introduced to express the sum in vector form. By taking derivatives with respect to , , , and , we derive the KKT conditions for this problem as